The work of Iranian playwright and theater director Payam Laryan has, in recent years, focused on immigration as both a personal and social issue. His reflections are expressed in three plays: Australia (2016), The Inhabitants of Calais (2019), and The Mediterranean (2021). Australia has been performed numerous times by different theater groups. In 2017, it won the thirty-sixth Fadjr Theater Festival prize, and the stage play was published in 2018. The Inhabitants of Calais, the subject of this note, imagines the struggles of the refugees in the historical city of Calais in France. The final play in Laryan’s trilogy, The Mediterranean, addresses the conditions of artists and students during different periods in Iran’s contemporary history. Its fate has been as complex as the circumstances its characters find themselves in. Although it won the Fortieth Fadjr Festival’s prize for best dramaturgy in 2021, the play has only been performed privately in underground venues.

In his introduction to The Mediterranean, Laryan explores immigration from different perspectives, including those of writers forced to leave countries plagued by political issues. For him, these writers find themselves in a double bind. On the one hand, they are welcomed in a new land of hope and work opportunities, while on the other, they find themselves abandoned in a desert of hopelessness. Laryan reveals that he himself faced the dilemma of whether to stay or migrate in his early twenties, eventually deciding that instead of searching for freedom in another country, he would take refuge in another world, namely that of art and literature. We might therefore describe the playwright as an immigrant from the land of reality to the realm of imagination. Laryan concludes that “only your dreams will save you… since as a writer you are now used to living in another world: the world that you yourself have created.”

The Inhabitants of Calais is inspired by Auguste Rodin’s sculpture The Burghers of Calais (1884–89). Laryan’s articulate interweaving of form and content produces a play that is impeccably coherent despite its various intertextual references. The story is inspired by two horrific historical events: one contemporary, the other medieval.

In 1346, King Edward III of England laid siege to Calais, ordering his army to execute all its inhabitants. He later agreed to end the siege under the condition that six prominent citizens surrender to him barefoot, with ropes around their necks, ready to die. Six of the city’s leaders accepted his demands. However, the pregnant English queen, Philippa of Hainault, worried that the executions would cause ill fortune to befall their child, begged the King to spare them. Rodin’s famous sculpture The Burghers of Calais commemorates this event. Instead of depicting the six men as heroes, the sculptor chose to show them in the midst of their anguish, walking toward their presumed deaths. He portrays their psychological struggle as they are separated from their city and fellow citizens. Eight centuries later, Laryan took his inspiration for The Inhabitants of Calais from this sculpture, recounting the story of these six men through the experiences of six refugees caught up in the French government’s siege. At the end of the play, Khadim — or is it Silan? — tells us that “here in Calais, things are always like that. There is no other story.”

On October 26, 2016, French soldiers forcibly cleared the so-called “Calais Jungle,” an encampment of refugees and migrants in Calais, removing its inhabitants to other camps throughout France. Thus, those sheltering near the English Channel in the hopes of immigrating to the United Kingdom were forced to abandon their dreams. Laryan’s play imagines this catastrophic day.

Khadim, a migrant from Rwanda, is the victim of ethno-racial violence. When he was eight years old, the Hutus murdered and mutilated his parents and beloved brother, Endia, during the genocide against the Tutsi. He survived because, at the time of the murders, he was down at the lake fishing and waiting for Endia to join him. At twenty seven, he decided to immigrate, eventually arriving in Calais. Khadim loves to dance. He dreams of going to “the island” and becoming a professional dancer so that he can one day express his suffering in a language common to all humans. To others, Khadim appears to have lost his mind because, to keep the memory of his family alive, he constantly tries to reanimate their mutilated bodies in his own body through dance.

Lavia is Iranian and a victim of domestic violence. Upon discovering that she had been intimate with a man, her brothers, unable to find her lover, decided to kill her. She attempted suicide by self-immolation but was saved. Now Lavia hides the scarred part of her face from others. Before he ran away, her lover told her to meet him in Calais. She is there to find her beloved, carrying just a single photograph of him. He could bear any name, but for her, he has only one face. Lavia neither ages nor dies. For years she has stayed the same. Khadim describes her as the loneliest, saddest song one can sing. In his dreams, Lavia sings while he dances, and they communicate through song and movement. For Khadim, “Lavia is Endia himself.” However, he is not the only one in love with Lavia in the Jungle camp.

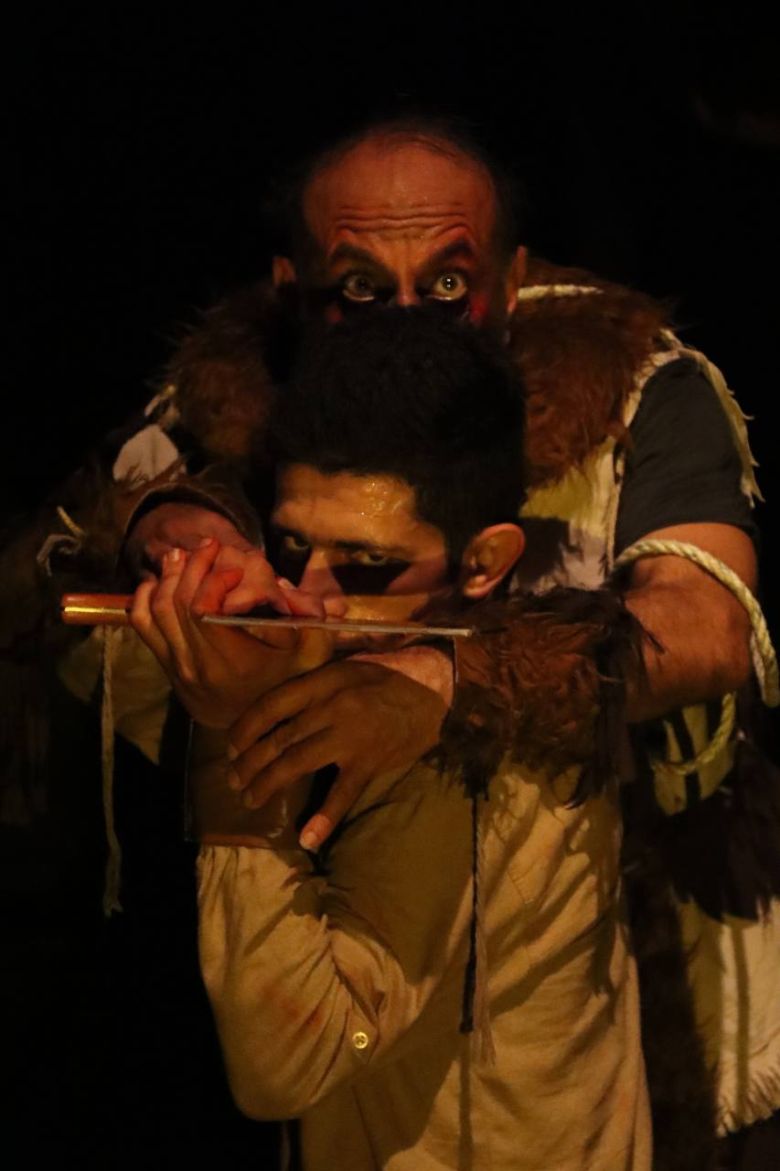

Silan, known as the monster of Calais, is a victim of environmental and economic circumstances. He used to be a mountain porter, or as he says himself, he carried luggage for tourists like a goat in the Indonesian mountains. One day, while working, he witnessed from high up in the mountains a gigantic tsunami hit Palu, devouring his wife and children who were collecting crabs down on the beach. Desperate and not wanting “to be a goat anymore,” he arrived in Calais in a refrigerated container filled with slaughtered pigs. He whispers to himself, “Who could ever understand you, Silan? Who could ever know what it means when the waves reach the sun? Who could know what it is like when the monster comes out of the sea?” Having lost everything to the tsunami monster, Silan himself has become a monster. Other refugees call him names, such as the monster of Calais, the butcher of Calais, or the wolf of Calais: “They say the butcher of Calais does not let anyone see his feet. They say he has the feet of a wolf. … Silan has so many faces.” Now in Calais, he slaughters pigs. He wears boots, and a cleaver hangs from his neck. Because he has been in the Calais Jungle longer than anyone else, Lavia seeks him out to ask whether he has seen her beloved. Silan says to her, “No one here dares speak to me. How come you speak to me?” Lavia replies, “I am Iranian. Do you know what that means?” Her answer appears to have nothing to do with his question, yet it expresses everything there is to say. With it, she implies that as a woman from a harsh patriarchal society, nothing frightens her. She is looking for someone who is not like her brothers, someone who does not hide his true face, someone who keeps his promises. When Silan suggests her beloved may have already gone to England, she replies, “Then it no longer matters. … He was supposed to be here. If he has already left… Then he hasn’t been waiting for anyone.” Lavia is the incarnation of hope, love, and loyalty.

One day, Silan approaches Lavia’s tent, bearing news about her beloved, but Khadim, thinking he intends to rape her, stabs him with a knife. Silan is taken to hospital, and Khadim is imprisoned in a medieval castle in Calais. Silan leaves the hospital and Khadim is released from prison on October 26, 2016, the day of the siege. Amid the chaos, Silan takes his revenge on Khadim by taking his life. As he kills him, Silan, who has many faces, metamorphosizes into a wolf-man and then into his victim. He reaches out to Lavia, who attacks his face. But whose face? Silan’s or Khadim’s? Silan wearing Khadim’s face or visa-versa? But what does it matter? At the beginning of the play, the narrator introduces himself as Khadim. An hour before his murder, he has taken refuge in the Jungle. Concealed by its trees, he tells us his story while knowing he must eventually leave his hiding place and surrender to the French police.

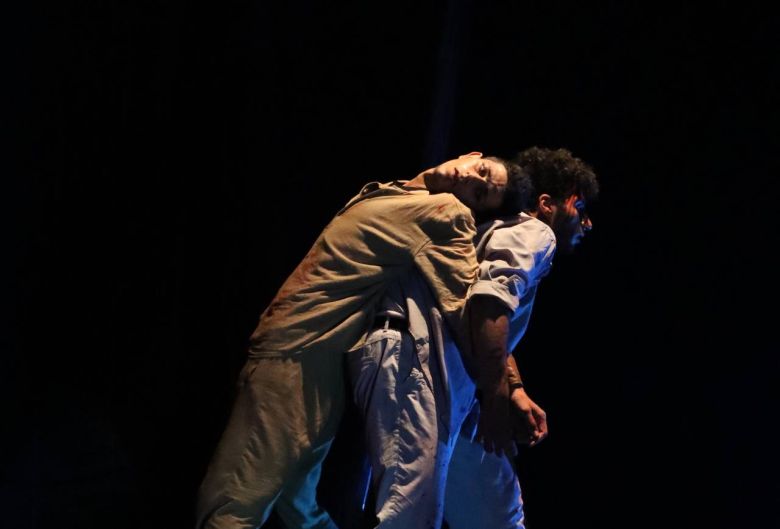

As in Rodin’s sculpture, the number six plays a crucial role in Laryan’s play. The six actors sometimes appear as Khadim, sometimes as Silan, and sometimes as Lavia’s brothers. Each of the six actors who play Khadim represents a different period in his life, underlining the purgatory he finds himself in and contributing to the surreal, nightmarish atmosphere of the play. At various points, the line, “I am not here, I am there,” is said by each of the six actors, an assertion immediately negated by another version of Khadim. As each persona refers to the next by affirming they are “not here” but “there,” the chain of self-dispossession continues without the audience ever seeing the “there” they all claim to inhabit. The location of “there” is entirely in the hands of the new gods of our times: the nation-state and its police force. Khadim tells us, “I have nothing left but a channel on the other side of which they say lies paradise.” And yet, he does not know what awaits him at the other end of this tunnel to paradise.

Caught in the vise of suffering, experienced first in their homelands, then on their migrant journeys, and now here in the purgatory of the Calais Jungle, and gripped by doubts about the future homes that await them, these refugees, their identities shattered or utterly destroyed, are unrecognizable to themselves. Khadim, Silan, and Lavia are obsessed with the idea of having only one face: a human one. However, like the characters in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, they are constantly changing shape. They exist somewhere between human and animal, like centaurs, or between human and plant — leaf-like, blown by the wind, attached to nothing. Like Daphne, transformed into a laurel while escaping Apollo, Khadim turns into a tree to hide from the police, the armed gods of today, seeking to enroot himself finally, even if in purgatory. Silan, the hardworking Indonesian who first introduces himself as a goat-man, does not want to live the life of a human animal anymore. However, in the purgatory of Calais, he is reduced to a cleaver-man, recognizing himself solely in this object: “The cleaver is part of my hand, it can’t be detached from it.” While rushing to kill Khadim, overcome with fury, his skin thickens and his hair and nails grow as he metamorphosizes into a wolf. The conditions of his life have transformed Silan into the wolf-man of Thomas Hobbes’s famous dictum, homo homini lupus (man is a wolf to man).

Payam Laryan believed in the imagination as a way of making real life tolerable and tried to impart this message to his audiences. However, reality is ultimately more stubborn than human will and determination. Reality crawls its way into the world of imagination, producing the nightmares that weigh down the soul and the world. The Inhabitants of Calais is one such nightmare, experienced by all those who inhabit purgatory’s torments.

Translated by Golnar Narimani

Natasha Moharramzadeh, “The Inhabitants of Purgatory: A Review of the Inhabitants of Calais by Payam Laryan,” in mohit.art NOTES #11 (June/July 2024); published on www.mohit.art, May 31, 2024.