Modern theater in Iran can be seen as a legacy of the Enghelāb-e Mashrūteh, the Constitutional Revolution, which took place between 1905 and 1911. Although the Constitutional Movement did not bring about immediate political change, the discourse around it opened up exciting cultural vistas for the Iranian people.1 Various journals reflected progressive, independent ideas. Intellectuals organized non-government affiliated schools to replace the traditional ‘maktabs’, and theater courses were held outside school hours. Within the country’s restricted and autocratic atmosphere, theater became a bearer of critical and alternative ideas.

Political relations between Iran and Russia played a role in the flourishing of Iranian theater. Following two imposed wars during the Qajar period, the South Caucasus region, roughly corresponding to Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan today, was separated from Iran and became subject to Russian economic and cultural policies. Thus, this region was gradually integrated into Russian culture, bringing modern theater from Moscow and Saint Petersburg to the Caucasus region. Various theater troupes were formed, including itinerant ones. Iran was a significant destination for these traveling groups, who economically benefited from performing in Rasht, Anzali, Tabriz, and Tehran. The Caucasus region was a hotbed of social democratic theories, and these performances were also an occasion to introduce new political ideas to audiences living through a turbulent time in Iran’s history.

Russian theater’s inclusion of music and its passion for operettas and operas was brought to Rasht and Anzali by these itinerant troupes. In Rasht, Ahmad Derakhshan, a leading figure in Gilan theater, performed works by Azerbaijani composer and musicologist Uzeyir Hajibeyov (1885–1948) and his brother Zulfiqar, using modern orchestrations of traditional Azeri melodies, which found a highly sympathetic audience among the people of Gilan.

The first compulsory migration of Armenian people to Iran, was carried out by Abbas the Great, the Safavid shah of Iran from 1588 to 1629, under brutal circumstances. The Armenians, a powerful and prosperous people, were forced by Qizilbash soldiers through the raging Aras River, with no access to boats or bridges, toward Iran. After arriving at Tabriz, they moved on to Gilan, Mazandaran, Qazvin, and Isfahan. From the Safavid period through to the Qajar era, Armenians, who were major dealers in sericulture, gradually established their own cultural position in the region. It can be imagined that Armenians in Iran faced many difficulties due to religious differences. However, with the passage of time and through a strong economic and creative presence in their host society, Armenians were able to construct their own churches and oversee the religious, educational, and administrative affairs of their community.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, Tsarist policies in the Russian Empire triggered conflicts between Muslims and Armenians, causing an exodus of Armenians. Many immigrated to Gilan, a green province in northwest Iran, which lies along the Caspian Sea. These migrants, more exposed to science and politics than previous generations, were mainly doctors, dentists, engineers, or merchants. Their presence played a significant role in the economic and cultural strength of the region and its vibrant cities, including Rasht and Anzali. They also contributed to the development of Gilan’s art and culture, especially theater. Armenian and Azari artists helped Caucasus school theater flourish in the region, where its influence was reinforced by deep cultural-historical ties. Uzeyir Hajibeyov drew on Iranian themes for many of his operas, including Rostam and Sohrab, Leili and Majnoon, and Shah Abbas and Khurshid Bano, while Azerbaijani poet and satirist Mirza Ali Akbar Khan Saber (1862–1912) wrote poems for the Iranian constitutional movement.

In 1883, Hovhannes Dowlat Beigian, an Armenian immigrant from Tbilisi, was hospitalized in Rasht. After his recovery, he was invited to stay in the city and teach at the Armenian School of Rasht. When he learned about the school’s financial problems, he decided to help by putting on two plays. On January 28, 1884, with the cooperation of students and the church choir, he staged We Are Both Poor and Khetcho’s Winner Card in Armenian. Two other plays followed on February 14. The performances were warmly received and all proceeds went to the school. In 1887, another Tbilisi teacher established the Book Lovers and Theater Lovers associations.

Rasht was an important center of Iranian commerce with Caucasus and Russia. The city was host to different ethnic groups and political ideas, creating an environment that encouraged inclusion and integration. Its provincial parliament was comprised of a diverse range of politicians, from the religious Mujtahids to the Armenian Social Democrats. In this atmosphere, Iran’s first theater hall was established in Rasht.

Avadis Hordananian, a silk merchant in Rasht, built a school and theater complex dedicated to his son, Meguertitch, whom he had lost to an illness. Its theater hall, the first European style auditorium to be built in Gilan, had a capacity of around one hundred and eighty seats. Avadis Hall opened its doors in 1905 and served all the citizens regardless of ethnicities and religions. For decades, the hall was a central pillar of the community, playing an important role in bringing together people from different ethnic, religious, and historical backgrounds.

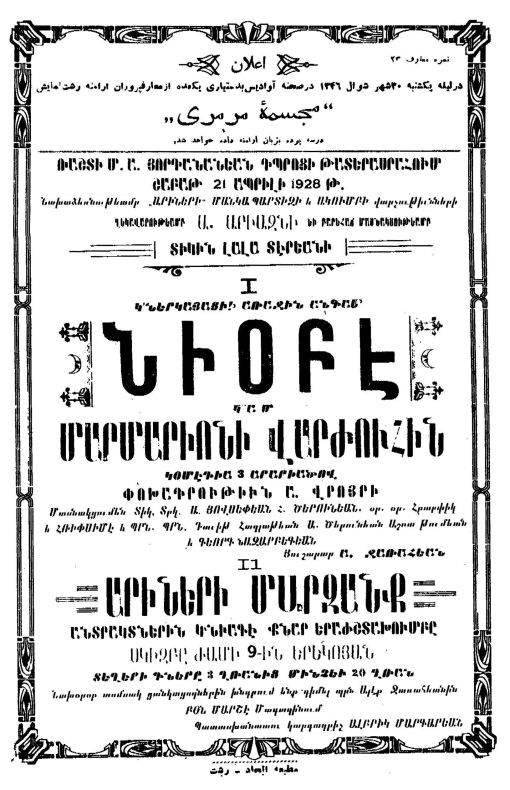

Little information exists today about the performances that took place at Avadis Hall. According to surviving posters, we know that along with translated stagings of plays by Western playwrights, including Shakespeare, Henrik Ibsen, Molière, and Anton Chekhov, plays by Iranian and Armenian writers, such as Gregor Yaghikian (1880–1951) and Reza Kamal (1898 –1937) were also performed. Kamal, known by the pseudonym Shahrzad or Scheherazade, was an Iranian poet and playwright who wrote significant roles for women. Professional theater groups from Tehran and Tabriz also performed at Avadis Hall.

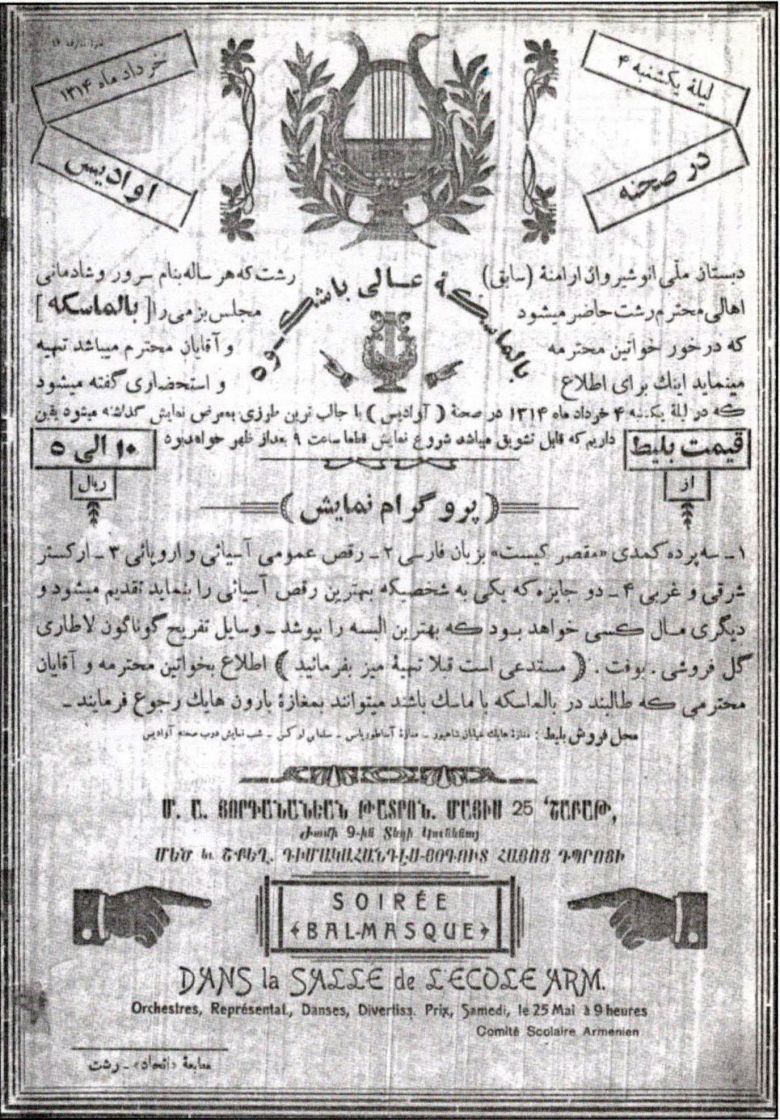

Many of the performances were in the service of charity events. At the time, inspired by the Constitutional Revolution, many cultural organizations were forming who also supported oppressed people. The Armenians in turn established two initiatives: The Rasht Armenian Theater Lovers and the Rasht Armenian Charity. Their colorful performances to raise money for schools, hospitals, and charities are a testament to the unity and sympathy of the citizens, regardless of ethnicity or religion.

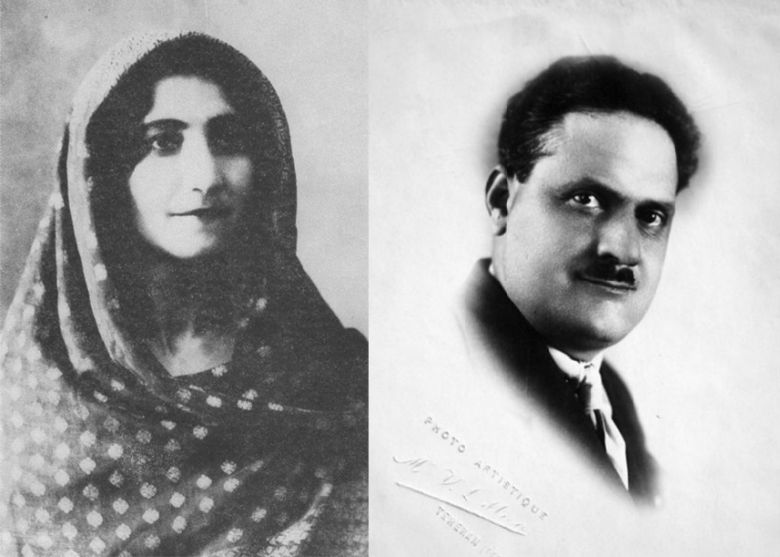

Armenian women made significant contributions to the development of art and culture in Gilan. Manooshak Sanasarian, who was fluent in Azari, Russian, English, and Gilak, married Arsham Sanasarian, an Armenian intellectual who was also an actor. In 1916, Manooshak Sanasarian joined the Association of Theater Lovers, and in 1923, she established the Women’s Theatrical Group to train women in acting and stagecraft. Up until then, female roles had been played by male actors, while male roles had been played by female actors in private shows that only women could attend. Thanks to the efforts of Manooshak Sanasarian and the Women’s Theatrical Group, women gradually stepped onto the stage and performed together with men.

In Tehran, two leading Armenian-Iranian actresses left an indelible mark on Iranian theater. Satenig Aghababian (1900–1979) was an actress and opera singer who had studied in Berlin, Moscow, Rome, and Paris. She returned to Iran in 1920 and performed extensively until 1940. Varto Terian (1896–1974), also known as Madam LaLa, was born in Tabriz and studied in Switzerland. As Iran’s first theater actress, she became famous for her performances in the plays of Shahrzad. Terian and her husband, Arto Terian, a theater actor and director, performed extensively as a duo. All the three actors traveled to Gilan, and their performances at Avadis Hall in the 1920s and 1930s fascinated theater lovers.

Let us now look at three historical scenes that took place at Avadis Hall.

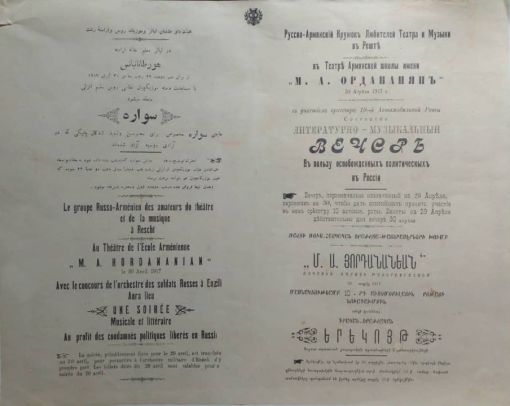

It is 1915, one year after the start of World War I. Tehran is occupied by Russia and the United Kingdom, and Gilan is occupied by Russia, under the ominous shadow of Ovseenko, the Russian Consul General. In the meantime, patriot Mirza Kuchik Khan (1880–1921), an Iranian twentieth-century revolutionary leader and president of the Gilan Socialist Soviet Republic, has arrived in the region, intent on waging guerrilla warfare against the occupiers. Against such a backdrop, on January 31, a magnificent evening performance is put on at Avadis Hall by the Volunteer Committee of Russian and Armenian Literary Music and Theater in Rasht with Ovseenko’s support.

According to the program, a scene from the opera Faust followed by Chekov’s play The Bear are performed to a packed house of high-level Russian officers and their Iranian accomplices. As a result, the performance takes place behind closed doors, with no press coverage, and the people of Rasht, including the Armenians, the main owners of the hall, are shut out. Oddly, the program begins with the national anthems of Russia, the United Kingdom, and France. The host country’s national anthem is not played until the second half of the program, following the intermission.

With the departure of the occupiers, Gilan enters a new chapter, as does Avadis Hall. As an example of multinational collaboration, on May 20, 1917, an open-air evening concert and dance program is performed by Russian, Iranian, and Greek actors. Included among their ranks are translators, writers, intellectuals, and other professionals. All proceeds from this performance go to the theater itself.

From 1920, Iranian society moves toward relative stability and security, and modernization policies accelerate. In Gilan, Avadis Hall earns a special place among the newly emerging theater groups due to its modern performance space.

Theater’s vibrant atmosphere of sympathy and loyalty absorbs many young people. Among them is Jahangir Sartip-Pour (1903–1992), an essayist and songwriter who will go on to serve as Rasht’s mayor and a member of national parliment. Sartip-Pour is inspired by Gregor Yaghikian and translates two of his plays.

Three army doctors approach Sartip-Pour to ask for his assistance in establishing a hospital. He writes the play The Grave Consequence, and enlists the help of the Rasht Culture Community Theater Society. Mirza Mohammad Hossein Khan Dayi Tabrizi (1870–1925), known as Daiy Namayeshi (Namayesh Means theater in Persian), who is an actor, theater director, and philanthropist is chosen as director. Daiy Namayeshi is cofounder of the Hey’at Omid Tarraghi (Association of Hope for Progress), the first theater association in Iran. The managers of Avadis Hall cooperate, and tickets are printed for free. During the interval, the performers talk to the audience about the purpose of the project and ask for donations toward necessary supplies for the medical center. The play raises a considerable amount of money, and a house is rented. This becomes a clinic, and eventually, other charity organizations in Rasht contribute to the building of a hospital.

Avadis Hall, a shelter for Gilan theater artists and itinerant troupes from Tehran and the Caucasus region, is a successful example of solidarity between immigrants and hosts in Iran. Over time, by preserving their identity and rights, the Armenians of Gilan became part of the province’s cultural fabric, and they rarely considered themselves immigrants. Gilani people used to call Armenians “Armeni Brar” (Armenian brother). The city of Rasht was completely shut down on only two occasions, both times for the large funerals of two immigrants: Dai Nameishi and Arsen Minassian (1906–1977), an Armenian-Iranian scientist, and the inventor of Gilan’s sanatorium. Unfortunately, most Armenians in the region migrated from Iran following the Revolution of 1979.

Translated by Helia Darabi

1 The history of theater in Iran goes back to antiquity and includes ceremonial plays glorifying national heroes and legends. Various forms of dramatic performance were also prevalent throughout the centuries, including Ghāvāli (minstrelsy), Shahnameh-khāni (singing performance of the story of Shahnameh), Sāye-bāzi (shadow plays), Mirnouroozi (comic play during Nowruz), Ta’ziyeh (tragedy in the Shiite world), and various forms of marionette plays.

Faramarz Talebi, “Fragmented Images: The Role of Armenian Immigrants in Gilan Theater,” in mohit.art NOTES #11 (June/July 2024); published on www.mohit.art, May 31, 2024.