To live despite one’s fate finds a familiar echo in the ancient struggles between men and men, humans and gods in the polis. Greek tragedies tell us about this singular way of life, a transforming life: A person departures from living a life of necessity due to disaster, pauses briefly to reflect on the order of these necessities, and finally, wreaks havoc on them through death or a lethal action.

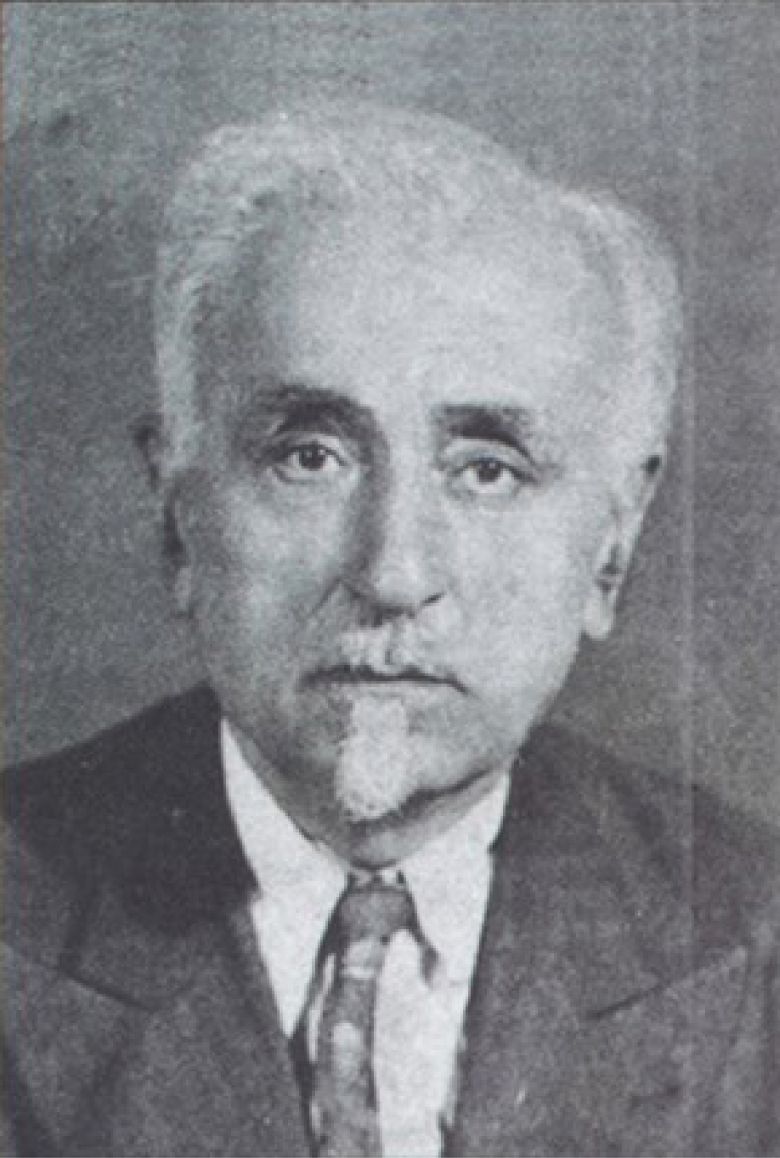

Theater has shown us the ordeals humans face, the fight between good and good, and the demands of circumstance that push an individual to the heart of such a fight. Theater has told us about the freedom to choose between two goods despite one’s fate, and about the complexity of such a choice in order to make humans and society better. The life of Gregory Yeghikian (1880–1951), an Armenian migrant in Iran, can be remembered as a life lived, despite destiny, with the dream of reaching freedom in its most expansive sense, that is, freedom from constraint, domination, or coercion.

The Ottoman rule over the Armenians and the great suffering it caused forced Yeghikian to leave his birthplace. But he never stopped dreaming of Armenian liberation from the Ottomans and for his people to be able to return to their homeland. He traveled to Russia, Europe, the United States, Iran, Tbilisi, and Baku before finally choosing Iran as his second homeland. However, this new homeland was not free either. Hence, this migrant’s entire life can be summarized as a fight for freedom, sustained through his various roles in Iran as a translator, political activist, journalist, teacher, playwright, theater director, and actor. In his struggle, Yeghikian always talked about “us,” addressing both his Armenian and Iranian identities. He wrote as much about “we, the Armenians,” as about “we, the Iranians.” Yeghikian’s political activism and his impact on a particular period of Iran’s contemporary history through the Jungle Movement have made him a controversial figure, yet his remarkable impact on Iranian theater and dramatic arts is indisputable.

Yeghikian’s profound love for both his homelands and his passionate desire to create a nation resonate in the words and expressions he coined and repeatedly used. Mellat-parvari (nation-nurturing) and Vatan-parvari (homeland-nurturing) are recurrent terms created by the playwright that differ from nation-building and patriotism. For Yeghikian, these compound words stress the duty of intellectuals to nurture their homeland and people. They tell us about how Iran became his motherland and how he took it upon himself to foster it, rear it, and raise it as if it were his own child.1 He believed that to foster a nation, first we need schools, then newspapers, and then theater. His preference for tragedy was neither an aesthetic choice nor a question of entertainment but deeply rooted in his own life and situatedness: the situation of an Armenian migrant who had chosen another country, Iran, as his second home; the situation of one forced to live on the edges of geographical, linguistic, religious, and ethnic borders, who experienced the gnawing of external antagonisms and internal paradoxes — all while sharing a common fate of marginalization with both Iranians and Armenians.

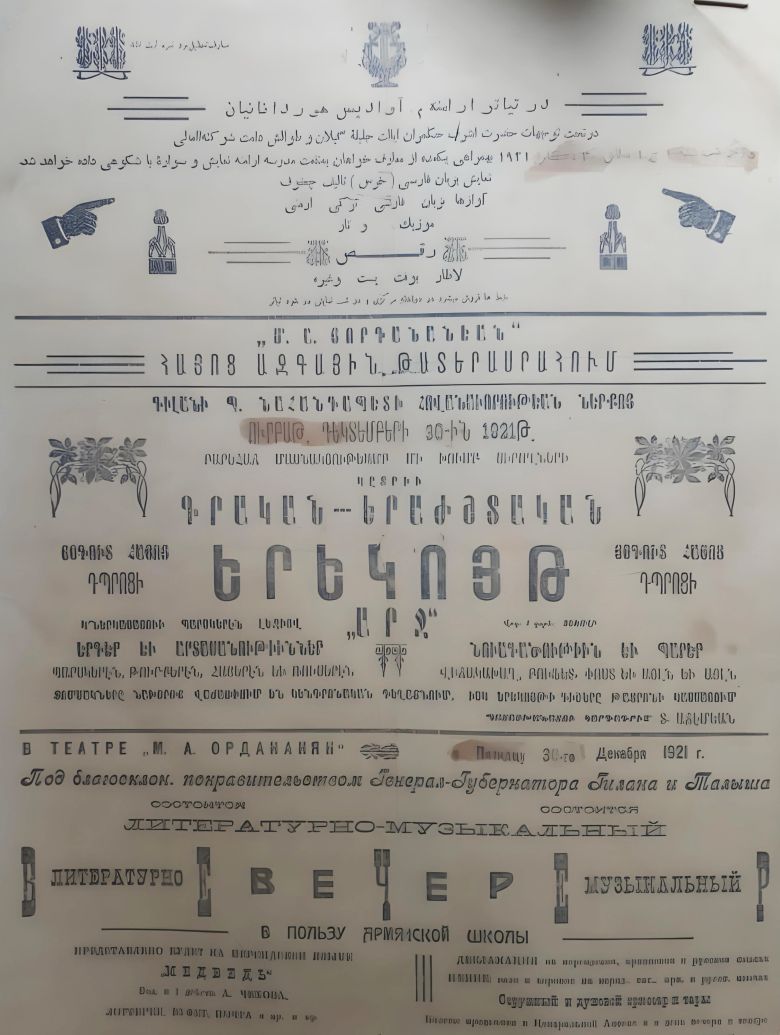

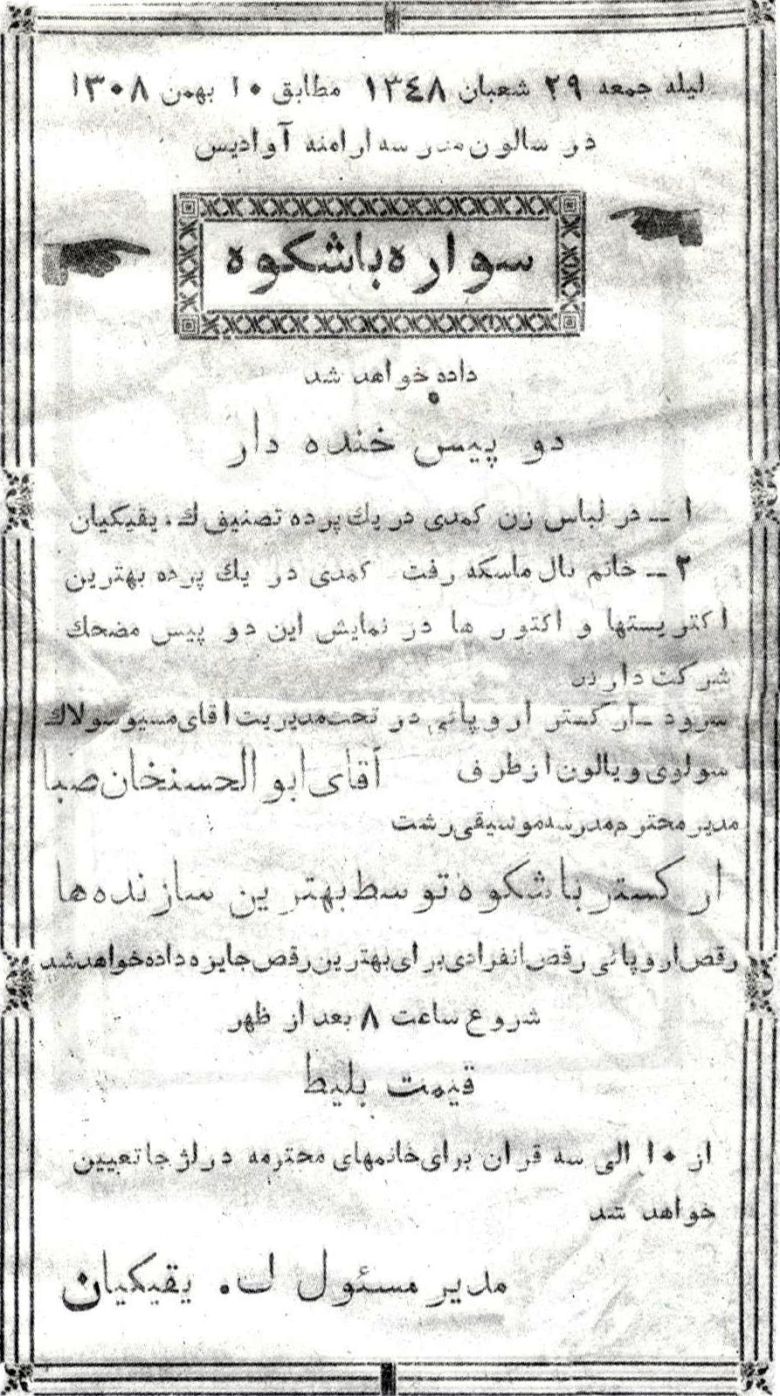

Produced in the midst of so many fissures, Yeghikian’s oeuvre masterfully engages with an extensive range of contemporaneous debates and antagonisms, including the clash between East and West, communism, patriarchy, democracy, despotism, modernization, war, colonialism, love. But above all, he wrote about women. Yeghikian crafted four plays during the first decades of the twentieth century, which were performed in theaters across Iran, mostly in Gilan. These plays provide us with a clear image of this Armenian migrant with two homelands.2

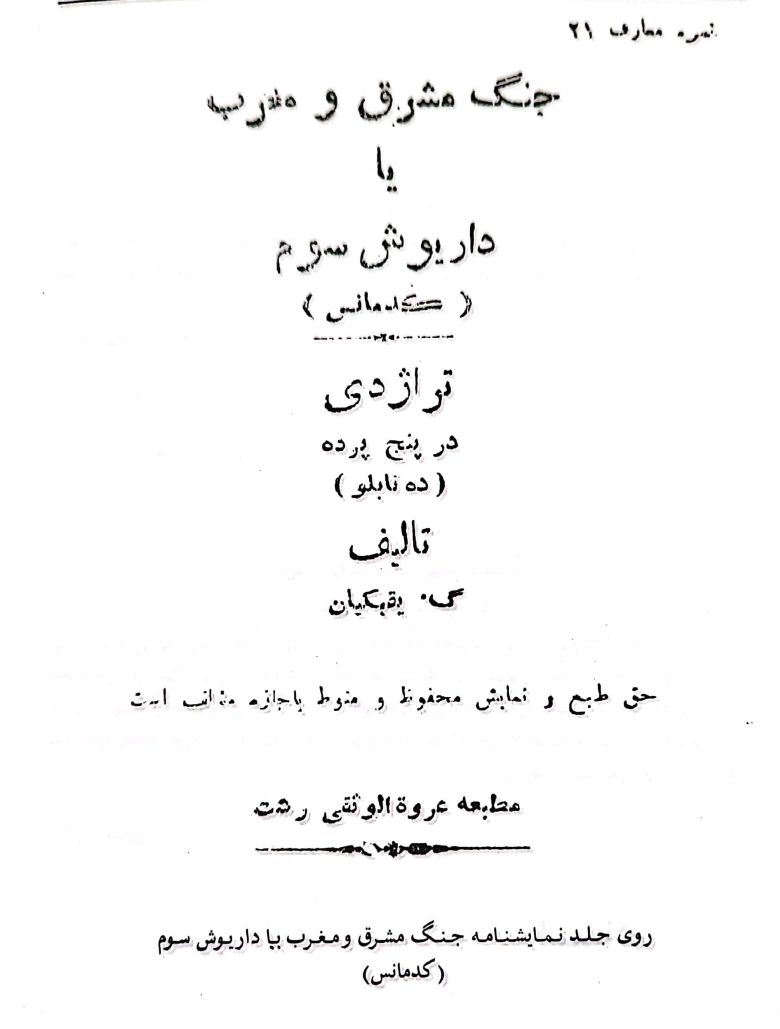

Yeghikian’s “we” shows his firm belief in a shared destiny. A “we” sometimes manifested in his distinction between “us,” the East, as opposed to the West, and sometimes in his distinction between “us,” the Nationalists, as opposed to the Internationalists. In his play The War of West and East or Darius the Third (c. 1920s), Alexander invades Darius’s land while the king drowns himself in debauchery and his inept courtiers conspire against him. Despite the efforts of Homāy, Darius’s wise daughter, Ariobārzān, and the chief Mowbed to save Iran, Darius is defeated. His death brings victory for Alexander. In the tragedy, the glory, charisma, and dignity of the East and Iran are extolled. The playwright speaks of an “Iranian spirit” that will survive and continue to thrive despite Alexander’s occupation of Iran. A spirit that will one day rise again since “the East cannot surrender to the orders of the West.” Nevertheless, Yeghikian does not depict the conflict between East and West as one between light and darkness, but rather as a conflict between two lights, as the chief Mowbed, addressing Darius, proclaims: “Ariobārzān, like the prophet of new truths, is confronting the other side of this new truth, that is Alexander.”

Yeghikian’s growing nationalism increasingly distanced him from revolutionary ideas and internationalism. This nationalism is most evident in his play The Just Anushirvān and Mazdak (c.1920s). Mazdak, a new prophet with a new religion, questions and destabilizes the social order, provoking the poor to rebel against the upper classes. The just Anushirvān, joined by the Moobads and his mother, Mehrnoush, suppresses the uprising, executes Mazdak, and reunites the country. The play reflects Yeghikian’s skepticism toward the paradise promised by communism.3 In such a paradise, Mazdak would “carry the light of Ahurāmazdā and would be the prophet of peace and equality” and “the preacher of freedom and liberty.” Instead, while the masses are being tortured and killed, Mazdak amuses himself at the royal court of King Qobad, the Sassanid king, preferring his company to the respect of the farmers. Finally, after much bloodshed, Mazdak leaves us with the unanswered question: “What good did it all have for the freedom of humanity?” Yeghikian’s nationalism as a refugee is vastly different from the nationalism of Reza Shah, founder of the Pahlavi dynasty, and his nation-building project.4 The aim of Shah’s nationalism was to purge the country of ethnic, linguistic, and cultural diversity so that all Iranians would speak one language and dress identically. Yeghikian’s nationalism, on the other hand, sought a unified Iran in all its plurality. He believed plurality was the foundation of democracy, an idea indebted to his identity as a migrant from an Armenian minority.

Freedom, for Yeghikian, is related to an individual’s self-determination and autonomy. His play Who is right? (c. 1920s) addresses poverty, choice, and misogyny. Kamal plans to marry his daughter — a young woman who admires knowledge and education and is eager to continue her studies — to a married man with children in exchange for money her father owes him. The essence of the tragedy is pronounced in the play’s title, as all the characters seem to be in some way right. Yeghikian demonstrates how, instead of focusing on an individual’s actions, we should redirect our attention to the conditions that leave individuals with no choice. The pressure of Kamal’s circumstances forces him to make a necessary choice, despite wanting the best for his family, despite sending his daughter to school against the customs of his time, asking her opinion of the marriage, and not wanting to treat her “like a handmaiden.” The pressure of Forouzan’s circumstances forces her to choose whether to continue her studies and become an educated woman or be sold “like an animal.” Initially, she resists the marriage but, in the end, decides to sacrifice her life. Kamal eventually dies from the anguish of the choices both him and his daughter were forced to make and his love for her.

Independence and equality for women, freedom of choice, and peace are the main themes of Yeghikian’s play The Horror Square (c. 1920s). Jamileh, a nurse, has survived a horrendous war. Forswearing her love for Sohrab, the chief commandant at the frontlines in Shiraz, she agrees to marry another man. Sohrab, who turns out to be the cousin of Jamileh’s new husband, Bahador, returns from the war, wounded and disabled. Finding the situation intolerable, he eventually commits suicide. The words spoken by Sohrab give voice to the playwright’s hatred of war and his dream for a better world: “This world will certainly collapse, and from its ashes will rise a new world. A world where the soul of war is dead and the bird of peace flies forever in its sky.”5 The character of Sohrab is perhaps a conduit for the dreams of Yeghikian, who experienced many wars in his lifetime and became an everlasting refugee in constant migration.

The tussle between free will and fate, which lies at the heart of tragedy, is interwoven in Yeghikian’s courageous female characters. His image of women is thoroughly progressive for its time. Jamileh is an independent modern figure, an active agent in both her social and private lives, who chooses freely in theory and in practice. She is an educated woman who participates in the war, falls in love, gets married, and when events take a tragic turn that brings her roles into conflict with one another, chooses to love courageously. All this despite knowing that love is not the solution to her pain. “Has love been a solution to any of my anxieties?” she asks herself, reflecting on the complexity of her situation through this existential question.

Yeghikian’s plays reveal the convergent and divergent forces boiling within the heart of this migrant with two homelands, overwhelming his soul with paradoxes while motivating his life despite his fate. His disdain for the UNITY OF ISLAM COMMITTEE, together with his contempt for the Ottoman Empire and avoidance of Bolshevik Internationalism due to his Armenian heritage, brought him close to Great Britain6 despite having been a leftist revolutionary who was well aware of British colonialism. And yet, as an Iranophile migrant from the East, there remained in him a desire to position himself against the West and to speak about Iran’s glory. Notwithstanding the improbabilities, Yeghikian found a shared destiny with Iran, a Muslim country, as a Christian Armenian. In his new homeland, Yeghikian wrote progressive plays in a language he never completely mastered. At a time when society deprived them of any rights and girls’ schools were not tolerated, women were his main protagonists and the driving force of his plays.

Robert Safarian, himself an Armenian with two homelands, presents us with a crucial question in his book Dweller of Two Cultures7: What should a migrant do? Participate in the affairs of their new county or abstain? This question reminds us, above all, of our common fate, our shared destiny. Perhaps today, when borders are more defined and stricter than ever, when nation-states make decisions for their citizens regardless of their opinions, and when the variety of migrants living in Iran is fast disappearing, it seems strange to talk about a common fate, but its necessity and urgency is beyond doubt. For migrants, it is not only geographic borders that change; their emotional and intellectual borders change also, forcing them to define and redefine new ones. And it is exactly these experiences that render a migrant’s engagement with their new situation necessary. One who is able to defamiliarize things empowers the host society by respecting liberty, freedom of choice, cohabitation, and a shared fate, and will work to safeguard these ideals from the violence that borders impose.

Translated by Golnar Narimani

1 Mohammad Hossein Khosrowpanah, Gregory Yeghikian, 2nd edition (Tehran: Shirazeh Publishers, 2021), 593-94.

2 Gregory Yeghikian, Zendegi va Asar e Namayeshi e Gregory Yeghikian [The life and dramatic works of Gregory Yeghikian], ed. Faramarz Talebi (Tehran: Anosheh Publishers, 1999).

3 Yeghikian was a social democrat who did not believe in revolution and violence. Instead, he believed in the gradual transformation of society through economic and social reforms and considered the role of culture important in this process. See Khosrowpanah, Gregory Yeghikian, 16 and 32.

4 Khosrowpanah, Gregory Yeghikian.

5 Homa is a mythical bird in Iranian legends, symbolizing prosperity and good fortune.

6 Yeghikian believed the presence of Great Britain in Iran would weaken both the Ottomans and Bolsheviks. It is important to note that Yeghikian hated the Ottomans because of the suffering they caused the Armenians, and he did not agree with the internationalist policy of the Bolsheviks.

7 Robert Safarian, Saken e Do Farhang [Dwellers of two cultures: The Armenian diaspora in Iran] (Tehran: Markaz Publishers, 2000).

Sima Hassandokht Firooz, “To Adopt Another Homeland: The Plays of Gregory Yeghikian,” in mohit.art NOTES #11 (June/July 2024); published on www.mohit.art, May 31, 2024.