Initiated in 2009 as an open and participatory platform, Persbook continues to run its Annual of Contemporary Art events in cities across Iran. Even the challenges posed by COVID-19 did not deter the continuation of this annual event. From the very beginning, Persbook has fostered collaborations with numerous artists, critics, and researchers on an annual basis, serving as a platform for the introduction and support of many young and emerging artists. Persbook’s founder Neda Darzi describes its objectives as follows: “To create a welcoming and unbiased platform for young and emerging Iranian artists, nurture and support creative talent, raise awareness of humanity’s impact on the planet through presenting diverse forms of environmental art, highlight water scarcity issues, especially in Iran and the Middle East, promote artists as civil and environmental activists, bridge the gap between artists and society, preserve Iran’s rich cultural heritage across different regions, explore marginal symbols and narratives, and contribute to the development of Iran’s contemporary art archive.”1

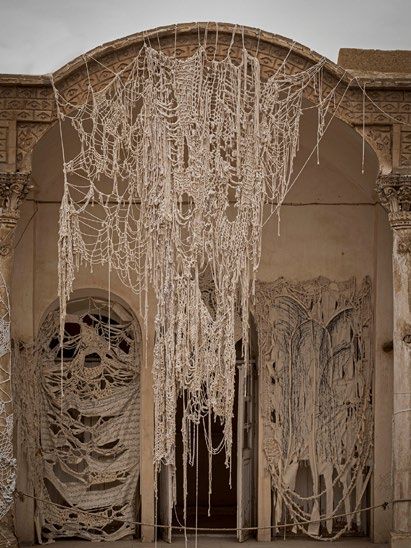

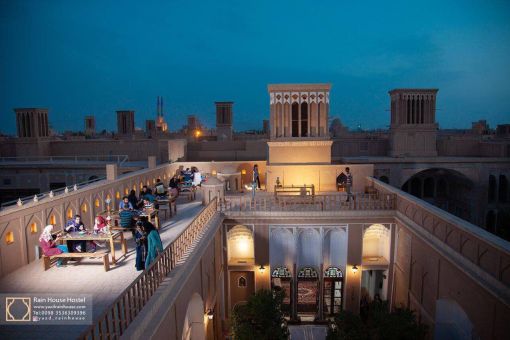

The name “Persbook,” formed from “Pers” (an abbreviation of “Persian”) and “book,” is a play on “Facebook,” the social media platform through which the event was initiated and promoted for a few years. As art historian Pamela Karimi observes in her recent volume on Iranian contemporary art,2 the reason for using the platform was more than just its popularity. Following the Iranian Green Movement of 2009, Facebook was used to showcase many images of violence. Persbook’s goal was to turn this popular social media platform into a place where a collective spirit could be set in motion to heal communities through the sharing of more optimistic images and ideas. Between 2010 and 2016, all selected Persbook works were showcased online and occasionally in a few galleries in Tehran. Since 2016, the artworks have been displayed in remote areas, such as the deserts in eastern Iran or the forests in the north.

The event, initially more intuitive and improvisational, evolved over time, becoming more structured. As Darzi states, “Its focus is on educational rather than commercial aspects, concentrating on gatherings, talks, and workshops, especially in local communities.”3 Over time, independent curators were invited to collaborate, and the event’s venues expanded from Tehran to other cities in Iran. With this gradual evolution, environmental concerns gained prominence, ultimately becoming Persbook’s primary focus. This was a timely positioning. As Iran’s ecological conditions continued to deteriorate due to reckless government policies, a growing awareness of environmental concerns began to emerge in publications, universities, and art spaces. As a result, artists increasingly turned to these issues.

Around this new environmental focus, a critical examination of what it was producing also began to form: “When presented with environmentally conscious art, we find ourselves pondering how these works break free from the familiar narrative of nostalgia for an idyllic past, instead, paving the way for broader questions. These questions include understanding the transformation of ecological conditions due to government policies, exploring the connection between cultural factors and environmental degradation, and delving into the role of philosophy and worldview in shaping human interactions with nature.”4 While Persbook was not the first ecological art event in Iran, it has managed to distinguish itself by incorporating diverse voices and viewpoints, resulting in an event with unique versatility and broad scope.

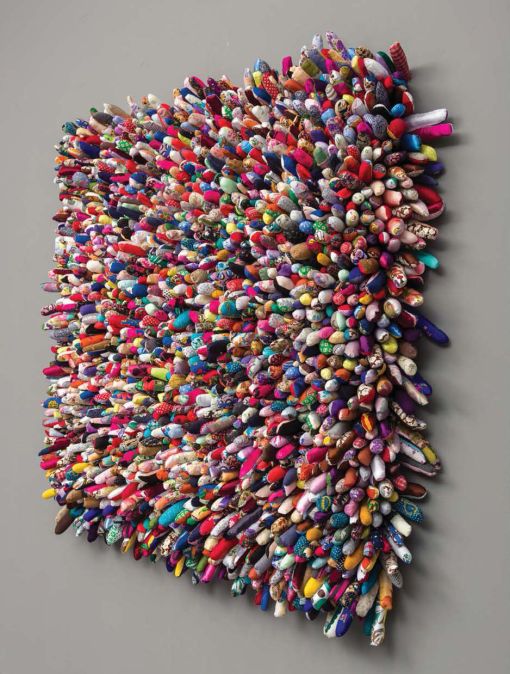

The increasing prominence of women artists with environmental concerns was one of these evolving trends. The annual itself, with its accompanying trips and workshops, facilitated the gathering of women artists and the creation of collaborative works. Because women gather women, the strong presence of women artists involved with Persbook is due primarily to the circle of friends around the project, as Darzi states. A participatory section became an integral part of the event, with each one involving women artists from a selected region. Through these engagements, the intersection of feminist concerns and environmental issues grew more pronounced.

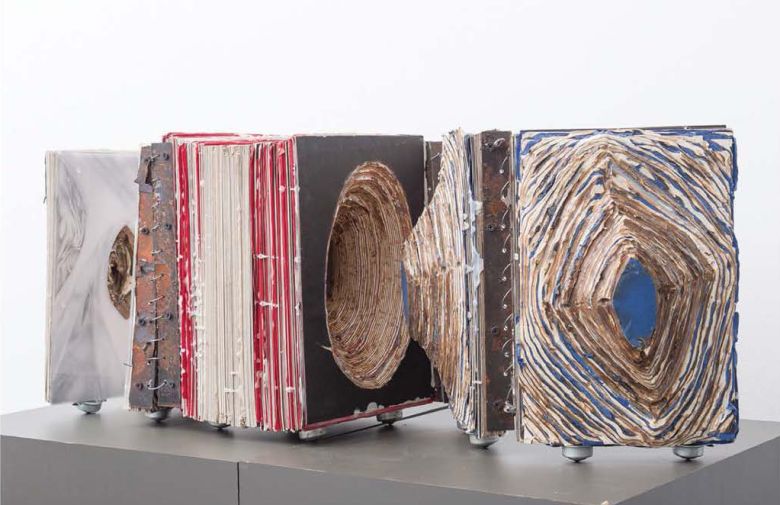

“Zero waste” was selected as the theme of Persbook’s 11th edition in an attempt to inform both the art community and audiences about the extent of environmental pollution and encourage them to “reduce, reuse, and recycle.” Darzi explains: “Tehran was chosen as the venue because it is the most polluted city in Iran in terms of consumer waste. One of the most concerning examples of contamination is plastic, which takes centuries to decompose. According to statistics, only 9% of non-degradable waste is recycled each year, meaning that 91% ends up in landfill. The “zero-waste” movement challenges people to rethink their approach to waste and encourages them to cut the amount of non-biodegradable waste that is produced, buried, incinerated, or discharged into water bodies by participating in responsible production and consumption practices.”5

Although Persbook has sought to create a relatively open space for the exhibition of contemporary art, it has nevertheless remained cautiously respectful of the state’s political and cultural boundaries. Taboo subjects are carefully avoided so as not to provoke sensitivities. In Karimi’s word: “Darzi’s Persbook events deliberately avoid overt social or political messages. In catalogs and brochures, in interviews and news statements, she has framed these efforts in terms of a benevolent discourse surrounding the celebration of community, the environment, and the decaying heritage in the desert.”6 However, this attitude has resulted in a generally flattened atmosphere. As Mahsa Nejat observes: “While a feminist approach is expected to be critical, such an aspect is not quite visible in the Persbook. … It tries to survive in the Iranian art scene by avoiding conflict with political and regulatory institutions. Therefore, in order to proceed through this passage and include feministic works, it has to promote a metaphorical and symbolic language to escape facing social and legal audits. Obviously, the use of a metaphorical language deviates from the explicit expression of concepts and slows down its critical attitude.”7

Persbook’s survival is due to a flexible, patient attitude, which has guaranteed its growth. As Karimi observes, “There is a wealth of creativity and expression that still waits to be explored within the broader context of Persbook, a platform that has evolved and grown over a decade, offering new insights and perspectives year after year. As I reflect on the past and present, I anticipate the boundless potential for artistic and societal transformation that Persbook will continue to unlock during these critical times and hopefully in the years ahead.”8 While there have been numerous competitions, collaborative projects, and initiatives in Iran over the past few decades, not all of them have stood the test of time. Persbook deserves recognition for its resilience, perseverance, and commitment. This year, it will launch its twelfth Annual of Contemporary Art event.

1 In an interview with Helia Darabi, Tehran, October 6, 2023.

2 Pamela Karimi, Alternative Iran: Contemporary Art and Critical Spatial Practice: Stanford University Press, Stanford (2022): 118-119.

3 In an interview with Helia Darabi, Tehran, October 6, 2023.

4 Mahsa Farhadi Kia, “On the 6th Persbook Contemporary Art Annual,”, Tandis, No. 324, May 2016.

5 In an interview with Helia Darabi, Tehran, October 6, 2023.

6 Karimi (2022):120.

7 Mahsa Nejat and Sadreddin Taheri, “Ecofeminism in the Contemporary Art of Iran (Case Study: Persbook Event),” Jamee Shenashi Honar va Aabiat (Sociological Journal of Art and Literature) 14, no. 2 (University of Tehran, 2023): 161–81.

8 Pamela Karimi, “Artistic Bodies and Daily Acts of Freedom,” Persbook, 2023, persbookart.com.

Helia Darabi, “Persbook: A Decade of Creative Resilience,” in mohit.art NOTES #7 (November 2023); published on www.mohit.art, October 27, 2023.