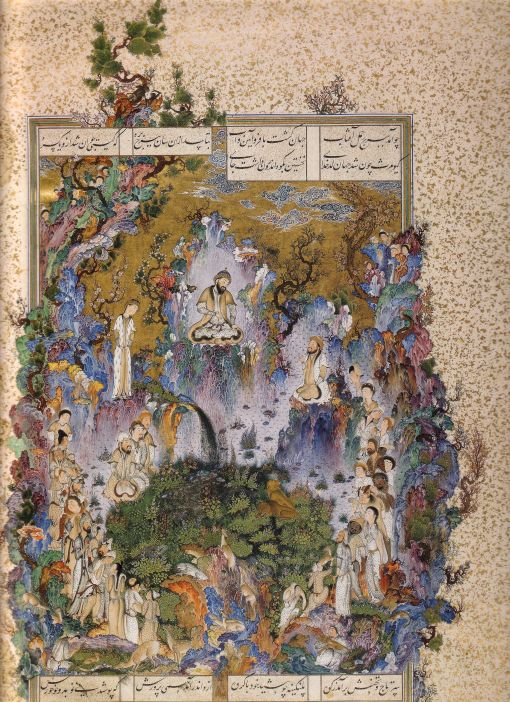

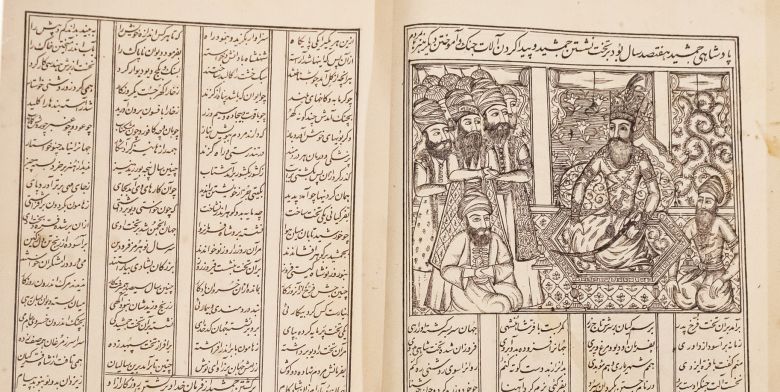

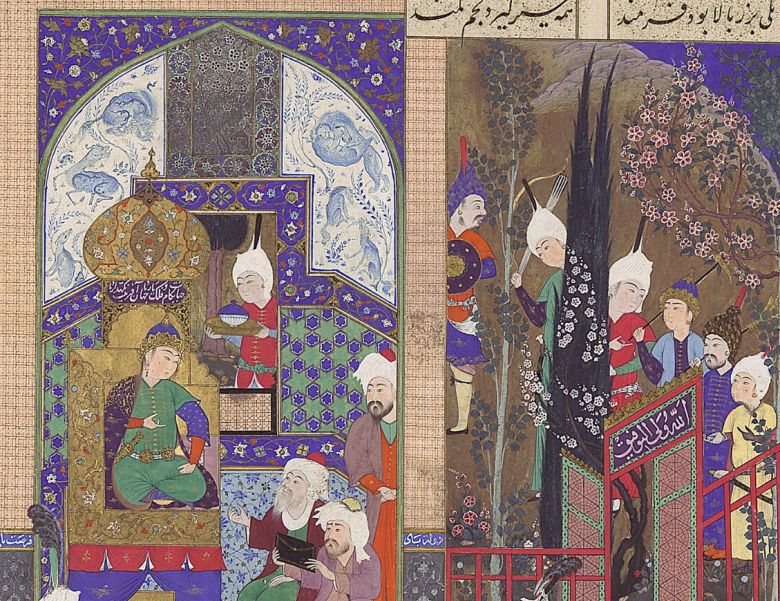

Shahnameh (شاهنامه, Book of Kings), is Iran’s most significant national epic. Abuʾl-Qāsem Ferdowsi, the poet who composed the book, was born in 940 CE into a family of small landowners in a village near Tus, in the Khorasan of Iran. According to the biographies, he completed Shahnameh around 1010 CE. Considered a part of what is called “world literature,” it has been widely translated and admired by readers all around the world. While it is known as a long epic poem, it can be distinguished in many significant ways from other epic books,1 and its functions cannot be confined simply to a literary genre. It consists of rich cultural aspects, including historical evidence, political thought, moral principles, mythical and religious interpretations, morphological roots, and so many other contributions that have been extended in the Persian-speaking world, from India to Mediterranean shores.

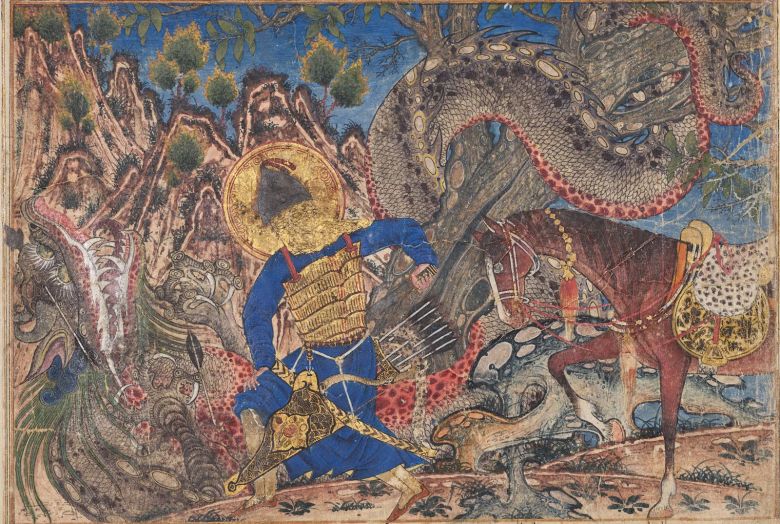

As the title implies, Shahnameh narrates a royal chronicle. What Ferdowsi presents to us is a chronological account of Iran’s ancient past from the time of the first primordial king to the Arab invasion. What is important, however, is that Shahnameh simultaneously presents historical and fictional stories, which, in a wider perspective, contain descriptions of the rise and fall of dynasties, the king’s rule, and heroes who battled with natural and supernatural creatures, all organized into a long versification. The first question that arises, therefore, is whether Shahnameh should be categorized as literature or whether we should consider it a historical book due to its political-historical recognition over the past centuries. Modern Shahnameh studies have often debated this question, giving rise to various attitudes toward the text. The dominant response belongs to the scholars who decided to divide the text into two opposite parts: history and myth. In this sense, Shahnameh is a combination of real and fictional stories of the past composed in a literary form. Being seen as a great window into Iran’s past, however, has meant that Shahnameh has been the single text that, throughout the centuries, has functioned both as a primary resource for historical genealogies and historians’ writings and as an inspirational text for poets and writers. So, how might we read and interpret a single text in the face of this severe opposition? Should we divide it, too? If so, what would then happen to the text’s unity? This essay intends to briefly set out these questions, claiming that what has united and reconciled these two conflicting realms is the very thing improperly conceived as pointless, ornamental, and superficial: Shahnameh’s poetic composition — those imaginative verbal schemas that work together to create a unique, coherent, meaningful image of the past.

It is impossible to reconcile history as “what really happened” and fiction as “fantastical stories.” Such a dichotomy leads us to separate research fields. But Paul Ricoeur, one of the great hermeneuticists of the twentieth century, tried to resolve this dichotomy in his narrative theory. By emphasizing how productive imagination has contributed to human knowledge, he claims that historical narrative isn’t a copy of real events, neither is fiction completely disconnected from the real world. Rather, both refer to reality in their specific way, based on their particular intentionality. What is at stake, however, is that their reference to reality is not direct, since these discourses, in fact, belong to the same ground: the poetic sphere. Historical and fictional narratives, Ricoeur maintains, are poetic compositions dynamically constructed through imaginative schemas such as narrative and metaphor. Grasping heterogeneous components and concepts together, this poetic operation articulates a meaningful image. To use Ricoeur’s more technical terminology, this configurating operation constitutes an “emplotment” as an active organization of events, rather than a static structure.2

Emplotment is a new being, a new meaning, that emerges through language — a new image in the world. As Ricoeur insists, the text’s poetic act extracts a figure from the discordant elements and provides a unified narrative from a chronology of episodes to produce a meaningful configuration that leads to a thought.3 This new image, however, does not refer directly to the real world but rather consists of a complex, indirect, poetic reference passing through a linguistic operation, including narrative, metaphoric, and symbolic structures upon which the whole text is constructed. He concludes, accordingly, that this poetic composition produces a surplus of meaning that augments the real world. Indeed, the poetic reference suspends reality to remake it. That is to say, poetry redescribes the world, refigures it, and, through this refiguration, extends reality.4 This extended reality constitutes a new world, a possible world, that goes beyond the irreconcilable dichotomy of history/fiction, and it — without reducing either to the other — unfolds a horizon that allows us to think about the past through this poetic language.5 This new world contributes to our self-understanding and changes our vision of human life and the world. To grasp the text’s meaning, therefore, this hermeneutic interpretation invites us to consider the whole poetic construction as it unfolds the world of the text. Thus, this approach opens up a way for us to go beyond the dichotomy of fact/fiction or history/literature and see Shahnameh in its grand narrative as a poetic composition, as a new world.

The arguments over Shahnameh, being more concerned with whether it relies mostly on an oral tradition or some specific written source(s), have paid little attention to the text’s configuration and its creative way of narrating. They overlook the complex composition, which brings about complex meaning. What is at stake here is the new world that the text’s specific linguistic reconstruction unfolds, indicating how Shahnameh deviates from its sources and other similar contemporary texts in narrating the ancient past.

Given the significant role of emplotment in creating meaning, we must refer to the grand narrative of the text as a whole. Among the different designations assigned to this grand narrative by the text itself, “sokhan” (سخن, speech/narrative) — describing the format of the text — is the most frequent; it is also most relevant to the concept of emplotment. Shahnameh is generally referred to as “Kings’ and Noblemen’s Sokhans,” relaying stories of characters who stand as the protagonists of specific eras. While a severe distinction seems to separate the two parts of the book, mythical and historical, all the stories are enveloped within a composition that creates a common ground, such that the historical stories become fictional as much as the fictional ones represent a historical vision. This unity arises from the emplotment, which rests upon different verbal schemas, and these schemas, above all, deploy symbols, metaphors, and narrative techniques that extend throughout every single story. To understand how this unity works, it is necessary to analyze the narrative structure, that of sokhan.

The term “sokhan” when applied to Shahnameh, however, signifies not only narrative but also action, written and oral speech, decision, language, incident, thought, and event, which have been mentioned in the recent Shahnameh’s dictionaries as well. All these notions taken together constitute a twofold meaning: the action itself (practical or theoretical), and the story of the action. Therefore, it can be claimed that sokhan in Shahnameh simultaneously signifies the poetic expression of an act and the act itself. In other words, the narrative here is an act; it works. This work appears at two levels: first, in the apparent contents of the stories, which implicitly or explicitly point out the work of sokhan; and, second, in the more fundamental function of Shahnameh as sokhan.

Operating on the first level, some of the text’s stories emphasize the work of sokhan. For instance, “The Story of a Village Which Was Ruined and Revived by One Sokhan”6 narrates the story of Bahram Gur, one of the great Sassanian kings. In this story, a stupid suggestion by a mobad (Zoroastrian cleric) leads to the destruction of a little village, to the extent that the area becomes as chaotic and horrifying as the Day of Judgment, and the inhabitants flee. The whole village becomes rundown: trees wither, irrigation ditches dry up, houses fall into ruins, fields lie fallow, and men and their flocks are nowhere to be seen. After a year passes, however, the mobad’s wise advice to the people revives the village again. The poet concludes that:

One sokhan was enough to bring this ancient village to its knees,

And one idea was enough to make it prosperous again7

بدو گفت موبد که از یک سخن]

به پای آمد این شارستان کهن

همان از یک اندیشه آباد گشت

[دل شاه ایران از آن شاد گشت

The second and more important level refers to Shahnameh itself as sokhan — a new world constituted through a vast poetic sphere. Indeed, sokhan works through its complex narrative techniques, which are highly subtle and consist of many aesthetic procedures. The book’s narration, at first sight, comprises stories unequal in length, including metaphorical prologues and epilogues that often convey meanings of human life and death, moral advice, descriptions of nature and characters, and so on. To give one example, one of the most frequent devices deployed in these parts is the anthropomorphization of “zamān” (زمان, time). Opening and closing a window to the story through implicit poetic explanations, these descriptions shed light on the stories contained in Shahnameh. In fact, this narrative configuration continually thrusts the reader ahead through expectation and then pulls them back to the beginning to tell them something about the story. However, metaphors are not confined to the prologues and epilogues but rather extend through the story itself. Time, for instance, plays a decisive role in the figures of harvester, actor, and magician in the stories themselves to provide a specific worldview. Constituting a great sphere of meanings, this configuration provides retrospective and prospective views that cause the reader to see the story through a poetic realm, not only uniting the elements of one story but also gathering all the stories into one coherent plot — sokhan. Going beyond figures of speech, the interwoven metaphorical network connects various concepts and worldviews. Stories, therefore, are related to each other and to the whole narrative in a complicated, poetic way. This imaginative structure is the very character of sokhan, which resists division into irreconcilable parts. It works as an integrating operation, grasping all the various layers together.

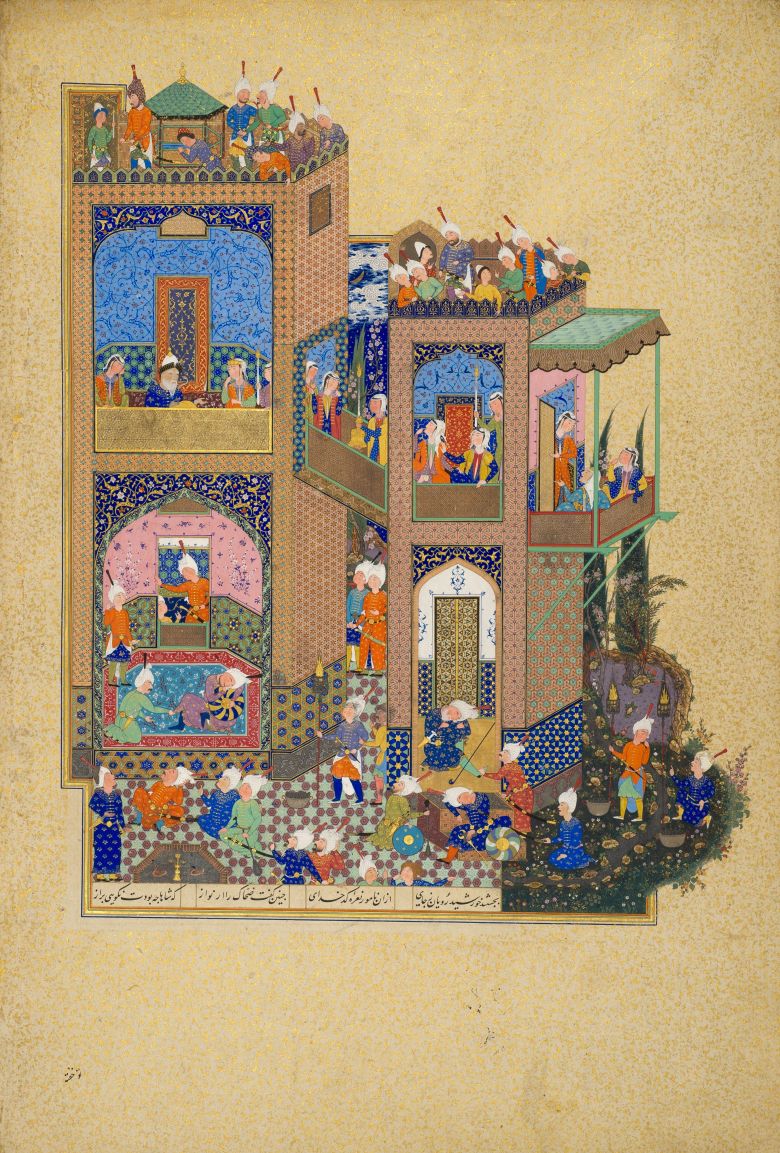

One of the most significant metaphors used to characterize the integrating function of sokhan is the “kākh” (کاخ, palace). In Ferdowsi’s metaphor, sokhan is seen as a great palace impervious to destruction by the passage of time:

I have built a grand palace of poetry

That storm and rain shall never mar.

Ages will pass over the book that I have writ

And those of wisdom will always read it8

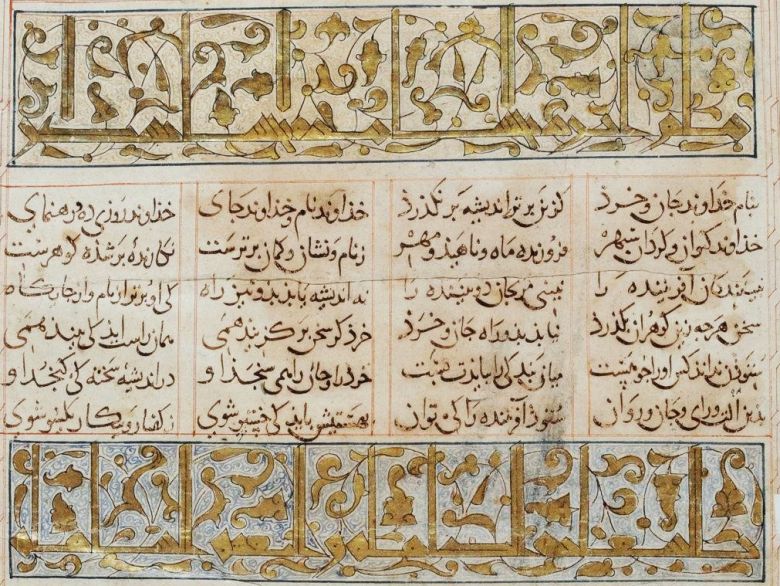

پی افگندم از نظم کاخی بلند]

که از باد و باران نیابد گزند

بر این نامه بر عمرها بگذرد

[همی خواندش هر که دارد خرد

This palace represents sokhan as a magnificent monument that conveys the grand narrative of Shahnameh as an integrated, lasting text — a spacious building constructed by each of its elements, brick by brick. All the various components participate in building a great palace: windows, labyrinths, cellars, rooms, alcoves, baileys, towers, and so on. In this respect, it is of the greatest importance to see it as a unified construction. Moreover, this metaphor entails an implicit meaning. Sokhan, here, takes the form of a palace directed toward the future. This palace/writing consists of past stories and incidents constructed in the poet’s present to survive into the future. Ferdowsi’s sokhan accordingly is not simply a book about past and bygone stories but also includes important implications regarding time, history, and the poetry itself. The present tense here serves as a basis for inviting the unknown reader to read the past stories. But three tenses are simultaneously at play in this image. By giving a temporal meaning to this metaphor — and by extension to the whole narrative — the entanglement of remembered past with the poet’s present and future (the reader’s present) confers a historical depth to the stories and takes them beyond simple successive incidents in a chronology. The retrospective and prospective attitudes in the narrative’s internal structure are again repeated, but in a wider scope, in relation to the grand narrative as an interpretation of the past. This is the work of Shahnameh, how its emplotment operates and creates a world. This poetic power allows the poet to tell a story and to think about it. In this way, he is at the same time recognized as the “shāer” (شاعر, poet) and “hakīm” (حکیم, wise man).

In the final analysis, it can be said that sokhan, the grand narrative of Shahnameh, isn’t confined to a simple chronological versification of past stories, whether historical or mythical; rather, it frames a unity constructed upon the various events and stories preserved in scattered documents and minds and also incompatible notions and worldviews. What is at stake, consequently, is this artistic composition’s elimination of the division between reality and fiction and their reconciliation in poetry. Therefore, all the various functions of Shahnameh, from the epistemological to the ontological, should be sought through this poetic world as a foundation.

1 Shahnameh is distinguished by its multiplicity of themes, characters, and generations, as well as its narrative techniques appealing to an ancient imaginative tradition.

2 Paul Ricoeur, Time and Narrative, vol. 1, trans. Kathleen McLaughlin and David Pellauer (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984), 50–53.

3 Ricoeur, Time and Narrative, vol. 1, 65–66.

4 Ricoeur, Time and Narrative, vol. 1, 80.

5 Paul Ricoeur, “The Function of Fiction in Shaping Reality,” Man and World 12 (1979): 135–39.

6 In Dick Davis’s English translation of Shahnameh, the title of this story is translated as “Bahram Gur’s Priest Ruins and Revives a Village,” which omits the term “sokhan” as the tale’s keyword. See Abuʾl-Qāsem Ferdowsi, Shahnameh: The Persian Book of Kings, trans. Dick Davis (London: Penguin Classics, 2016), 807.

7 Abuʾl-Qāsem Ferdowsi, Shahnameh, 4 vols., ed. Djalal Khaleghi-Motlagh (Tehran: Sokhan Publication, 2017), 4:499.

8 Ferdowsi, Shahnameh, 2:793.

Neda Ghiasi, “Sokhan as a Poetic World in Shahnameh,” in mohit.art NOTES #13 (October/November 2024); published on www.mohit.art, September 27, 2024.