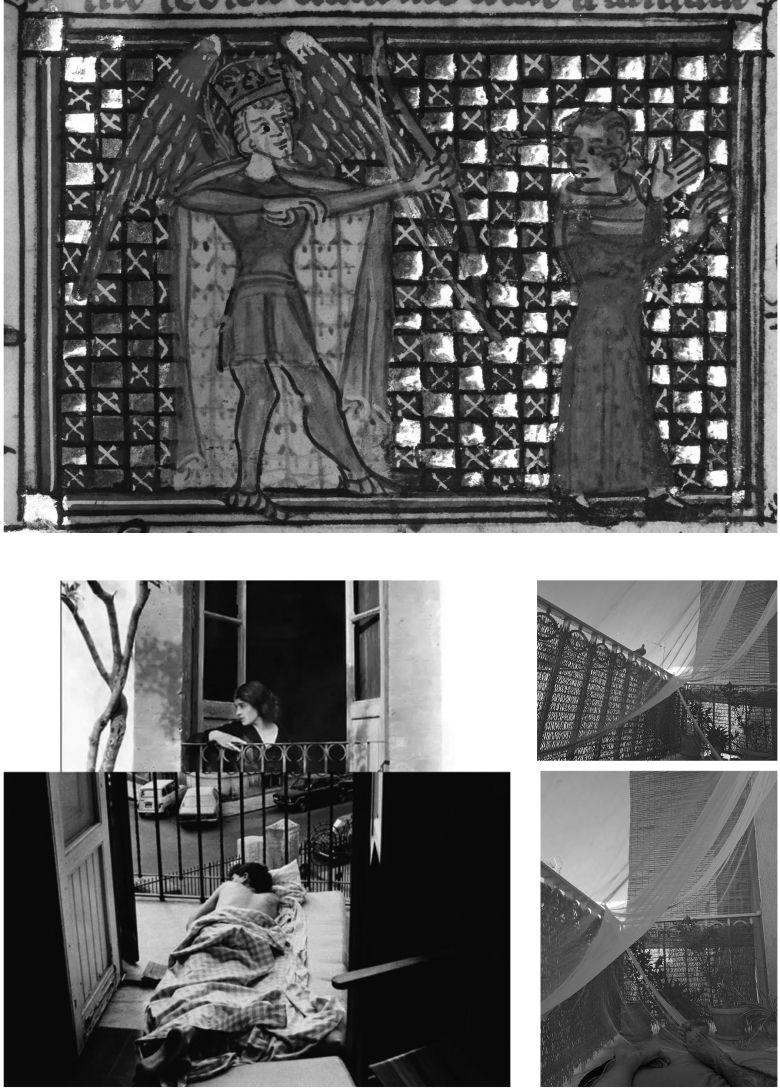

The love story of the poet Ahmad Shamlou and his beloved Aida1 begins on an ayvān.2 Aida describes it thus: “I went to the balcony to watch the flowers and the trees. … I turned around … and I saw a man standing on the ayvān of the house next door … watching me … our eyes met.”3 About eight hundred years earlier, during his adventures through the Eastern Roman Empire,4 Sheikh San’an5 also encountered a Christian (Tarsa)6 girl for the first time on an ayvān and fell in love with her.

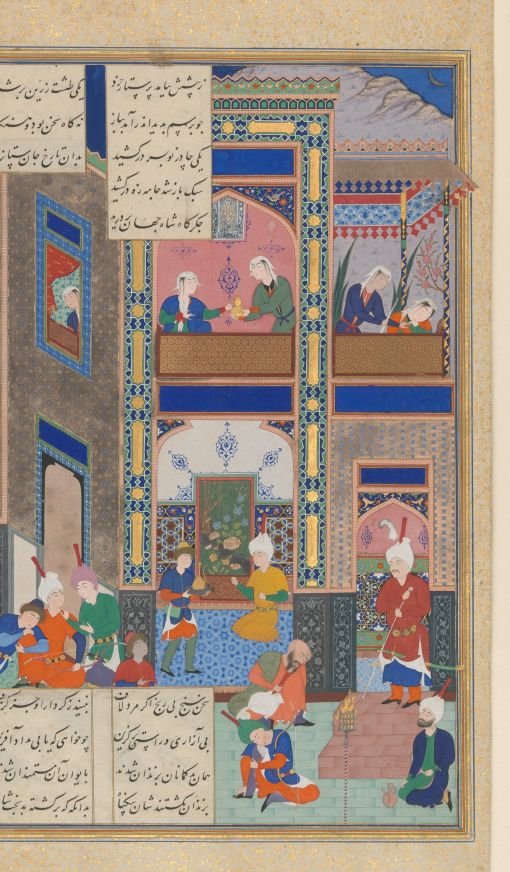

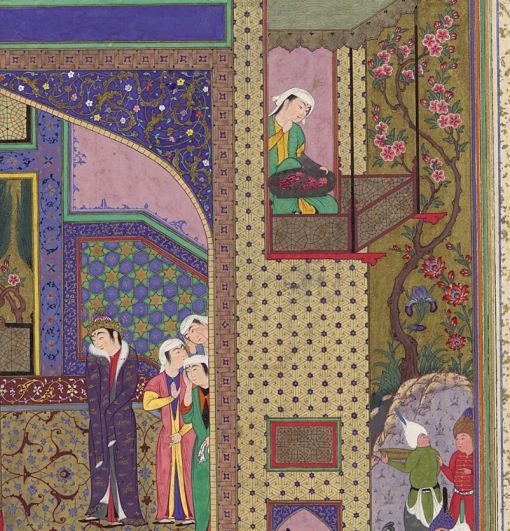

Isn’t it bewildering that, after hundreds of years, someone once again fell in love with a Christian girl7 who had stepped out on an ayvān? Attar8 , the poet who wrote Sheikh San’an’s story, finds it quite believable that a Christian girl would step onto an ayvān and that Sheikh San’an would fall in love with her, as such encounters were familiar experiences then. The ayvān was an interstice through which maidens could reveal themselves. Iranian painters have sometimes incorporated a maiden in their paintings of manzar.9 It is as though to their imaginations the ayvān is the locus for the appearance of beauties, reaching its ideal form when someone stands on it whose visage and presence would be delighting. Here we find the first role of the ayvān manifesting itself: the ayvān is the “house’s windblown hair” — a decorated space that reveals the beauty of the house10 and its owner.

As a teenager, I passed my phone number to the neighbor from the ayvān/balcony of our house. I cannot clearly remember what attracted me to this neighbor — the ayvān had tempted me to befriend someone who was, in fact, a total stranger. That other world and other life revealing themselves behind the windows bloomed on the ayvān. Traces of life constantly called forth new interpretations: Ah, now the next room’s light is on. Will someone step onto the ayvān? These experiences of the ayvān had the effect of motivating me to view the world through the lens of semioticians. Drawn curtains, like the melody of a gramophone playing “La Malagueña” coming from Aida’s house,11 were like a sign for me and built a maze leading to the love of a faraway other—a love for a faraway other, even if it is the love of a Sheikh for a Christian girl.

Why is the ayvān dressed with the dream of love? Does the ayvān offer anything special? Anything other than a beauty sitting in a faraway manzar? Is there anything but ambiguities and signs that must be interpreted and decoded? It is here that we should ask ourselves what the ayvān wants. The ayvān breaches the house’s wall and faces the world outside. One can say the same about the window. The ayvān, however, is different in that it creates a place to stay and face the outside. Hence, the ayvān shows us that there is a desire in the house itself. The house desires to turn its gaze to the outside. And this is what makes the dream of love suitable for the ayvān. Just as desire opens up one person to another, the ayvān opens up the house to the exterior. Like a smiling face and an open heart, the ayvān welcomes an unknown relation and event.

If you sit on an ayvān in Tehran, you will see pigeons and laughing doves flying from one ayvān to the next, as if carrying messages from one ayvān to another. They are, in fact, following their own desire. With its extended and open space, the ayvān offers these flights and searches for love a place to land. With invisible threads, the ayvān connects the love stories of birds to each other. I am not a Marcel Proust, able to describe the vertigo of this amorous and passionate search. Just try to imagine that these threads make a web no less magical than that of a spider, and this web captures the unreachable sky. The wind itself is rendered visible thanks to these birds and their threads. A bird dragged and thrown in a strong wind, or a mild breeze giving the flight of a swift that gentle extension and bend. For a few weeks, these migrant swifts, on their way from Africa to Northern Asia, fly in the skies of Tehran. They remind us with their loud cries that the wind itself comes from a faraway place. The ayvān renders the immeasurable sky visible and hangs us to the heights of the star Capella, and by finding the invisible wind, it takes us to the beaches of Zanzibar. With these invisible threads of dreams, the ayvān opens its arms toward the horizon and to the heights of the sky, arms extending as far as the eye can see and the wind can fly.

In Iranian paintings, one can observe that when a tree grows on the side of an ayvān, it twists like ivy around the ayvān so that the house and the tree become intertwined to the point of being indistinguishable. At night, starlight shines on the ayvān, or, as Ḥafeẓ describes it, the stars kiss the ayvān.12 The ayvān allows the trees to embrace each other with love and the stars to kiss. It somehow looks like unroofed ruins that welcome the moonlight in. But unlike ruins, the ayvān — or mahtabi13 — does not have this quality due to the absence of a ceiling or walls. The ayvān is first and foremost a different way of relating to the exterior world. We see the same relation in the painting The Marriage of Siavash and Jarirā (1525–30) where the girl in yellow has wrapped her arms around the column of the ayvān. The ayvān narrates the allegory of a house that has wrapped its arms around the neck of the world around it.

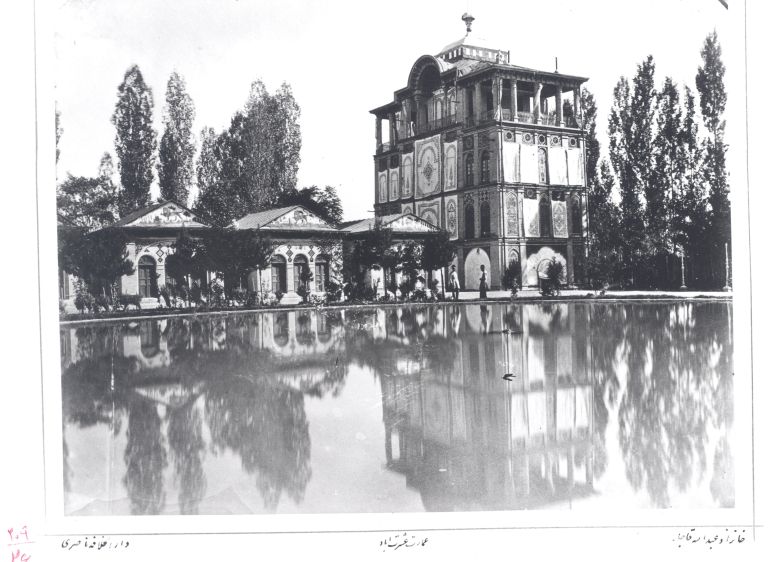

Iranian architecture features a hierarchy of open, half-open, and closed spaces. These three types of spaces have manifested themselves in various ways throughout history. The ayvān, a half-open space, has been one of the main components of Iranian architecture since at least the Parthian Empire (247 BCE to 224 CE).14 These half-open spaces either face the inner yard, as in the houses of Kashan, or the garden, like in Fin Garden, or they overlook alleyways, as seen in the houses of Abyaneh village. Whether the house has a garden or not, it still requires an ayvān — a space to connect to the outside world.

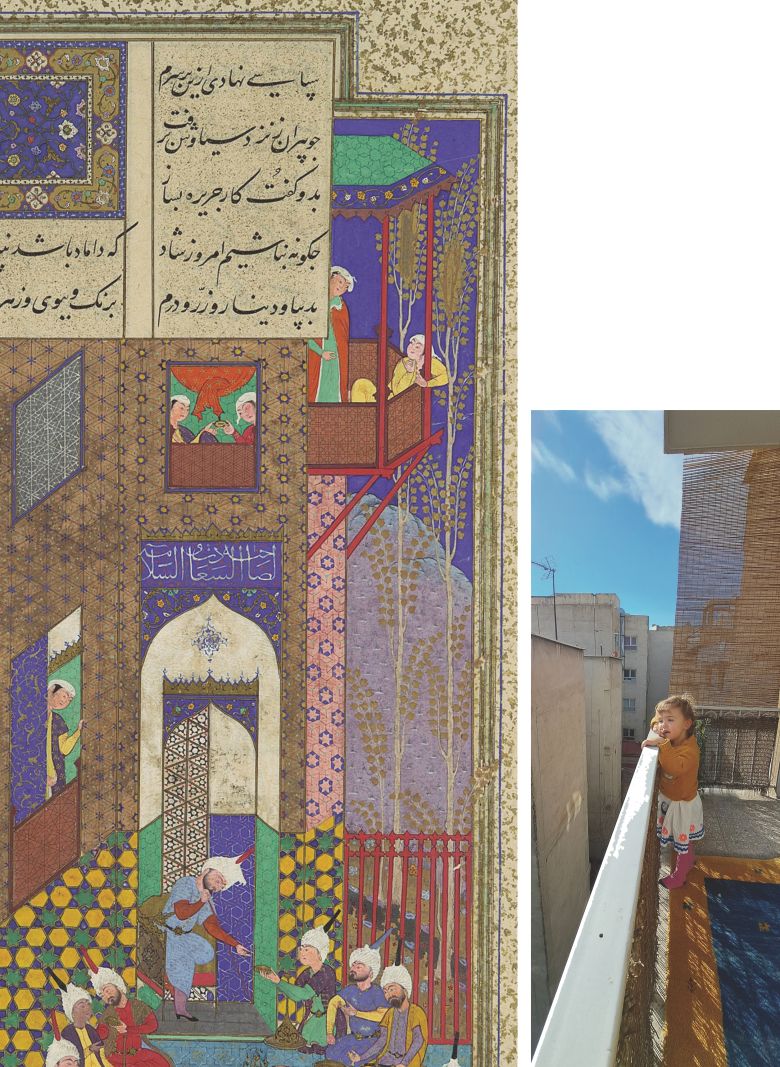

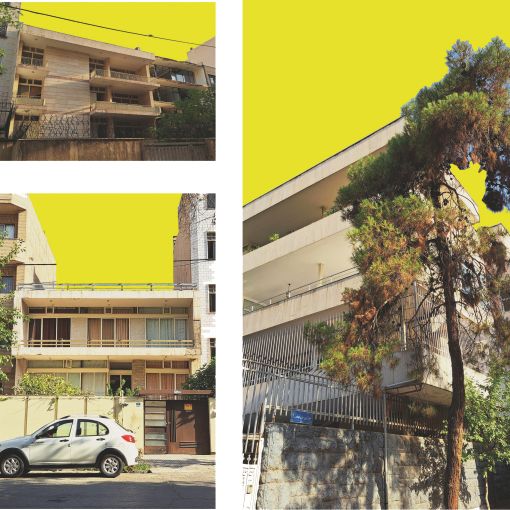

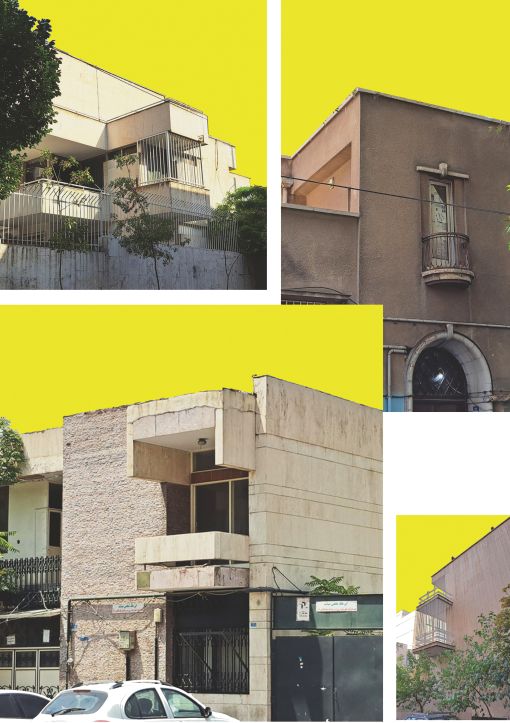

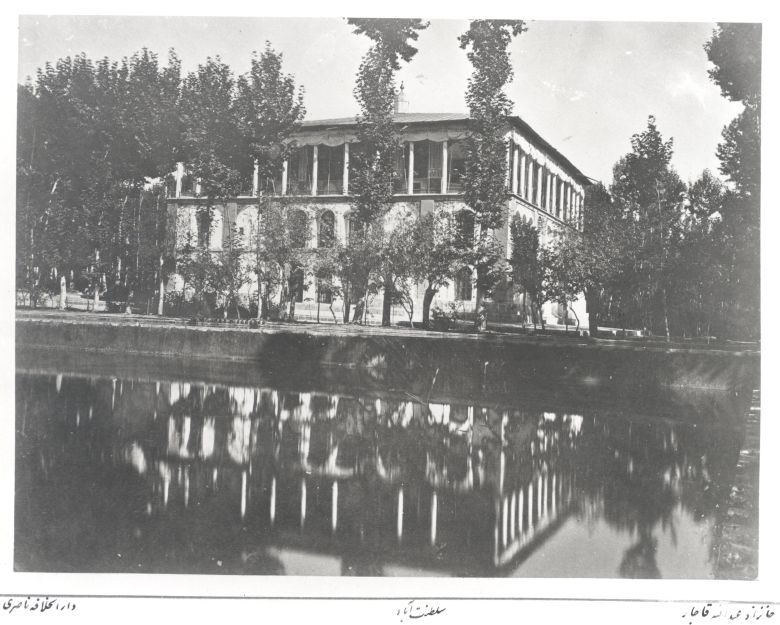

The ayvān continued to play a pivotal role into the modern era, especially considering that the modern apartments couldn’t each have an independent yard. Ahmad and Aida’s love story in the 1960s unfolded on one of these balconies. In modern Iranian buildings, ayvān either covered the whole building’s façade or was an integral part of it. Therefore, it had considerable visibility to the passers-by and became the subject of playful creativity for architects. Modern Tehran, whether in its residential apartments or its tower complexes such as Eskan and Atisaz, was a vast exhibition for these manifestations of ayvān.

After the 1979 revolution, the thousand-year history of the ayvān almost faded into oblivion. People retreated into their homes, withdrawing from spaces where others could see them. The regime prevented people from exposing themselves, and in the post-revolutionary constrained atmosphere, the people themselves were reluctant to be exposed. The ayvān no longer seemed like a safe space. Parties and gatherings were exiled to the inner spaces of houses and other private areas. The city ceased to be an attractive place. With the ban on public festivities,15 noise and air pollution became the city’s primary characteristics. Consequently, houses no longer turned their faces toward the city, and the ayvān followed suit. In many instances, such balconies were closed, effectively turned into rooms, cut off from the city, and hidden from view.16

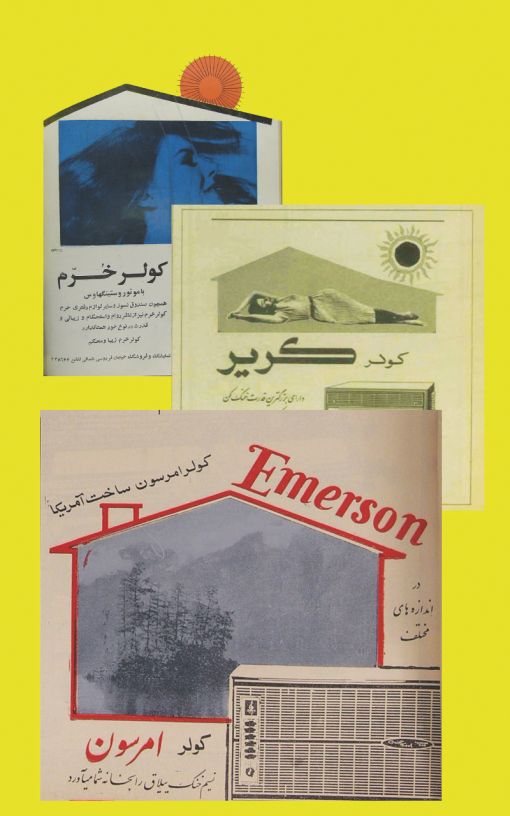

However, there was another factor involved. It was the rise of air-conditioning. Advertisements for air conditioners and ventilators, which became popular in the 1950s, encouraged people to remain inside their houses. This new custom replaced the tranquility people had enjoyed for years in half-open spaces, or in yeylaq.17

As the ayvān fell out of fashion, it came as no surprise that, in real estate, it no longer contributed toward a house’s or apartment’s overall value.18 With rising house prices, the ayvān became progressively smaller, to the point where it played no role for the house, let alone serving as a place of openness to the outside world or as a connecting point between the house and its surroundings. The outcome was houses without any ayvān/balcony, or yard at all, completely detached from their environment. One can even use the presence or absence of a balcony or an ayvān as a way to determine a building’s age.

In a folio of Shahnameh which illustrates the killing of Barmāyeh by the messengers of Zahāk (1520s), the house’s gate and the door of the ayvān are open, and the ayvān is empty. It is evident: this house is abandoned; its inhabitants have left. The wide-open doors and empty ayvān tell us that this house is deserted. These signs would have been familiar to the viewers of these paintings in their time. A manzar without a viewer shows us that Fereydoon is not here. Fereydoon’s ayvān is empty.

Isn’t it time to remove the veil from the ayvān? Will the city finally reveal its amorous face? Love for the faraway other that forms the basis of the city’s imagination was once born on the ayvān of the houses. The ayvān, especially in modern times, was a space that connected the city and the house. It was a space that opened up houses to the city and urban life, saving them from turning into prisons and isolated places. The ayvān invites us into itself.

wake up, winter is leaving

open the doors of the garden

let this curtain once and for all

leave and let appear the ayvān.

برخیز که می رود زمستان]

بگشای درِ سرایبستان

وین پرده بگوی تا به یک بار

.19[زحمت ببرد ز پیش ایوان

Translated by Golnar Narimani

1 Ahmad Shamlou, Iranian poet (1925–2000), and his wife Aida Sarkisian (b. 1939), of Armenian origins.

2 “Ayvān” has various meanings, but one of the more conventional meanings, as used in this essay, is a half-open space with a roof and a certain height off the ground, like a covered balcony. See Encylopædia Iranica, s.v. “Ayvān,” last modified August 18, 2011, iranicaonline.org.

3 Saeed PourAzimi, Aida Sarkisian, Sharing the Light under a High Roof (Baam e boland e hamcheraghi), Tehran, 2020, 35.

4 Translator’s note: Rūm (Arabic: روم [ruːm], collective; singulative: رومي Rūmī [ˈruːmiː]; plural: أروام ʼArwām [ʔarˈwaːm]; Persian: روم Rum or رومیان Rumiyān, singular رومی Rumi; Turkish: Rûm or Rûmîler, singular Rûmî), also romanized as “roum,” is a derivative of Parthian (frwm) terms, ultimately derived from Greek Ῥωμαῖοι (Rhomaioi, literally “Romans”). Both terms are endonyms of the pre-Islamic inhabitants of Anatolia, the Middle East, and the Balkans and date to when those regions were parts of the Eastern Roman Empire.

5 The story of Sheikh San’an, who falls in love with a Christian maiden, is part of Attar’s poem The Conference of the Birds. According to the story, Sheikh San’an, a Muslim leader, falls in love with a Christian maiden on his trip to Rome.

6 Translator’s note: People of Armenian, Christian, and Jewish origin were called “Tarsa” in Old Farsi.

7 Aida and the maiden from Attar’s story are both Christians.

8 Abū Ḥāmid bin Abū Bakr Ibrāhīm (ca. 1145–ca. 1221; Persian: ابوحمید بن ابوبکر ابراهیم), better known by his pen names Farīd ud-Dīn (فریدالدین) and ʿAṭṭār of Nishapur (عطار نیشاپوری; “Attar” means “apothecary”), was an Iranian poet, Sufi theoretician, and hagiographer from Nishapur who had an immense and lasting influence on Persian poetry and Sufism. wikipedia.org

9 Manzar: an ayvān from where one can observe things, almost like a balcony.

10 Numerous classical Iranian poems and paintings describe or demonstrate the decorations and ornamentations of the ayvān.

11 Sarkisian, Sharing the Light, 35.

12 Inspired by Ḥafeẓ’s poem تا ببوسم همچو اختر خاکِ ایوانِ شما.

13 A terrace (in Farsi bahārkhvāb, literally “spring bedroom”) or mahtābi is an open ayvān used as a sleeping space. “Mahtābi” is etymologically an adjective, derivative from the word for “moon.” The space is probably called mahtābi — or moonlit — as it is literally lit by the moon at night.

14 O. Grabar, “Ayvān,” in Encyclopedia Iranica.

15 By the “ban on public festivities” in the city, I refer to the closure of all bars and dance clubs and the ban on playing festive music and even on the presence of women in stadiums.

16 This hiding from view occurred in parallel with the hijab law, which made wearing the Islamic hijab mandatory for women

17 No precise English translation exists for this term; however, it literally means “countryside” or “summertime highland pasture.”

18 When it comes to an ayvān, which is open on some of its sides, only a percentage of the area counts in estimating the home’s price. A specialist determines this percentage and its net worth is calculated separately from the rest of the building.

19 Poem by Saadi Shirazi (1210-1292) CE.

Negar Saboori, “The Ayvān as the Scene of Encountering the Other,” in mohit.art NOTES #13 (October/November 2024); published on www.mohit.art, September 27, 2024.