—Where are you?

—Near Enghelab Square.

—Fine, we will wait for you to have dinner together.

—We just had dinner. Have you eaten?

—No, it’s too early for dinner.

—What time is it there?

—It’s only five-thirty.

—Ah yes, it is still day there …

When the “where” question is transformed into the “when” question, one experiences the temporality of spatial displacement. What used to be only space unfolds as a question about the temporality of spaces. The before of leaving, before of migration, is the timelessness of shared spaces. The after of immigration is living the temporality of that time immemorial, when memory scrapes the “im” from immemorial, so, memory as temporal displacement and living this displacement. Is there anything between that before and this after?

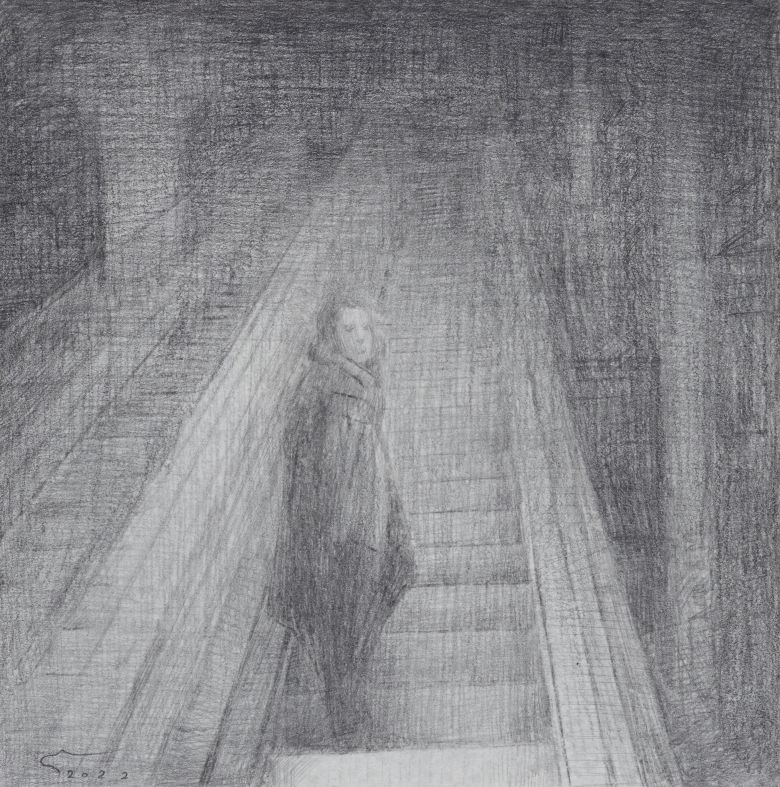

The art of immigration or immigration as present in art — and we do not use the word “representation” here, as it is not a question of rendering visible, in terms of the conventional meaning of representation, that which is inherently invisible — is often either about the after or the before of immigration, but mostly about the after, about the road, the sea, the boat itself, after one has left, has said goodbye, has perhaps shed tears. But the truly after is in the new country, land, society, the “I” living this after and remembering the before in its light. Is there any other time? This other time might be a passing moment, invisible, ephemeral, and yet as long as a lifetime — the minutes between the after and the before, a transitional moment, a moment of trans, across, beyond and ire: a going beyond, a waiting-to-go-beyond. Transition and transient have the same etymological root.

Moslem Khezri (b. 1984) is an Iranian painter, art critic, art teacher, and writer who has engaged with these in-betweens for many years. In the series We keep reviewing, he paints schoolchildren in classrooms, a difficult and paradoxical space for most Iranians, especially those born after the 1979 Iranian Revolution, who had to attend school under the pressures of an Islamic system. The specificity of these works lies in the fact that they are based on his own experiences as a school art teacher. Khezri has been a patient observer of ephemeral moments in the lives of young adolescents. Lives toward what? With what aims? Following which paths? Where do these young people go after school?

Which brings us to the current series In-Between. For many Iranians today, immigration is not a choice but a necessity, providing an evident purpose for a young generation who, in many ways, thinks more about leaving than staying. They choose to study subjects popular in countries where it is easier for them to go; learn English, German, or French toward the end of their studies; search endlessly for a degree, a scholarship, or a job; and save money for immigration costs. These are the adults of today, the adolescents of yesterday, for whom leaving is not a desire for new or different experiences but a need, a necessity, when future horizons are blurred and obstructed in a highly malfunctioning social system and a repressive political structure, in every possible sense of the word. Those who can leave, leave. Those who stay make an equally difficult choice, a transcendence of sorts, where real life and concrete conditions offer no other option.

And yet, this scenario is different from many other forms of displacement, as it is official; it is not as brutal as other types of immigration. These immigrants, for the most part, do not take a horrific boat trip across the ocean or walk in groups over mountains and borders. They leave by plane, from the airport: everything appears well-arranged, ordered. And yet, this is precisely where all deep, paradoxical feelings are located.

Khezri sets his series in the in-between space of the airport, at the very moment of farewell. The realist paintings are located in this borderland between the past and the future, the former a total disappointment, the latter a complete fog of uncertainty. Let us examine the topography of this space.

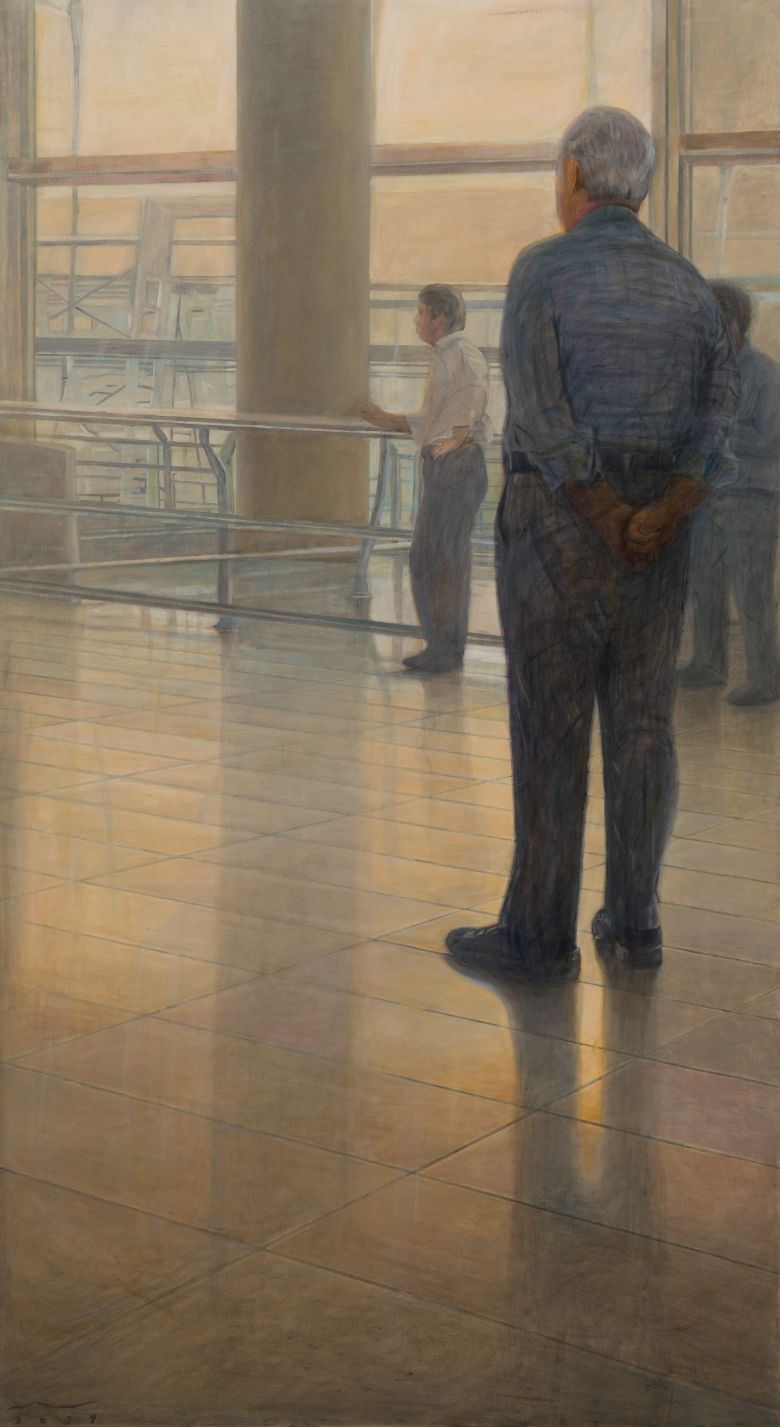

Imam Khomeini International Airport is sixty kilometers away from Tehran. Like many urban projects, it was hastily built after years of delay and many divergences from its architect’s original plan; it still appears unfinished today. The road leading to it is marked by the strong odor of urban waste. The airport itself looks like a hasty patchwork of architecture, made mostly to be just functional. Its interior, from the lights to the arrangement of seats and gates, could be described in one word: unfriendly. This airport is not viewed as a transitional space from which to depart for a holiday or a pleasant work trip — indeed, Iranians are rarely able to travel abroad for holidays. It is, first and foremost, a cold, unfriendly, and ugly space of transition. The space lets you know you are not wanted, that you can’t have any desires, but only a pure need, almost like a survival instinct.

In such a cold and unfriendly space dominated by the harsh presence of airport police, migrants go through a very intimate experience. How long does a farewell take? We recommend that you arrive at the airport at least three hours before departure. During these three hours, one’s private space becomes public and intimate life overflows into the public sphere.

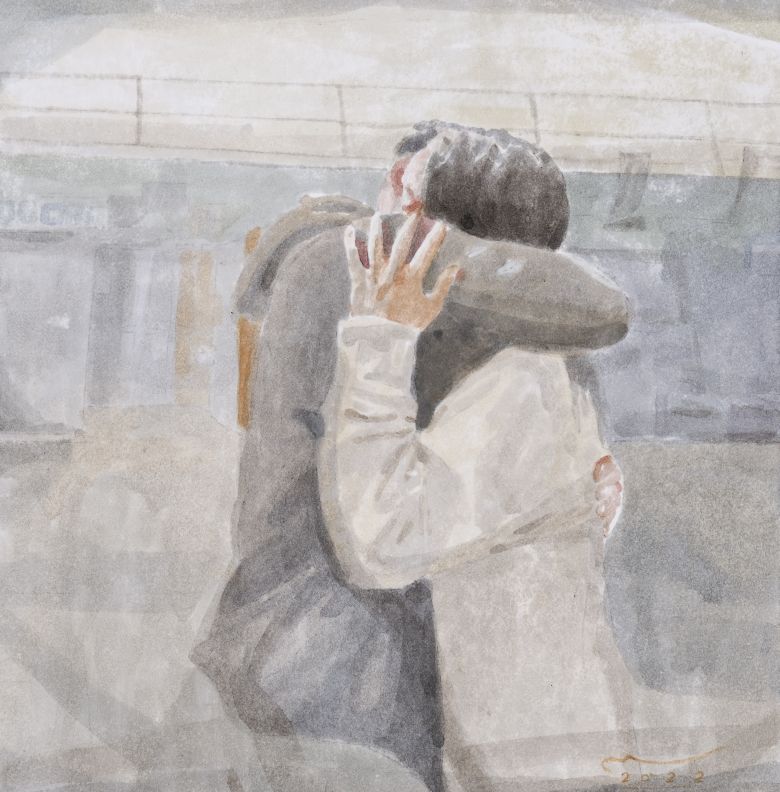

For decades, the Islamic Republic has heavily controlled and censored public space. No physical displays of intimacy, love, emotion, or sentiment are allowed in public, and this has created a private sphere entirely different from the public one, resulting in a double life or two parallel lives for many Iranians. The airport, however, ruptures this condition: the most private moments happen and have to happen in public. In this borderland space, the public and the private suddenly seem to overflow into each other and become intertwined. The intimate feelings that arise in the moment of farewell transform imposed divisions and lead to a reclamation of public space. In an instant, the cold departure gate turns into a stage for the sharing of emotions. People express feelings they have been banned from showing in public. They hold hands and embrace; they smell, kiss, and caress each other.

Khezri’s series sheds light on this moment. The works are realistic in style and rich in materiality and texture. Bodies, skin, clothes, and elements of the space, such as stairs, seats, and floors, all seem to be made of the same fabric. People and architecture are interwoven through the distribution of light and a continuity of color. In an interview, Khezri talks about how he spent days at the airport before beginning work on the project. He describes how people held each other tightly, as if attempting to capture the other person’s scent so it would remain with them after they had separated. What does this scent that remains look like? How does it alter the space?

In some of the works, the artist has removed various figures from the initial painting but intentionally left traces of them in the finished piece. Even though these ghostly figures have vacated the space, their traces remain, vestiges of the affective and emotional exchanges that have reclaimed public space from the controlled public space of state surveillance. These residual traces remind us of the nature of such in-between spaces, where time seems to stand still — like the people in Edward Hopper’s paintings who appear as if frozen between moments. This suspension of time opens up another dimension where the reclamation of public space becomes possible through the intimacy of the farewell, which traces and marks the space, transforming it. Now, what about the specificity of these figures?

The face and especially the eyes, the locus of looking and where light gathers, are traditionally viewed as mirroring our emotions, as the locus of expression and the source of our primary impression of the Other. But is the visage of the Other limited to their facial features? Let us indirectly borrow from philosopher Emmanuel Levinas and consider Gustave Courbet’s The Stone Breakers (1849), Gerhard Richter’s Betty (1988), and Andrew Wyeth’s Christina’s World (1948) as paradigmatic examples of an encounter where the other’s facial features are obscured. In Khezri’s paintings, we are rarely confronted with facial expressions; instead, he focuses on shoulders and heads caught in embraces and hand gestures in particular. Without showing the literal face of a figure, he presents their entire visage through how their body appears during a moment of rupture, of farewell, as they interact face-to-face with other figures and with the painter. In a conversation with philosopher Françoise Armengaud, Levinas stated that “without mouth, eyes or nose, the arm or the hand by Rodin is already a face.”1 In viewing the visage of the Other as their mode of appearance and not literally as their facial features, we might be able to see in Khezri’s choice to show not faces but gestures, not eyes but hands, not lips but shoulders — namely, his choice not to disclose the face — a movement away from conventional methods of producing empathy through facial expression toward an entirely different relation to the Other. In the holding of hands, in the entanglement of bodies overwhelmed by the moment, in an embrace, we see a rupture in state-permitted expressions of sympathy and maybe grasp in the flickering non-visibility of faces the non-representability of an ethical moment, which only comes forth in Levina’s formulation “ethics is an optics” — optics as observing and being observed,2 in this case, both the farewell happening in front of us and ourselves as the ones witnessing it and, like the painter, staying, not leaving.

It is rare to encounter an Iranian in the past few decades who has not inhabited one of these roles: either the one who leaves or the one who stays. The novelty of Khezri’s In-Between series lies in his observational position as the painter: the observer is the one who stays. Many Iranian artists dealing with immigration often take their own perspective as the one leaving or comment on the idea of immigration in a more general way. Khezri’s works, however, seem to have been painted from the perspective of a participant. The artist himself explains in an interview that in the past few years, he has witnessed the ever-increasing migration of his friends and loved ones, and it is this shared experience that motivates the current series.

1 Emmanuel Levinas, On Obliteration: An Interview with Françoise Armengaud Concerning the Work of Sacha Sosno, trans. Brian Alkire (Zurich: Diaphanes, 2019), p. 35.

2 Johannes Bennke, introduction to Obliteration. Für eine partikulare Medienphilosophie nach Emmanuel Levinas (Bielefeld: transcript Verlag, 2023).

Golnar Narimani, “Topography of Displacement: A Note on Moselm Khezri’s Painting Series In-Between,” in mohit.art NOTES #9 (January 2024); published on www.mohit.art, December 22, 2023.