The one who touches the land touches history

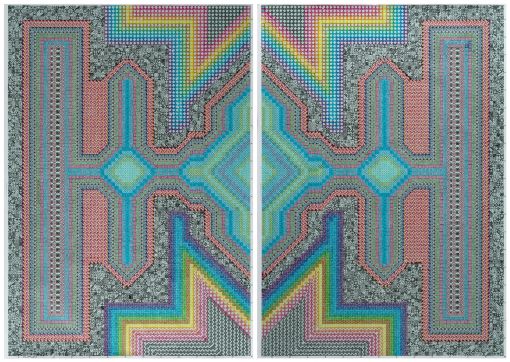

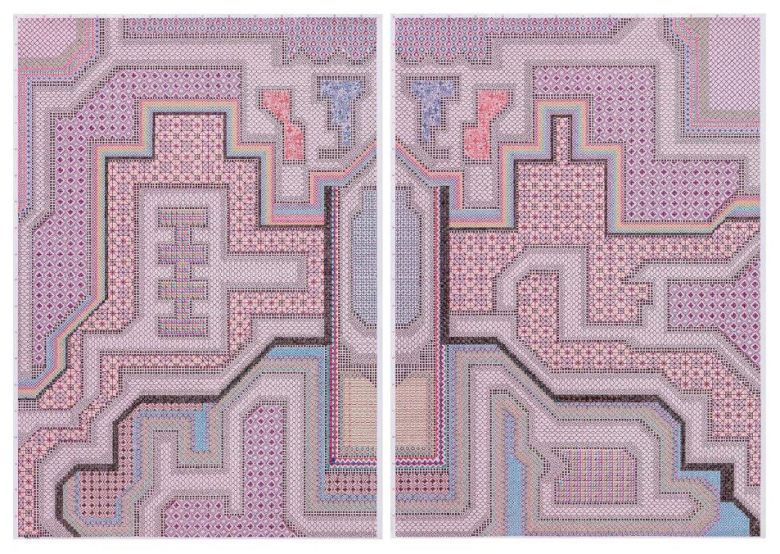

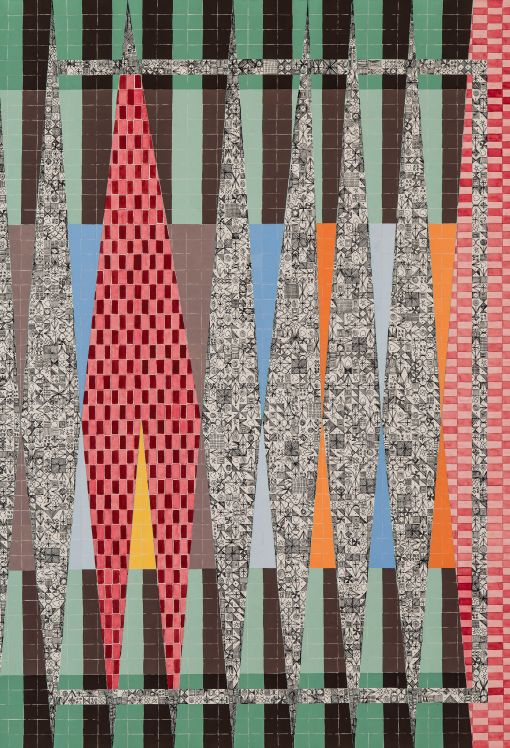

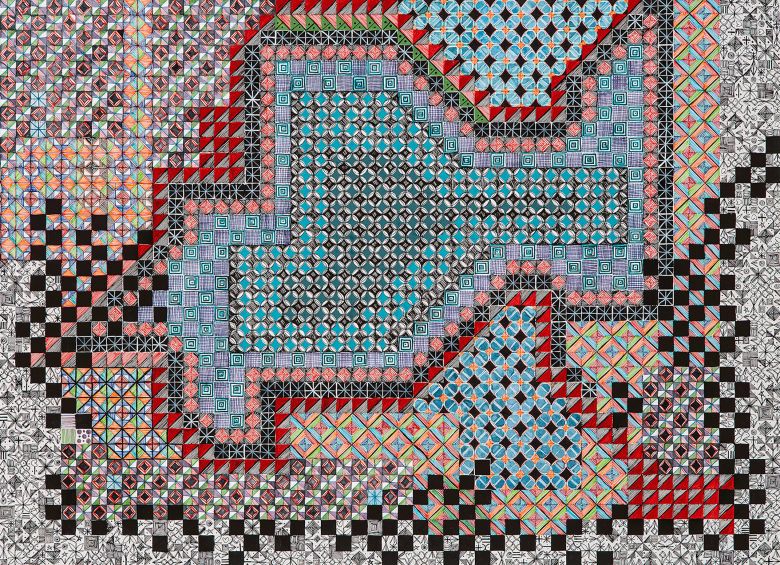

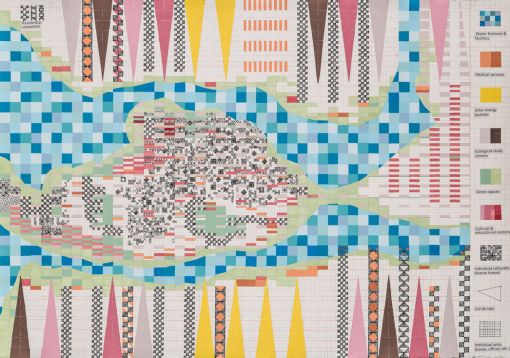

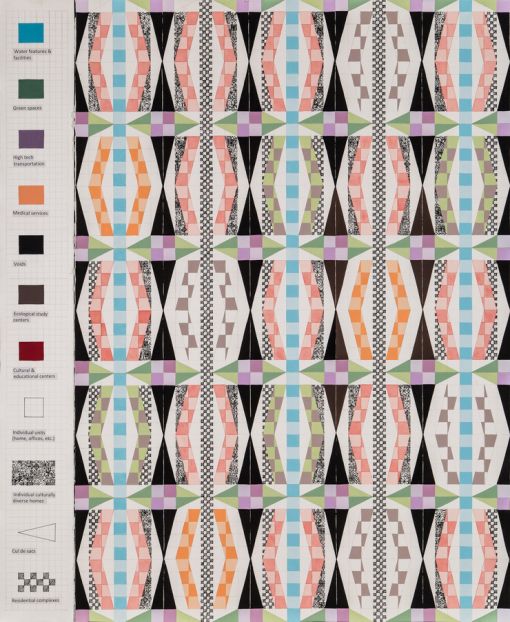

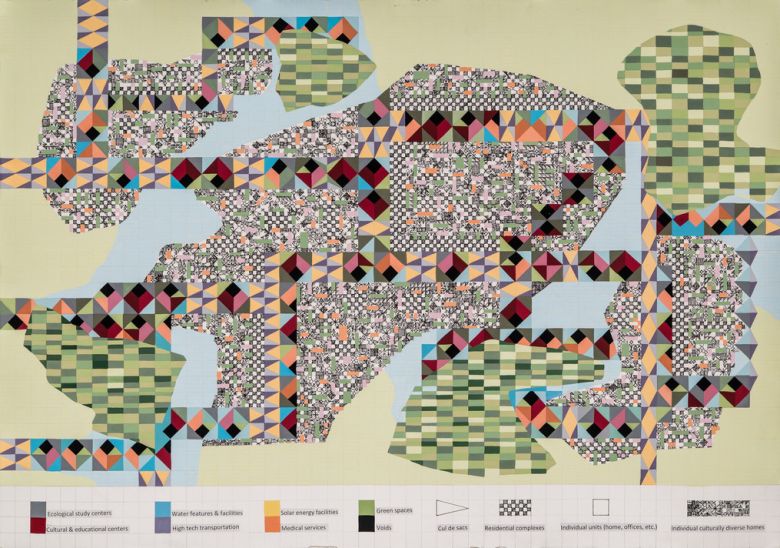

At first glance, Nargess Hashemi’s intricate, handcrafted, geometric paintings recall the elaborateness of Iranian miniature painting. We will soon find, however, that they are concerned with far more than just aesthetics. These patterns are in fact based on urban plans, and represent, in their own way, idealized cities conceived by the artist to offer a more sustainable, functional, and equitable future. The imagery is aimed at promoting social change and raising awareness of environmental degradation, particularly its impact on marginalized communities. Hashemi invites viewers to participate in the dream of more integrated, sustainable cities through her desire to create a parallel world with imaginary peaceful miniaturized heavens.

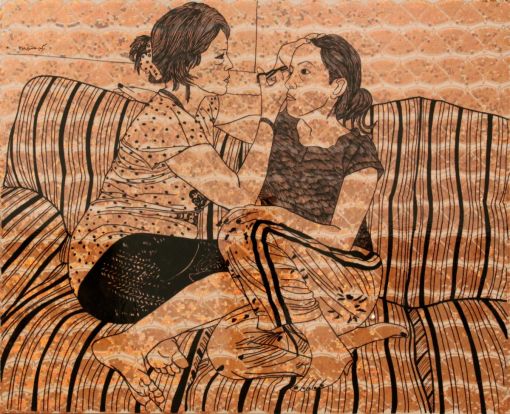

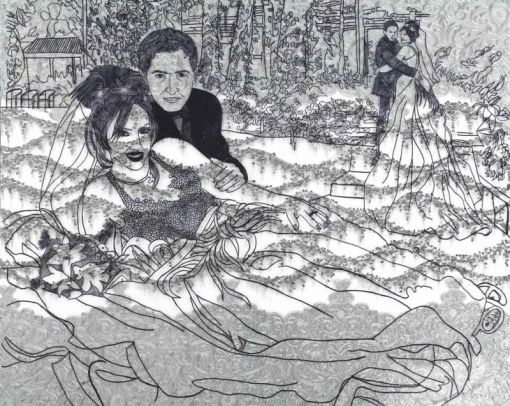

Since Hashemi’s early representational paintings of the 2000s, we encounter a gradual shift from figuration to geometric abstraction. Nonetheless, the artist’s central concerns and preoccupations remain the same: the interconnectedness of gender, nature, and social justice. In her most recent exhibitions at Gallery Isabelle van den Eynde in Dubai in 2018 and Homa Gallery in Tehran in 2023, Hashemi has developed her distinctive approach while references to her earlier works can still be seen: her sisters who she figuratively depicted in her previous paintings leave the frame and become collaborators, helping the artist make her new pieces. In a similar way, the everyday objects that previously appeared as layers in her work are now replaced by actual plastic water bottles turned into Eco-bricks.

As a contemporary textile artist, Hashemi’s ability to move freely between various mediums is evident in her installations. Her woven, handmade, blanket-like walls employ the same materials used predominantly by women for centuries to weave and plait objects and serve as a reminder of these traditions. Weaving dates back to the Neolithic era, making it one of the oldest crafts in the world. Women’s unique relationship with weaving goes deeper than the traditional production of clothes and furnishings for their households. Requiring patience and precision, this tactile craft from the very start of human culture illustrates the tension between order and chaos, embodied in the vertical warp threads and the horizontal weft threads that intersect at right angles. Before mass production, handicrafts were extremely valued. Created with utmost care and expert skill, these high-quality objects lasted a lifetime and preserved histories and cultures. In the era of mass manufacturing, the art of weaving has tended to be overlooked as a marginalized form of cultural production, traditionally falling outside the realm of so-called high art.

The separation of mind and body rooted in the ideas of Plato, led to hierarchical gender divisions, where women came to represent emotion, the body, matter, figuration, and the private realm, while men came to stand for creativity, mind, immateriality, abstraction, and the public sphere. As a result, women were relegated to the applied arts and men to the fine arts. Consequently, craft has historically been undervalued. In the 1970s, fine art’s hierarchies were challenged, and feminists in the 1980s questioned the importance of originality, individuality, and ingenuity in art-making and attempted to give primacy to objects linked to women’s experiences and the domestic sphere, thus paving the way for contemporary artists to experiment with weaving. A key example is The Dinner Party (1974–79) by artist Judy Chicago, which was made in collaboration with a number of women. Another example from the same period is Pattern and Decoration, a movement from the United States directed toward a critique of modernism’s rigidity. It sought to recover denigrated artistic forms as alternatives to the formalism advocated by art critic Clement Greenberg and others that was dominant at the time. Art critic Lucy Lippard observed that “the 1970s might not have been “pluralist” at all if women artists had not emerged during that decade to introduce the multicolored threads of female experience into the male fabric of modern art.”1 Artist Miriam Schapiro invented the term “femmage,” a combination of the words “female” and “image,” to describe her forceful visual works, which were rooted in traditional women’s craft techniques and paid homage to generations of anonymous women whose practices did not merit the attention of the art world.2

For Hashemi, it was her constant habit of doodling on pieces of paper that led to an important discovery. By drawing on the grid, over its obsessive structure of repetition, her works exceed its margins and subvert its logic of organization with their highly dominant circular shapes. For decades the grid had been everything. Literally everything was a grid in the aftermath of Minimalism! By replacing the grid, Hashemi’s quilts speak to women’s experiences. They represent connection, family, stability, and the creative spirit that has historically helped women overcome hardships. There is an insistence on building up a surface from thousands and thousands of tiny parts that is vastly different from the singular, stable forms of traditional sculpture. In the construction of Hashemi’s work, women’s bodies intimately engage with her organic materials.

Each square represents an individual unit. They are joined to form pieces that hang like curtains from the ceiling, spread across walls, or rise from the floor. These curtains invite us into the silent lives of women through the centuries. Entering any one of these works, we find ourselves in an open space sectioned off by delicate partitions made from large crochet pieces that provide privacy without fully separating us from others. These partially see-through curtains don’t cover or separate spaces but enhance their connection and interaction. They embrace one space without suffocating it and shelter another without completely concealing it. Representing the interior of Hashemi’s imaginary utopian homes, they play with ideas of visibility and invisibility. In all their charm and grandeur, they appear like suspended three-dimensional free-form paintings that have left their frames to reach the walls, floor, and ceiling.

In keeping with her ongoing interest in environmental concerns and for the sake of zero waste, Hashemi endows used materials with a recontextualized identity. Eco-bricks are a sustainable building solution that involves tightly packing plastic bottles with non-biodegradable waste materials so they can withstand pressure. Today, they are used as building blocks for various structures, such as furniture, walls, or even entire buildings. They also provide a practical solution for managing plastic waste and serve as a visual reminder of the importance of responsible waste management.

Sociologist Anthony Giddens believes that climate change is one of the most pressing issues facing humanity today. His idea of “life politics” emphasizes that individuals in modern society are increasingly engaged in decisions related to their own lives, such as lifestyle choices, relationships, and personal values.3 Therefore, sustainable development choices address the presence of women, who comprise half the global population, and their needs. Critiques of consumerism and investigating strategies for shifting its patterns has established a common ground for many women artists engaged in environmental politics. For these artists, art is not limited to individual makers but also extends to art collectives, as also witnessed in the history of feminism and stories of women’s friendships, a camaraderie where joy grounds a commitment to empowering each other through support networks. “What can I do for you?” — that’s feminism. And “what can I do for my surroundings?” — that’s humanism.

1 Lucy R. Lippard, “Sweeping Exchanges: The Contribution of Feminism to the Art of the 1970s,” Art Journal 40, nos. 1/2 (Fall/Winter 1980): 362.

2 Miriam Schapiro, “Waste Not/Want Not: Femmage,” in “Women’s Traditional Arts, The Politics of Aesthetics,” Heresies 1, no. 4 (Winter 1977–78): 66–69.

3 See Anthony Giddens, The Politics of Climate Change (Cambridge: Polity, 2009).

Nargess Hashemi, Sahar Samadian, “Femme/Terre/Égalité,” in mohit.art NOTES #7 (November 2023); published on www.mohit.art, October 27, 2023.