Over the last six months, together with sweeping changes in Iranian society and in the middle of the uprisings, an animal captured Iranians’ passion and imagination at a massive and unprecedented scale. Pirouz (in English, Victor), the only surviving cub of two Asiatic cheetahs named Iran and Firooz, was born in captivity on May 1, 2022, bringing a beam of hope to the project to protect this species, which is in extreme danger of extinction. He soon became a symbol of hope and endurance and found his way into the artworks of Iranian contemporary artists as well as graffiti artists. Pirouz’s name is mentioned, together with some other environmental issues, in the anthem “Baraye” (For, 2022) by Shervin Hajizadeh, which later was awarded Best Song for Social Change at the 2023 Grammy Awards:

For such polluted air

For Vali Asr [street] and its corroded trees

For Pirouz and his probable extinction

For the forbidden, innocent, [stray] dogs

As of the day that I am writing this text, Pirouz has died of kidney failure (on February 28, 2023), sending into mourning millions of Iranians who have seen their hopes, struggles, and combats in the mirror of his short life. Born to an Asiatic cheetah mother — symbolically named Iran — and nearly concomitant to the start of Iran’s liberation movement, Pirouz became a metaphor for Iranians’ aspiration for change, hope, and resistance. At this moment, Pirouz is certainly the most famous animal in Iran’s contemporary history, a fact that sends a clear message about people’s priorities to officials. His case is an interesting example of a change in the affective attitudes of this society toward animals, where biodiversity and animal rights have not been a substantial priority for a large part of the population. It clearly shows how a collective traumatic experience can fade the human/nonhuman dualism and help us see our similarities. Although the emotional response to Pirouz’s death and his symbolic status in relation to the protests overshadowed the danger of his species’ extinction in the headlines, the incident has nevertheless managed to affect the feelings and attitudes of a nation toward the other animals in general.

Slideshow, please wipe left:

Animals are integral to human imagination. They have been present in our visual imagery since prehistoric times and have been featured as protagonists in many of our global stories, myths, and folk tales. Animals are and have always been powerful metaphors, bearers of moral concepts, and allegorical substitutes for human beings. In fact, the personification of animals is so common that we automatically accept animals as symbols for human ideas, behaviors, and narratives.

Seeing animals in the mirror of culture is such a long-established habit that we barely notice how exclusively it shapes our understanding of animals. We commonly know animals through their various forms of representation rather than by direct experience. Therefore, it seems that culture does not allow us a direct encounter with animals. As the artist and art historian Steve Baker notes: “Any understanding of the animal, and of what the animal means to us, will be informed by and inseparable from our knowledge of its cultural representation. Culture shapes our reading of animals just as much as animals shape our reading of culture.”1

As the oldest subjects of visual art, the other animals continue to constitute a substantial part of all human image-making around the globe, and they still dominate in social media imagery, which engages a considerable amount of our time each day. However, visual representations always have “real world” consequences. Visual imagery has a direct role in shaping our mindsets, our preconceptions, and our sympathies, and so it inevitably determines the way we regard and interact with actual animals. Therefore, we know more now than ever before that we cannot separate the facts of cruelty to animals from their representation, just as we cannot ignore the role of culture in constructing the status quo when it comes to accelerating the climate crisis.

This explains the current increasing interest in animals in contemporary art practice as well as in art historical debates. The recent “animal turn” in the humanities encourages heightened attention to animals (or, as we’ve now learned to say: to the other animals). Although there are varied and complex motivations, the link to both the animal rights movement and to the accelerating environmental crisis of our time is undeniable.2 The animal turn invites us art historians to reframe our inquiry and to move beyond an exclusive concern for the human. It calls for new questions, out of sympathy and a sense of justice, which are more considerate about the actual lives of animals who exist outside the picture frame.

From a wider perspective, it seems that we have just noticed the degree to which the “animal” itself is a historically constituted concept. We have turned our attention to the homogenizing and marginalizing function of the single word under which we stack up millions of members of other species — or, in environmental scholar Una Chaudhuri’s words, the “epistemological morass to which we humans have exiled the other animals.”3 This long-standing crude dualism constitutes the grounds for much of our misinformation, prejudice, and ignorance about animals.

This shift in perspective has also brought about renewed attentiveness to art’s potential to raise awareness and compassion among audiences and to challenge the dominant ways of treating animals. Visual language not only tells us much about the diversity of shared experiences of humans and other animals but also makes it possible to imagine alternative ways of engaging with them. In recent years, the global contemporary art scene has witnessed various artistic strategies seeking to create alternatives to long-standing anthropocentric schemes and to reconfigure our relationships with nonhuman species.

In line with global changes regarding the human/nonhuman dichotomy, contemporary Iranian art has developed new approaches to conceptualizing animals. This goes hand in hand with Iranian artists’ significant move toward addressing ecological issues, as part of a wider cultural phenomenon that has its roots in multiple social and political factors. The emergence of post-revolutionary forms of environmental activism can be traced back to the early 1990s, nearly corresponding to the rise of global environmentalism. This occurred against a backdrop of overall public indifference to environmental issues, itself a consequence of the bad economic situation, eight years of war with Iraq (1980–88), and the reluctance of officials to inform and enlighten the public. Today, as headstrong industrialization, agricultural expansion, and privatization agendas increasingly lead to overgrazing, deforestation, lake depletion, and increased risk of species extinction, Iranians’ concern for raising awareness has become heightened, including among intellectuals, artists, and other cultural protagonists, who, like everyone else, are witnessing the immediate risks of the deterioration of nature.

Although this turn in public attitude toward environmental problems has considerably influenced the representation of the other animals in Iranian contemporary art, it cannot be considered the only source of the variety and popularity of their presence. Animals continue to play the role of our alter ego — they symbolize our pathos, misfortunes, and impasses, or they stand for our desires and aspirations.

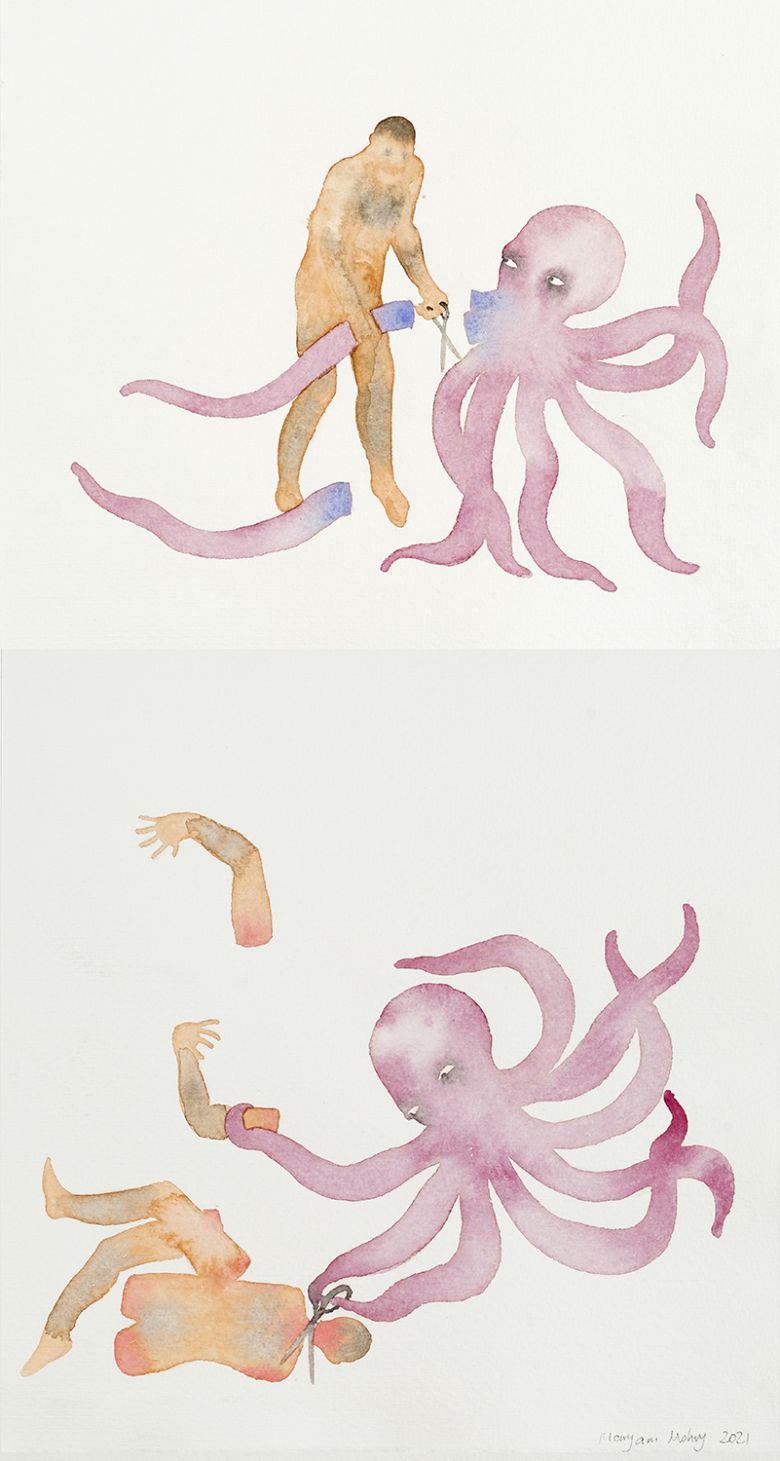

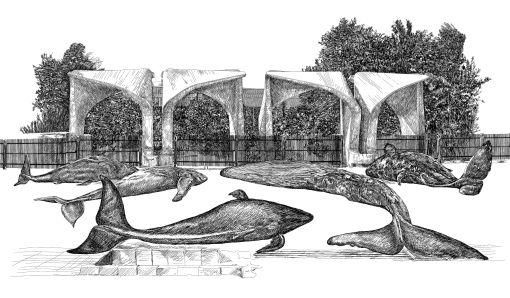

Some artists show profound empathetic and compassionate approaches toward the other animals as embodied and feeling beings, and have tried to immerse themselves and their bodily experience in the animals’ perspectives, in order to be able to experience the world as they do. The impressive video Road Kill (1998) by Bita Fayyazi, in which she buries sculptures of dead stray dogs, and the visceral, poignant realization of hungry and injured abandoned dogs by Tabib Aram in his series Outskirts (2017-21) offer two instances of this attitude. Other artists engage the representation of the other animals as metaphors for our social and political encounters: “Wherever I include an animal, it is in a conversation or identification with humans,” says Jinoos Taghizadeh,4 whose depictions of beached whales in various artistic media movingly evoke our persistent, painful national struggles for change. Maryam Mohri’s colorful, idiosyncratic illustrations of human-animal relations (The Choir Group in Party, 2023) touch our hearts, as her spirited, emancipatory images spring from her fantasies and begin bouncing and dancing in their fanciful worlds.

The following works are just a few representatives of the creative means by which Iranian contemporary artists are engaging with the idea of animality. Whether focusing on the animals themselves or representing them as allegories for our social experiences, these artworks are, I believe, examples of an encounter that might contribute to fading the human/animal boundaries. Each of these works is an endeavor to get outside our own human world and think and feel from other perspectives — which might set off our imaginations and make us take the other animals more seriously. They encourage us to reconfigure our attitudes toward our fellow habitants on this planet, feel their pathos, and ground our manners in moments of respect, care, and justice.

Bita Fayyazi’s project is one of the early examples of Iranian contemporary art to directly address issues of animal morality. She has continued to explore ecological issues in an intimate, expressive tone throughout her artistic career.

Pantea Rahmani’s drawings and sculptures of birds present a multilayered symbolism. They might be seen as an embodiment of her personal lived experience of meditation and the transcendental state she has long been practicing, including on her trips to India. However, her birds’ stark bodily injuries, scratched surfaces, and ripped-off skins ruthlessly remind us of the disastrous situation of both local and migrant birds in various parts of Iran. They are an eloquent illustration of how these creatures essential to Iranian historical, mythical, and environmental consciousness have come to occupy a marginalized and vulnerable place in our world, destroyed in massive measures.

Bears and snakes dance, jump, and merge into humans in the colorful fantasy world of Maryam Mohry. “Dancing, excitement, messing around—all I like to do and am banned from doing, I do it in the skin of these animals,” explains the artist, who has sensed herself to be an animal since childhood. Her concern for the destruction of animals’ habitats and the cruel fate humans are forcing them to face is reflected in her charming, affectionate illustrations of animals, which aim to emotionally engage humans and trigger them to change the status quo. The close relationship between humans and nonhumans in her work goes so far as to result in sexual intimacy or merging into one another.

It has been nearly a decade since whales first captured Jinoos Taghizadeh’s imagination and began appearing in her artistic practice in various forms. The “52-hertz whale” is an individual whale who calls at an unusually high frequency compared to whale species of its type. This is why she cannot be heard by her fellow species members or other sea dwellers. The artist considers this lonely giant as an allegory of artists and intellectuals, who typically live a lonely life, as few others understand them. Her miserable beached whales symbolize the pains and efforts of a nation paying an enormous price for change.

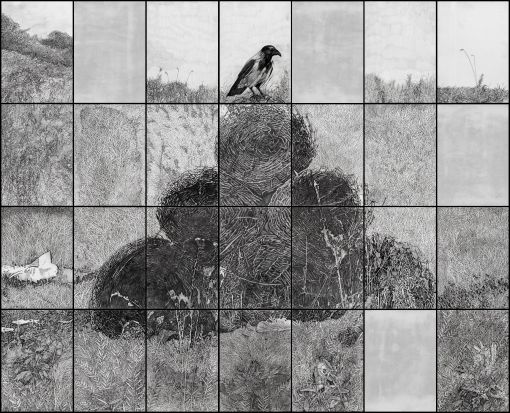

Gol-o-Morgh (Flower and Nightingale) is a classical Iranian painting motif that refers to an ideal state of lovemaking between the flower and the nightingale, an allegory of beauty, eternal love, and peace. In Niloofar Kasbi’s incredibly intricate drawings, this traditional motif takes on malignant facets: harassment, injustice, and deteriorating nature. In Niloofar Kasbi’s depictions of “liminal spaces,” including large swaths of land that fall between major cities, we see marginal places in “nature” manipulated to such a degree that it is no longer natural, nor, in the hands of human, properly taken care of. The crow symbolizes a common, unglamorous bird that is incredibly resilient and can endure harsh habitats. Kasbi’s crow might be seen as an allegory of the artist and her generation, who were brought up to cope with various problems and insufficiencies.

Nazar Mousavinia’s highly detailed figurative paintings show humans and other animals in close, though eerie, relationships. This work references the idea of Renaissance landscape, from the cold mountains and foggy backgrounds in Masaccio’s frescoes to the strange backdrops of Leonardo DaVinci’s paintings. The birth of the notion of “landscape” is concomitant to its being exploited and constructed, both in intellectual and practical ways.

1 Steve Baker, Picturing the Beast, Animals, Identity, and Representation (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1993).

2 Una Chaudhuri, “Introduction: Animal Acts for Changing Times, 2.0: A Field Guide to Interspecies Performance,” in Animal Acts: Performing Species Today, ed. Una Chaudhuri and Holly Hughes (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2014), p. 1.

3 Ibid. p. 8.

4 Jinoos Taghizadeh, interview by the author, June 14, 2022.

Helia Darabi, “For Pirouz and His Probable Extinction,” in mohit.art NOTES #1 (April 2023); published on www.mohit.art, March 24, 2023.