Imagine an old man trying to hold on to his reality. As I write this, Hanging On by Vivian Withers is playing in my head. He wakes up in the middle of the night, goes to the drawer, searches through stacks of papers and takes out a dozen books he hid years ago. Loss of memory defies the sequential order of time. Suddenly he takes the books to the most secluded part of the house, along with the transcriptions, and hides them in an incision between an old fuel tank and the basement ceiling. It’s a picture I’ve had in my head since I found a stash of books at my parents’ house in 2019.

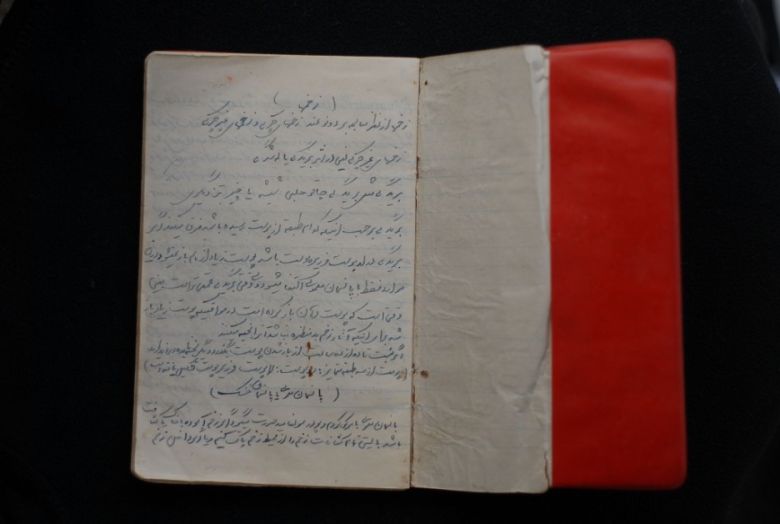

Among the papers, there were Marxist books and memoirs, but the most important one was a red notebook. It may bring the myths of communism; it is visually appealing like from another time. It took me on a journey to my father’s life in his 20s-30s, when he was a political prisoner in Qasr prison in the 1950s.

The notebook is full of specific information on body structure and first aid measures. The text was interesting in terms of the types of physical problems it contained, most of which are quite outdated, but accurately described in terms of symptoms and cures. My father hid his notebook from himself, fearing the surveillance that his past reminded him of. The record of a study group kept by prisoners in Qasr Prison in the 1950s is mixed here with oral recollections I heard from my father, which make up the first part of this booklet.

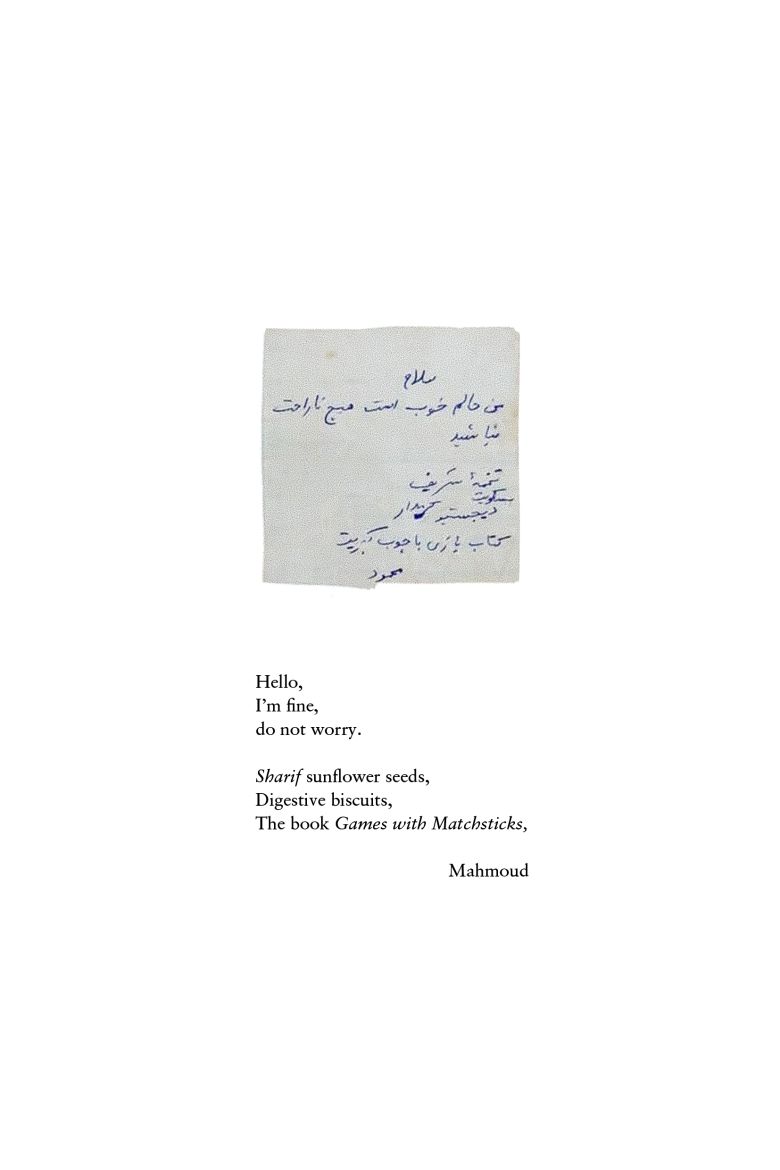

The second part begins with an excerpt from a letter by a political prisoner from the post-1979 period, a time that is an ordeal in the collective memory of Iranians, full of mass arrests and executions, especially against the generation that enabled the revolution against the monarch. One ruler has been replaced by another, for whom politically active youths have been and will continue to be a serious threat — and are often locked in prisons.

In this letter, an excerpt of which I have included here, a prisoner writes a short note to his family asking for some groceries and a book called: Games with Matches. I asked my friend to find this book for me. It seems to be quite rare and hard to find in the market anymore.

My friend found it for me on Revolution Street, in a big book market in the center of Tehran.

This was a translation originally published in English as Tricks, Games And Puzzles with Matches written by Maxey Brooke. It was published in the 1970s in Iran and was apparently popular in prison. I am curious if the author has imagined the possibilities of his book and taking on its significance. What but geometric figures and matches could be more eloquent in prison? The divisions of ideas, spaces, bodies in which they would see themselves and mathematical puzzles with a (possible) solution to revise them all, at least for a short while, in their heads, on a piece of paper or on the concrete of their cell. By removing the matches and changing the structure, one cell disappears, removing another and only two squares remain.

There is a whole chapter in the notebook on burns, their depth and the types of blisters and skin indicating depending on the severity of the burn. Blisters should be protected and cared for until they heal, as they protect the wound from infection. The preoccupation with the fragility of life and the self-education about the marks and cuts on the skin that heal over time may stem from a strong desire to one day live unscathed. On the other hand a scar is a sign of an ordeal that one can be proud of if one manages to survive it.

In Persian, Qasr means palace and is a historic complex in Tehran. The former Qajar palace – in the past resplendent with the beauty of gardens full of birds, later converted into a prison by Russian architect Nikolai Markov and used as the main detention center for political prisoners from 1929 – was transformed in 2012 into a museum of Islamic revolt.

Evin is the name of a quiet village located in Shemiran district in the north and northwest of Tehran. Well known for its nice weather and beautiful hills, a big part of this village is now dedicated to this notorious prison, which gradually overshadowed Qasr. The site has been the main detention center for political prisoners in Iran for the past 50 years.

The two prisons in question are a complete oxymoron, both in terms of the implication they bear (Evin and Qasr / palace and village), including the contrast with the beauty of their surroundings. Ruin, which is perhaps an inversion of this oxymoron, makes me think of the inmates who keep playing the matchstick puzzles over and over. The bird sings and pulls the prisoner out of the cell to communicate, to be present as a voice that travels. I remember a friend’s recollection of his personal experience at Evin, when the voice of crows inspired him to begin communicating with a prisoner from a neighboring cell using tap code messages. The moment when your tongue fails you, but you hold on to prison walls, hoping that something from the outside might hold your hand, only for a brief moment, because you must stick to the rules. Not rules that are dictated to you, but new ways of communication.

There are three of my recordings that I want to attach here, three personal takes on this subject.

Neither Aleph Nor Lam, a piece written two years ago as an 8-channel composition, combines some words from the notebook and searches between the lines for a secret message to be conveyed in a voice that has been enslaved by the insatiable power that listens. The original site-specific composition was aimed at making space transparent by bringing in the sounds of the surroundings. Parallel to the idea of the notebook to heal and save the body I connected the tap code messages of the notebook to the drumming of the woodpeckers. They cannot sing in the conventional sense, but they are the carpenters, musicians and healers in the forest ecosystem.

The second piece is entitled The Poet’s Ear. It is based on a recording I made in the Ear of Dionysus (Orecchio di Dionisio), a limestone cave on Temenites Hill in the Sicilian city of Syracuse, known for its acoustic phenomenon. Its name, given by the painter Caravaggio, probably comes from the similarity of the entrance to the shape of a human ear as well as its unusual cavernous acoustic properties. Legend has it that Dionysus, the tyrant of Syracuse, passionately eavesdropped on his prisoners through the opening of the ‘ear’. A darker version of the story says that Dionysus carved the cave to amplify the screams of the tortured prisoners. The menacing silence of the Ear of Dionysus is reminiscent of muffled voices, whose murmurs can grow into roars in the empty space of this man-made cave.

The final piece, Windrum, is a recording of the wind pounding out a rhythm from the loose bars of the prison fence. The former Bourbon prison in Syracuse, Sicily, is located by the sea, abandoned after the 1990 earthquake. The view can be enjoyed from the outside, as the battered bars win a tribute to the sea. It reminds of Sheikh Imam’s song El Bahr Beyeddhak Leih, which asks why the sea is laughing.

Images, text, and audios courtesy of the artist.

Sarvenaz Mostofey, “Pecking Wood, 2022,” in mohit.art NOTES #6 (October 2023); published on www.mohit.art, September 14, 2023.