For the second issue of the mohit.art NOTES editorial theme “Space,” for which I have been kindly invited as a guest editor, the online exhibition A Space of One’s Own brings together collections of artworks that share two subjects: space and imagined futures.

Even though the space considered in these works corresponds primarily to the definition of physical space, their portrayal of what we could call “an imagination of the future” is capable of transforming and changing our relationship to this physical space: a search for the in-between spaces in time and space. At times, the imagination of future in some works manifests itself as an impulse leading to change, transformation, and development, and at other times in other works, it is the reason for a silence, idleness, forgetfulness, or lack. Time plays a crucial role in this imagining. In some works, the imagination of the future is not only rooted in the past but also traceable in future. How does time breach its bounds, and how can that imagined future in that future time become possible? How does time define and demarcate our relationship to space? How do temporal changes transform or redefine this relationship? Conversely, how does the experience of a certain space change our relationship to time? And, finally, how might temporal and spatial transformations change our epistemic relation to time and space, or at least interfere in it?

The six artworks presented in the online exhibition A Space of One’s Own present to us the human Lebenswelt, or “living space,” in various time periods and geographies scattered around the world. The lives of people within societies have always been influenced by the architectural features of space in different eras, the urban constructions of metropolises, and the political and social conditions that influence both internal displacement and immigration, migration, and so on. Although the subjects of the presented artworks are various, sometimes divergent, and certainly more expansive than can be explored here, they converge in this exhibition due to their shared concern with the above-described issues.

The project Suburban Hauntology (2022) by Arash Hanaei encompasses digital designs, installation, videos, and holograms, which together create a constellation of reality and imagination, sitting somewhere between these two. The artist based the digital designs on photos of Parisian suburbs that he either took himself or found during his research.

In the video Unblocked Avatars (2022), Hanaei focuses on the famous residential building Ivry-sur-Seine in Paris, designed by French architect Jean Renaudie in the 1970s. Two avatars discuss the necessities, potentials, and requirements of designing the building. The conversation takes place in the metaverse, giving the viewer the impression that it is happening both in the past and in the future. It is as though Ivry’s building is haunted by ghosts from the metaverse and is being studied as an experiment on the possible distributions of space in the future. In recent years, Hanaei has been focusing on the suburbs and margins of cities. Taking inspiration from cultural theorist Mark Fisher’s idea of “hauntology,’ the artist reconstructs the marginal and suburban spaces in the timeless and spaceless world of the metaverse, using the potentials of augmented reality to challenge the utopian ideas of 1970s architecture.

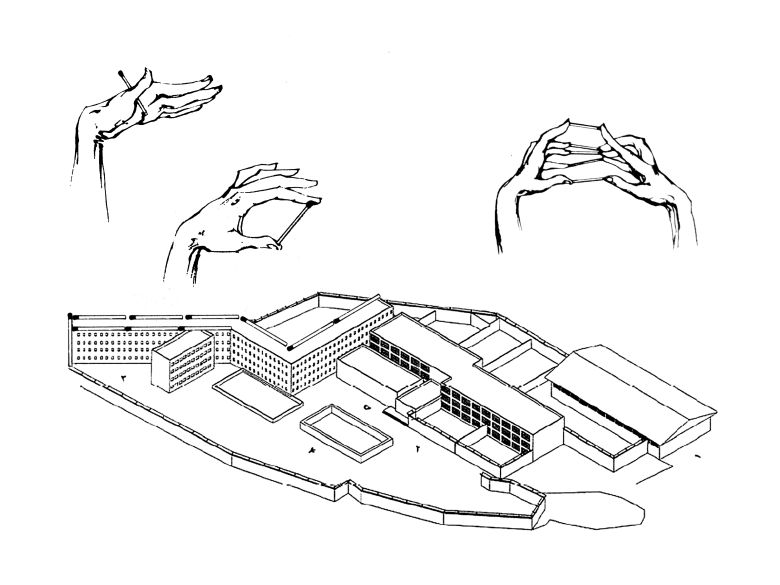

Bahar Noorizadeh takes the 1920s avant-garde architecture of Russia as well as architects’ designs for “disurbanization” as her point of departure. In the video The Red City of the Planet of Capitalism (2021), the artist presents architectural designs of the era while reading a letter by Mikhail Okhitovich, an avant-garde Russian architect, to Le Corbusier, a modernist Swiss-French architect. In The Red City of the Planet of Capitalism, Noorizadeh uses 3D designs to combine the aesthetics of 1920s Russian architecture with visual forms similar to those found in computer games, creating a connection between sketches almost a century old and a possible future world, mixing sound, text, and narration.

Time in Noorizadeh’s works is an ongoing stream. The buildings we see are based on ideas and schemes of the past, and yet it is as if they come from the future. As if we have been placed in a time machine and put on a nonlinear road where different times become interwoven and mixed together. Despite the fact that Okhitovich’s letter to Le Corbusier is a sharp critique of the latter’s ideas of modern urban construction, the imagery and sonorous space created by Noorizadeh playfully mixes reality and imagination, leaving us amid quotations from Vladimir Lenin, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, in waves of colour, light, and sound.

Noorizadeh traces the idea of “disurbanism” promoted and developed by Okhitovich and his contemporaries, who aimed to expand on the communist ideas circulating in the Soviet Union in 1929. And this year, 1929, is the very same year that the Russian architect Nikolaï Markov transforms a Qajar palace into Iran’s first modern prison. It is here that the imprisoned poet Mohammad Farrokhi Yazdi inscribes on the walls: Oh you, the stone-hearted fortress Qajar Palace … And it is precisely from this place that another artist, Sarvenaz Mostofey departs on the artistic journey for her work Pecking Wood (2021). Mostofey also took inspiration from a personal story: finding her father’s prison notes from his years at Qasr Prison in Tehran, in which she encounters notes mainly circling around methods for self-preservation and survival under the prison’s harsh conditions. From these, she has created an audio work that magically interweaves past, present, and future through sound.

The project also includes a leaflet by Mostofey, in which, besides explaining how the sound works were created, she builds a narrative bridge between Qasr Prison before the 1979 Revolution and Evin Prison after the Revolution. The latter part combines time and space. And it is here that we read part of a note by a Evin prisoner in which, among other things, he asks his family to send him a book. This book opens a window to a game: a game with matches, a game for change, for escape, for freedom. In Mostofey’s works, space is represented through words and sounds. Imagination plays a key role here — both for understanding how a work of sound art can represent a certain spatial and temporal condition and for obtaining a clearer image of what has been happening to the narrators of the story within the prison cell.

Migration and displacement are further key themes explored in the current exhibition and it is the primary subject of Behnam Sadighi’s ongoing series The Last Day (2010–). Here, the artist photographs Iranians on their last day in the country before emigrating. He takes the photos on the morning of the final day, in front of the person’s last residence, surrounded by everything they are about to take with them. We are faced with photographs that interweave different layers of time and space simultaneously. In the present moment of taking the photo, both past and future occur concurrently. The fact that we know that this is the last picture of this person in their homeland transforms the image into an image from the past. And yet, since we also know that this person is leaving their home for another place where lies the hope for a better life, this imagined future builds a bridge from past and present into the future.

The spaces captured in the photos contribute to the formation of such a multilayered condition. What we see here in this part of the Lebenswelt of the photographed people — a narrow slice of a street, and a city in a country that the subject is about to leave behind. The information provided as an appendix to the photographs gives us an idea of where the person is heading to; thus we can also imagine this future place. Each of Sadighi’s images contains different temporal and spatial codes. Ultimately, however, the photo in front of us is the registering of a condition, a historical condition. The last day of registering a dystopian condition filled with hopes of reaching a utopia.

The travelers in the photo series The Last Day have now arrived at their destinations, lived there for some time, experienced a few things, made their own space — and yet they are dreaming of a place that is different from where they live. It might be a place in the past or in future. Portraying a similar transitional space, Pegah Keshmirshekan’s video installation Imaginary Homeland (2023) drops us into a nonlinear conversation between the artist and a London bus driver

Partial images and voices eventually give us a more coherent perspective on the subject of the conversation as well as the interlocutors themselves. We realize that we are observing part of the life of an Iranian migrant who has spent most of her life in London, and yet her imaginary homeland is somewhere outside her current time and space. Migration not only changes individuals’ geographical location but also transforms their reflective and mental lives; therefore, the experience of migration disturbs temporal and spatial relations in the life of a migrant and changes the meanings of both.

Demolishing buildings, buying waste (2017) by Nazgol Ansarinia could be considered as a fitting end to the exhibition. In the work, which consists of several parts, a space is demolished to make way for a better building — a new space based on an imagination of the future. However, it seems that all this effort could be in vain: the cycle of demolition never ends. Focusing on the so-called urban construction projects that Tehran has been undergoing for years, Ansarinia observes — closely and very precisely — the process of demolishing a residential building in the city. Then, by putting these pieces back together, she tries to make something different out of the demolished building’s parts. What she makes by juxtaposing sketches, sculptures, and videos in the series is, in fact, the image of absence. It is as if we are searching among layers and in between the pieces of iron and cement for the memories of a time and a space that no longer exist.

In addition to this online exhibition, these works by Hanaei, Keshmirshekan, Mostofey, and Noorizadeh will be on display at Schwaben-Bräu-Passagen in Bad Cannstatt, Stuttgart, in the frame of the festival CURRENT – Art and Public Space, from September 21 to 24, 2023. On September 21, mohit.art will host an artist talk with Hanaei, Keshmirshekan, and Noorizadeh, and exhibition curator Zohreh Deldadeh, on site in Stuttgart, which will also be live streamed on www.mohit.art.

Translated from Farsi by Golnar Narimani

Please have a look at our Calendar, where we announce current exhibitions and events by artists from Iran and other art scenes in Westasia with each issue of mohit.art NOTES.

Zohreh Deldadeh, “A Space of One’s Own: Editorial,” mohit.art NOTES #6 (October 2023); published on www.mohit.art, September 14, 2023.