In a culture living under Sharia law, contemporary Iran is a place where any articulation of desire beyond religious jurisdiction is incredibly risky and could lead to hazardous consequences. It is widely known that Sharia is a system with a particularly strict juridical focus on the regulation of sexuality and codes of dress (especially with regard to women), the prohibition of alcohol, dancing, and music, and the meticulous censorship of representations of sex and the nude body in art and media. The implementation of Sharia is the Iranian state’s mode of articulating its self-definition as an Islamic Republic both to its own nation and to the external world.

The idea of lust — “havas” in Farsi — is perhaps the primary mechanism that drives Sharia in Iran and elsewhere. Havas is the enemy, the most radical form of otherness, but, most importantly, it is an enemy that lurks within and that constantly threatens the stability of the self. The powerful psychophysiological link between sense stimuli and human sexual arousal is the main reason why, in a Sharia world, danger exists around every corner of the subject’s field of vision. With increasing technological sophistication, the Iranian government’s shaping and control of visual and performance culture is one of the defining features of contemporary, mass-mediated life in Iran.

Havas has become a threat that is always present in the Iranian visual economy, making this economy inherently unstable and vulnerable, in need of vigilant policing and protection. The central aim of government censors and the Amniat Akhlaghi (or morality police) is to eradicate from the entire society any sense stimuli or substance that could be a possible source of or conduit for lustful temptation — for example, all images of sex, eroticism, and improperly clad bodies; all forms of narcotic indulgence; all expressions of dance and song. Havas is such an unpredictable and insidious enemy that “self-control” (whatever this means) can never be enough. Censorship of the entire external world is necessary to stave off its corrupting impulses. Moreover, in a society where the subject is presumed to be male and the matrix of cultural intelligibility fundamentally heteronormative, the main targets of this form of state surveillance and corrective justice are, unsurprisingly, women.

How do contemporary artists in Iran grapple with, on the one hand, havas as a human experience and, on the other, the practical impossibility of pornographic image and sound? How do they go about showing us a worldview in which lust (with its many putative discontents) is an ever present danger, one that threatens the stability and integrity of anything one sees or experiences? How do they introduce us to the “enemy within,” articulate the existential threat it poses, and illustrate its place within the symbolic structures around them? And how do they go about conversing with this enemy and translating its peculiar language, affect, and mannerisms?

The extremely dangerous tendency of the female body to be or to become pornographic necessitates the mandatory wearing of a hijab and of clothing that conceals the physical contours and details of the body. It even necessitates a ban on women singing, as the female voice is seen as a potential weapon of seduction. The very notion of feminism and female empowerment is anathema to Sharia because such political goals are seen as providing women with the power and agency to be sexually tempting and thus a corrupting influence on society as a whole. Furthermore, the fundamental irrationality presumed by patriarchal power to be an essential feature of the feminine (just as it has been in Western cultural traditions) means that women are fundamentally incapable of self-management, and so where havas is concerned, they are loose cannons in the sociocultural landscape. Similarly, the global LGBTQ+ movement is seen as nothing more than havas masquerading as a human right.

Iran defines itself geopolitically in extreme opposition to countries where it believes havas has run amok, countries where the general atmosphere of permissibility believed to be characteristic of liberal democracy has produced cultures in which lust is given free license to infect all rational systems of law and governance and to there recreate Western civilization in its own image. This strategy of a self-constitutive negation of havas is evident in the words of the former president of Iran, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, who famously declared in 2007 at a forum in New York City when pressed on Iran’s imposition of the death penalty on homosexuals: “In Iran, we don’t have homosexuals like in your country. In Iran, we do not have this phenomenon. I don’t know who has told you we have that.”

So, how does one articulate in any medium a desire that cannot be articulated? How does one think about a thing that is unthinkable? Contemporary art and its curation may be one of the best ways to approach such questions. Contemporary art as a discourse continues to be enriched by its seemingly limitless and ever multiplying methodological pathways to express the inexpressible, through the myriad rhetorical devices and conceptual ruses available to artists in their quest to document and analyze all facets of the human condition. Despite the obvious limitations placed on what the artist is allowed to do and say in Iran, Iranian artists are masters at employing whatever tools are at their disposal to penetrate the forbidden realm of the erotic just enough to feel its electric charge and return to tell the tale. Havas is manifested through the cracks and apertures opened up by contemporary artists in Iran who develop highly innovative means of confronting the enemy within, entering into productive exchange with it, tarrying with it, embracing it, or simply laughing it to shame. The artists whose work will be explored here never break the strict rules imposed by the state because they simply cannot afford to do so, but also because they do not have to.

In the Iranian context, lust is almost unrepresentable by way of figurative art; however, abstraction opens up numerous possibilities for artists to produce works that give some degree of shape and intelligibility to this forbidden feeling. More importantly, abstraction provides so many pathways to interpretation and misinterpretation, so many semantic detours and dead ends, that a work dealing with the power of the erotic can and often does successfully bypass the systems of surveillance and censorship that threaten its very existence. Abstraction is ideally suited to the difficult task of detecting and capturing the experiential traces, intensities, and subcutaneous pulses of what we might call erotic desire, but without ever fully bringing it into view. The work of AX is one such example.

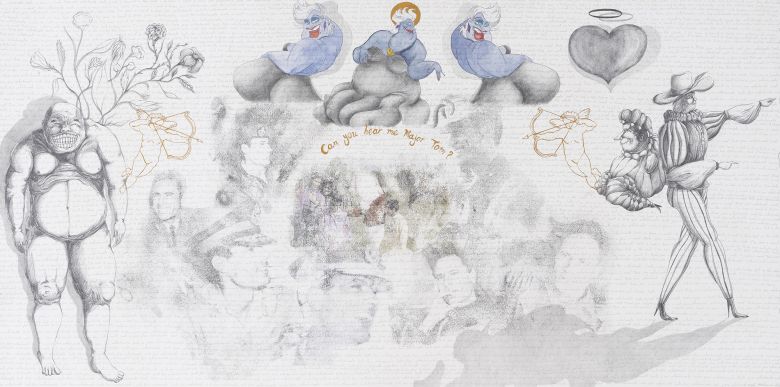

Even in the area of figurative art, Iranian contemporary artists may depict lust using various strategies of evasion, some old and some new. The heavy use of symbolism, metaphor, and amphibology to express desire has deep roots in classical Persian art and literature. These strategies endure in present-day Iran, where, for example, lust can be framed or represented in the metaphorical guise of an ideological foe. The fact that the Iranian state defines itself and the nation in such stark and strict opposition to havas means that artists like NM can effectively deploy the visual language of the carnivalesque and the gothic monstrosity to put a face or — even better — a mask on havas that makes it immediately recognizable as an external enemy. In this way, her figurative representation of lust is aggressively politicized in visual form to the extent that it not only becomes passable to government censors but also communicates what can be easily construed as an alignment with the government’s ideological conception of the external world. But, then again, could this be an instance of amphibology?

Finally, humor is another very fruitful method of approaching lust. Laughter can diffuse almost any tense situation. The deft use of prank comedy to recast havas, the enemy within, as a hapless, clumsy fool of a friend is the strategy employed by S R, video artist and filmmaker. Her work proves that calculated risks are always possible when employing humor as a discursive device, given the fact that it has a unique ability to be disruptive and recuperative, and is often both at the same time. In S R’s work, as with the work of many other Iranian contemporary artists, havas is balanced on a razor’s edge between comedic disruption and moral recuperation, allowing the threat of havas to surface, albeit briefly, in the work, before being eventually sublimated into raucous self-deprecation.

While much can and has been said about the issue of censorship in present-day Iran, and while it may be true that a whole dimension of human experience — erotic desire — remains effectively off-limits to artists living in Iran, it would be remiss not to turn a critical eye on the global art world outside Iran. The art world and its market demands are driven by a white, Eurocentric, liberal-democratic consciousness that, if philosopher Michel Foucault is to be believed, has been locked since the Victorian era in a discursive paradigm that views erotic expressivity as the ultimate articulation of personal and political liberation. As the global art market trades in contemporary artefacts of increasing economic and symbolic capital, it continues to place inordinate value on shock tactics and frontal assault as the hallmarks of artistic heroism. Artists who inhabit non-Western worlds and their diasporas — who live in places and contexts where the risk of producing confrontational work may, for one reason or another, far outweigh the benefits of heroism or even martyrdom — have the same right as any to have their work assessed in a way that is acutely sensitive to their particular conditions of existence as artists and not to be limited in their production by standards narrowly defined according to the ideals of Western popular progressivism. What is more, it is intellectual laziness to rely on shock and pornography as the primary mechanisms of intervention in the ancient and ongoing discourse on lust as a human experience.

For security reasons, some names have been changed and abbreviated.

Lester Wishart and M KH, “Havas: Desire as Lust,” mohit.art NOTES #4/5 (August/September 2023); published on www.mohit.art, July 28, 2023.