While figurative art has obvious drawbacks regarding how far an artist in Iran can take depictions of sexual desire, abstraction can present possibilities, however slight, for presenting the pornographic. In the series of paintings in ink and acrylic entitled Freedom (2017), AX depicts ambiguous human silhouettes painted in vaguely suggestive poses. The figures are abstracted by way of aggressive color and crosshatching, resulting in a scenography that situates them in what appears to be a phantasmatic dimension whose erotic charge and intensity can never fully break through into the realm of the visually perceptible.

The paintings give one the distinct impression that what is being witnessed cannot possibly be romantic or playful eroticism. The environments in which these figures appear are similarly ambiguous. It is often difficult to ascertain whether these bodies are experiencing pleasure or pain, whether they are in heaven or hell. One cannot fully determine if these moments of what seems to be erotic charge and physical connection are taking place under conditions of freedom or incarceration.

The style of painting makes it easy to imagine this vision of havas (or, in the artist’s words, “freedom”) as apocalyptic, as a cautionary tale — not unlike many of those contained in religious texts such as the Bible and the Qu’ran — that violently illustrates the persistence of perversion when the world burns. This work, moreover, places the viewer in a state of suspension at the uncomfortable yet strangely stimulating intersection of fear and desire.

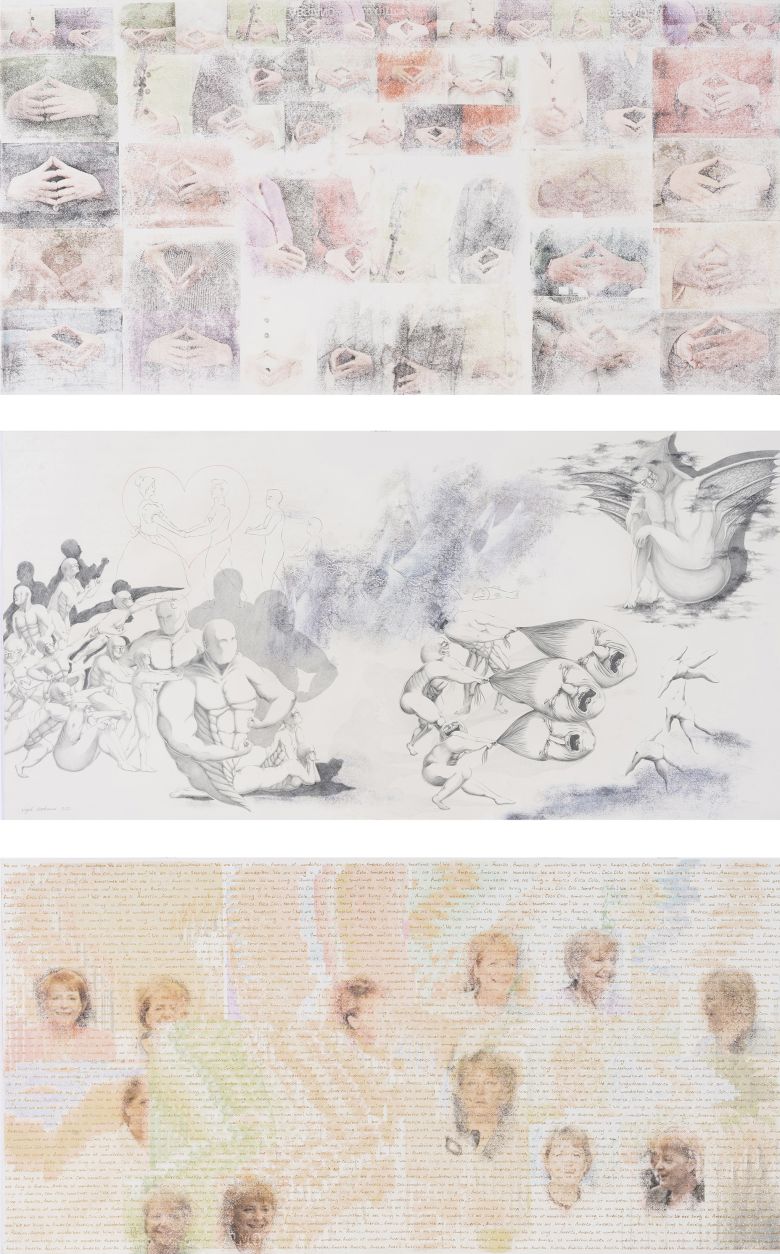

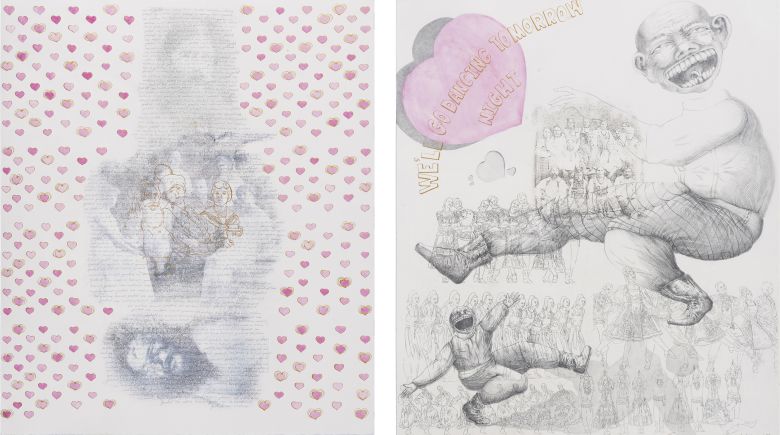

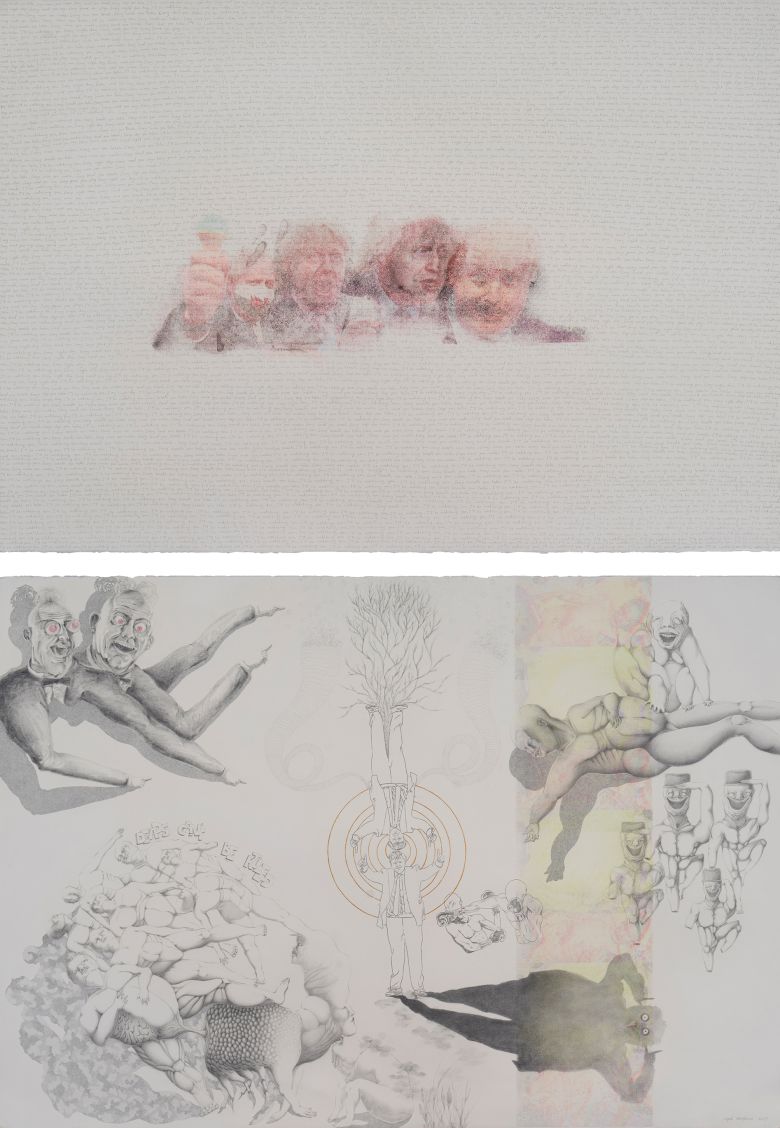

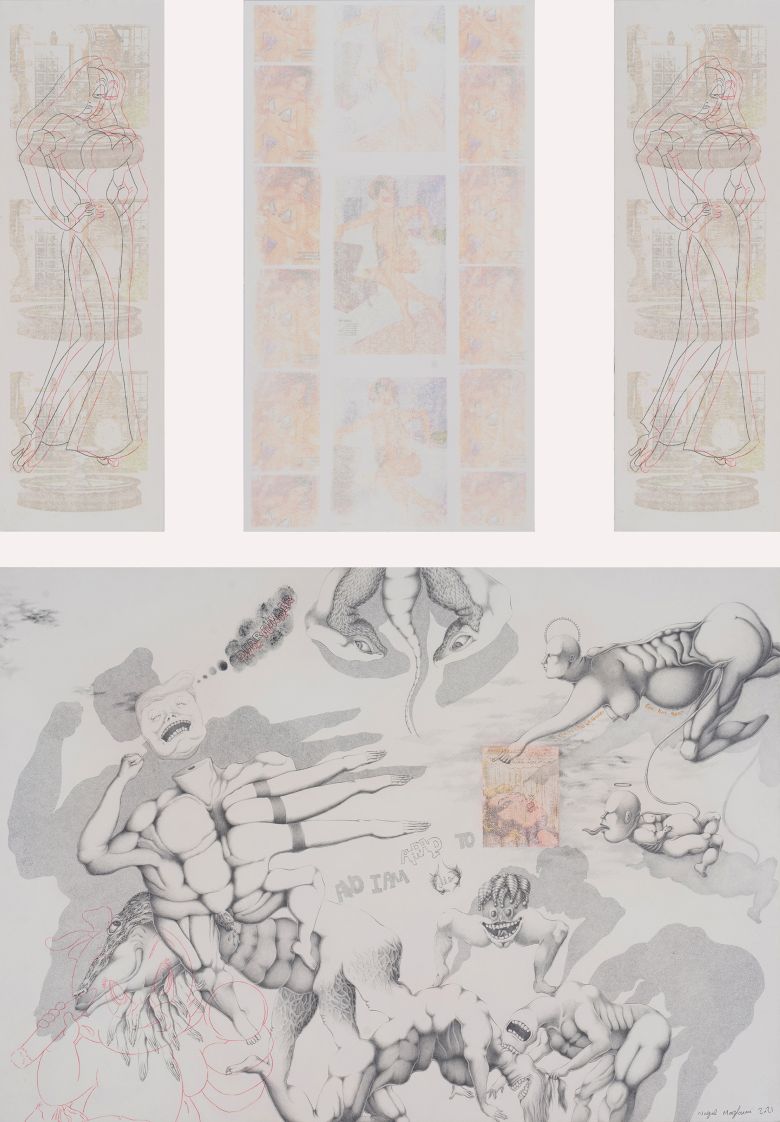

In the mixed-media series Harsh Reality, or What We Do Not Speak Of (2022), artist NM makes an explicit link between Iran’s ideological self-definition and its oppositional politics of havas. What makes this work a particularly skillful means of engaging with the idea of lust in a highly fraught and censorial context is the artist’s transposition of the “enemy” from within to without. In a rapidly globalizing world that is increasingly shaped by various brands of hard and soft power, Iran’s ongoing project of clerical nationalism relies heavily on the mobilization and weaponization of havas as the essential and defining characteristic of the external enemy.

According to the artist, the idea for the series originated in a desire to visualize “politicians’ bodies and ‘the body’ in politics, the manifestation of these organs, and the circumstances affecting or restricting them.” She continues: “As I move forward, this idea expands and turns into a game which is not limited to the bodies but [also includes] the positions and relationships that exist in the politics as well.”

The artist’s words only hint at what seems to be a nightmarish vision lifted directly from the pages of Sam Huntington’s sociopolitical thesis Clash of Civilizations — a picture of the diseased global “body politic” that emerges out of global capitalism, celebrity culture, and the spread and entrenchment of Western values across the world. The artist lets us gaze through the eyes of the Iranian state at the world outside, and what we see is a comically grotesque inversion of the infamous “axis of evil” trope coined by US President George W. Bush over two decades ago. In these works, the body politic birthed by globalization is the exact embodiment of havas, cast in the form of the gothic and the carnivalesque: hideous, bloated, leering caricatures composed among faded images of famous world leaders and other political figures at the height of their powers — Barack Obama, Angela Merkel, Donald Trump, Vladimir Putin, Grigori Rasputin, Boris Johnson, Muammar Gaddafi. This pantheon of political pinups collectively transmits an exuberant and seductive combination of youth, sexuality, and power.

Strategically positioned on the canvas are various icons of mass-mobilized desire and consumption, most notably the archvillain Ursula from Disney’s 1989 animated feature The Little Mermaid. That the series was created only a year before Disney’s much ballyhooed worldwide release of a live-action version of the film, with an African American woman playing the lead role (bringing with it the charge, leveled by right-wing media commentators and netizens, that Western identity politics is itself a regime of censorship), cannot be mere coincidence. Lyrics from Western pop hits like Wham!’s “Wake Me Up Before You Go-Go” and David Bowie’s “Space Oddity” provide even more semiotic clues toward an understanding of these works as complex and highly stylized representations of global hard and soft power hopelessly corrupted by culturally sanctioned frivolity, excess, and extreme individualism.

S R’s video installation Lida (2002) is an excellent example of an artist’s successful use of humor to stage a brief brush with havas. In this piece, the artist plays a prank on the spectator that illustrates how easily the human mind can succumb to the primal power of the pornographic image. In fact, the results of her comedic experiment may be evidence that there are moments of precise duration when havas precedes rationality in the ever unfolding constitution of the subject through time.

[Spoiler alert!]

The video begins with a close-up of what appears to be a gaping orifice surrounded by pale, pink skin. It is impossible to detect whether the skin belongs to a human or an animal. As a viewer, you cannot wait for the camera to reveal enough visual data to precisely confirm the ontological status of what you are seeing; your mind races through the possible categories into which you can fit this increasingly intriguing thing on the screen. As the camera slowly zooms out, the orifice shrinks in size, but there is only more and more skin. A rational mind, capable of fending off the sudden and sometimes embarrassing attacks of havas, would observe dispassionately and wait for the facts before arriving at a conclusion. Instead, havas invades your impatient mind.

At what point do your faculties of visual perception, conceptualization, and organization finally kick in and your gaze “correct” itself? How long does it take for you to realize that what you have been seeing all along is the distended navel of a pregnant woman? When does it dawn on you that only a perverted mind would ever think otherwise, one whose visual impulses are primed for the pornographic?

The prank the artist plays on the spectator relies heavily on the radical separation of the spheres of motherhood and sexuality that is a common feature of patriarchal cultures all around the world — a fact that makes the work universal. But as a tongue-in-cheek feminist intervention, it is all the more effective because the prank itself is a performative mockery of the very idea of the male gaze, which, half a century ago, became a core concept in psychoanalytic feminism and art theory. The end of the video makes it clear that this was not a baseless attempt to force you into a shocking or traumatic encounter with the enemy within but rather a means of revealing the enemy while successfully mitigating its pornographic power through self-deprecating laughter.

With an air of smug intentionality, the faceless woman closes a pair of black curtains, leaving you giggling in embarrassment at the close proximity of your baser instincts. The artist’s joke is on you. Your shame is your punishment for having such a filthy mind, for having such impatient, uncontrollable havas.

For security reasons, some names have been changed and abbreviated.

Lester Wishart and M KH, “Havas: Desire as Lust Image Essay,” mohit.art NOTES #4/5 (August/September 2023); published on www.mohit.art, July 28, 2023.