What is at stake is not conservation of the past but the fulfillment of past hopes.

— Max Horkheimer and Theodor W. Adorno, Dialectic of Enlightenment

Historicism in Iranian architecture was, until recently, characterized by identity and authenticity. Even what historian Kenneth Frampton defined as “critical regionalism,”1 where traditional architecture and modern approaches were combined in an effort to protect local spaces, was a minor resistance to the generalizing forces of modernism. Nationalistic or civilizational propaganda through holistic revivalism and metaphorical and semantic references to history would define historicism in Iranian architecture. Therefore, national or cultural identity, holism, and resistance became the general characteristics of these historicist movements. Architecture reproduces history through its universalizing perspective, which in Iran created a distinctive yet modern architecture. However, through this generalization, historical forms become points of value in themselves instead of having any contextual or situational practical value. Compared to such identity-seeking and national approaches, in recent years, something different has been happening in Iran. In short, history is no longer a general point of reference but a channel through which the new and the contemporary can be redefined.

Architecture in general has become excessively situational or contextual.2 It aims for boldness in its singular and contingent appearance. However, this contingency does not mean resistance to global or universal trends. An amalgamation of the two without a leveling of particularities happens. Here, particular histories become channels for an alternative translation of contemporary problems. In fact, “history” finds its true definition as the “realm of particularities”3 — a translation of the universal into contingent spaces. “Concrete universality” or individuality as the true form of universality could be the real spirit of this trend. Histories are read through personal narratives, not as a negation of universal forces but in order to translate them into infinite singular situations. Narrative environment, as a tool for giving holistic stories to heterogeneous forces, makes a unique architectural setting.

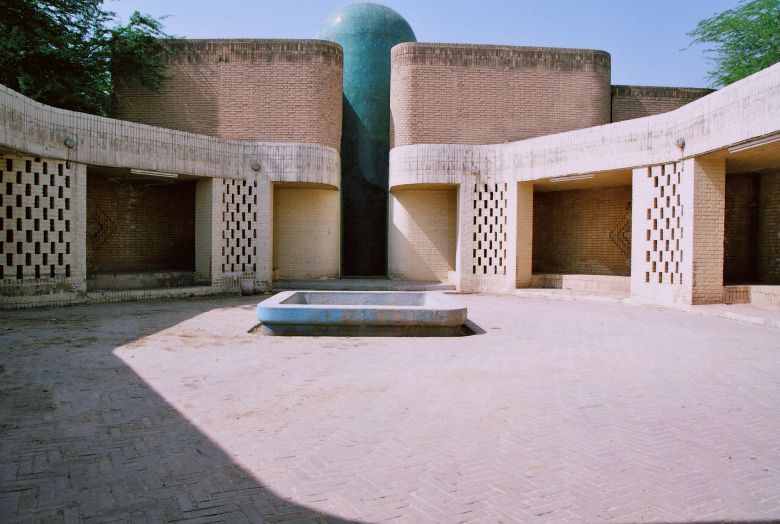

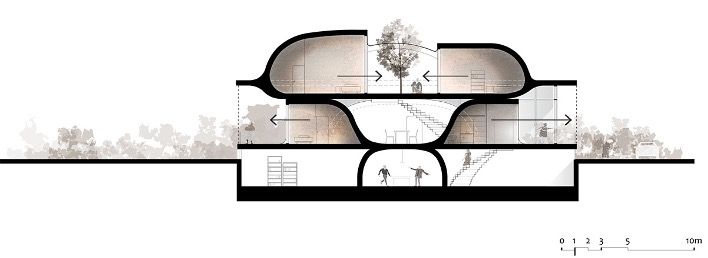

There are traces of this symbiosis in contemporary Iranian architecture. Alireza Taghaboni takes certain dualities in traditional Iranian architecture and translates them into a contemporary setting. He compares the precise geometry found in courtly architecture with the fluid forms of folk mudbrick structures to create a new aesthetic based on tectonics or modes of construction. In the Guyim Vault House, crude brick vaults and a glass cube create a dichotomy between regional and universal, modern forms. The semi-open spaces of the vaults resemble traditional iwan,4 while the building’s set-like design, which places the brick vaults inside a modern glass cube, produces an inside-outside tension. For Sadra Civic Center, a project proposed for a residential quarter in the suburb of Shiraz, the open, negative space of the courtyard becomes the primary space, while closed spaces are shaped around it. Here, the hierarchy of open and closed space, negative and positive, is reversed.

In both these projects, one thing is clear: Taghaboni is not concerned with historical national identity or a resistance to history. Instead, historical references serve as a channel to open up space for alternatives. When I speak of alternatives, I don’t mean yet another aesthetic trend but a deeper need for revising architecture’s relation to the social and natural environment.

These historical references are not Iranian or Islamic per se, but a partial and contextual reinterpretation of them. History without any concern for authenticity is reinvented into an architecture that is contemporary in every possible sense. For example, a school designed by Arash Ali-Abadi and Daaz Office in the Sistan and Baluchestan province, a deprived region in southeastern Iran, has a twofold purpose, bringing together in one setting a publicly accessible space and a school. In addition, local methods of construction are used, not to revive a bygone world but to create a new ambience and life using pragmatic means. In another example, by ZAV Architects, a mudbrick arena in Hormuz translates a semi-Greco-Roman amphitheater into a platform to watch the sea from while creating an unofficial public space and a square for nearby cafés and cultural centers. Past and future, the local and the universal, are brought together through creative architectural narratives — not unlike experimental movies, where a distance from commercial film creates new possibilities, which must wait for a conscious re-reading of them in order to produce alternatives for mainstream cinema.

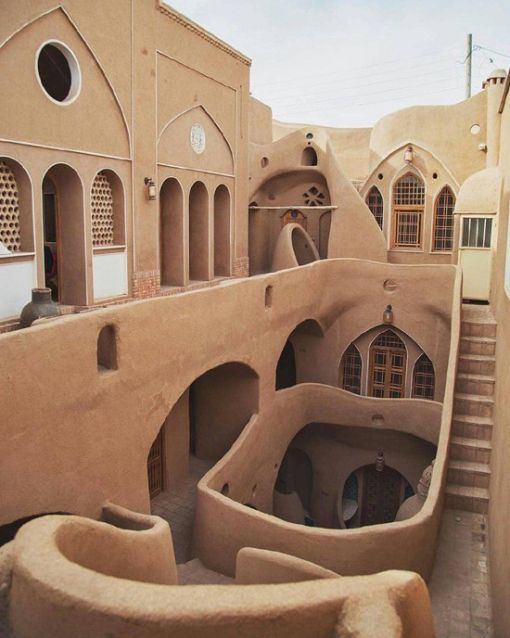

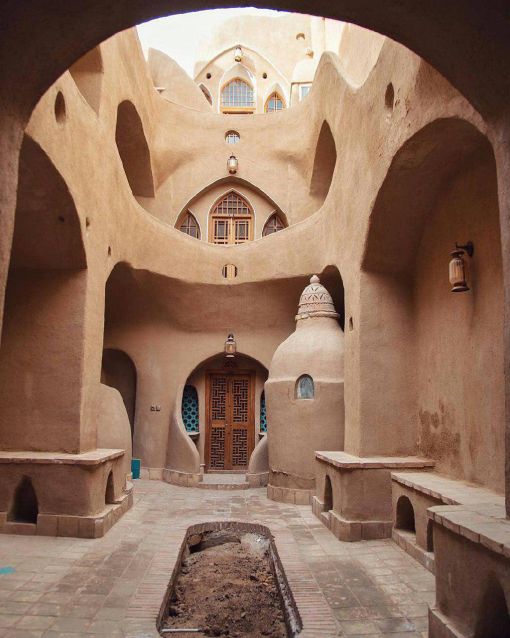

An ideal setting for these architectural projects, which stand out from the generalizing forces of urban life and capital, are historical urban fabrics. In these contexts, the duality of preservation and development is fertile for new dialects. The Sang-e-Siah (black stone) boutique hotel in Shiraz integrates old alleys, brick constructions, and a courtyard into a contemporary gallery and hotel. Its architect, Stak Office, did not try to make the building look authentic but saw the context as an opportunity for reinventing common perceptions of contemporary space. This new tendency is even traceable in renovation projects. Where laws and regulations permit, rather than reproducing historical kitsch, history becomes a basis for creating new ambiances of form and function. The reconstruction of Akhavan House in Kashan took the fluid form of mudbrick walls to an extreme, merging it with geometric motifs from traditional Iranian architecture. It appears as if the material is set free from the outer constraints of geometry and finds an inner and organic form.

There is a common trend in all these architectural projects and it is their performance toward earth. The Farsi word for “digging” (kandan) is the root word for “home” (khaneh).5 In addition, “khaneh” is the general suffix for “place.” This etymological link between “digging” and “place” has remained in the subconscious of traditional Iranian architecture. Earth is not a natural (in the sense of generally being exterior to cultural space) and neutral platform for architecture; in fact, the buildings give birth through its womb. It was commonly accepted in traditional Iranian architecture that the best way of constructing a house was to use mudbricks made of soil from the site. Home expands from out of the earth. Philosopher Seyyed Hossein Nasr describes this as a cyclical process, where traditional Iranian cities that rose from the earth returned to it once abandoned.6 Underground spaces, in all their variations, like godal-baghcheh (underground garden), sardab (underground water chamber), and many others, are (as psychoanalyst Carl Jung might have put it) the subconscious of this architecture. Once again, contemporary Iranian architecture tries to readjust its relationship to the environment, and specifically to the earth, beyond being one of boxes on a flat ground. This return to Mother Earth, or to put it better, this inception from the earth itself, is a symbol of the efforts for a coming future in which, once again, architecture seeks to balance its relation to nature. One of the major aspects of these historicisms — these sciences of particularities — is the critical reproach of modern trends in architecture that defied human dominion over nature but not with or through it. This is a materialist history rather than an idealist one. Nature, and earth in particular, is the necessary precondition of this architectural phronesis.

These revisions, on the one hand, distance the present and the future from false universals and fetishes and, on the other hand, release history from nostalgia and national or civilizational identity discourses. Without restricting particularities in a closed regional or national space, they directly translate universals into singularities — this is the true interpretation of architectural “concrete universals.” They help to create a third space of universal particulars, a merging without resistance. In this sense, the postmodern notion of culture as minor incommensurable differences loses its meaning. Culture also is no longer separate from nature but works through it, surpassing the modern-era’s false perception of culture as outside of nature. Reaching a new understanding of the relationship between culture and nature is the logic behind the revision of history in contemporary architectural projects, which show traces of an earthlier future. “The future is already here,”7 yet, the fragile traces of an emancipatory space promised by these examples of contemporary Iranian architecture need to be brought into the light of consciousness in order to keep lost hopes alive.

1 See Kenneth Frampton, “Towards a Critical Regionalism: Six Points for an Architecture of Resistance,” 1983, modernindenver.com (accessed June 17, 2023).

2 “The theory of architecture no longer exists, the theory of each project replaced it.” Translated from French. See: Guiheux, Alain, Le Grand Space Commun (Genève: Métis Presses, 2016), page 13.

3 See Beiser, Frederick C., The German Historicist Tradition (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), p. 214.

4 An iwan is a deep portal, not just an entrance but a central living space in traditional Iranian architecture. In the char-soffeh, four iwan inwardly face one another to form a central domed atrium, and in the kushk (garden kiosk), four iwan face outward. Taghaboni has stacked three inward-facing iwans and three outward-facing iwans on top of each other.

5 See the entry for the word khaneh (in Farsi) in Encyclopedia of the World of Islam, rch.ac.ir (accessed June 28, 2023).

6 “The Islamic town rises gently from the earth, makes maximum use of nature’s own resources and when abandoned usually returns again gently to the bosom of the earth.” See Seyyed Hossein Nasr, Islamic Art and Spirituality (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1987), p. 57.

7 “The future is already here — it’s just not very evenly distributed.” William Gibson, “The Science in Science Fiction,” Talk of the Nation, NPR, November 30, 1999.

Saeid Khaghani, “History as an Alternative Future,” mohit.art NOTES #3 (July 2023); published on www.mohit.art, June 30, 2023.