For me, a migrant, the forgotten words are always those that emerge in the future — perhaps — in hope.

Ever since I became an immigrant, I’ve felt an odd affinity with linguists — or more precisely, translators who are familiar with the intricacies of language. At times, I get so lost in words and signs that I end up cursing myself out. When you’re a migrant, you’re constantly shifting between two languages. And by language, I don’t just mean the systems of alphabets and grammar we use to communicate. I mean a system of signs — the kind semioticians refer to when they talk about a “language system.” Like I said, ever since I became an immigrant, I’ve started to feel like a linguist myself. I’ve spent so much time balancing between two systems — two worlds and a double consciousness: the one I came from and the one I’ve migrated into — so much that I’ve forgotten how to think or speak naturally.

Playing with language, in language, and between languages is a full-time occupation for any migrant. And it’s not limited to crossing national borders; even moving from one city to another within the same country — as in my case — roots this act of translation deep inside you. It clings to you like an inescapable obligation. It’s as if you’re perpetually caught in a comparative flux between the world you left behind and the one you now inhabit. In this liminal space, you are compelled to continuously translate — cultural values, social norms, behavioral patterns, the entire cognitive framework of each place, along with the memories forged within these two distinct worlds, among other things — from one mode of consciousness to another.

Now, as I sit here trying to write about “home,” watch what this simple word does to my weary migrant mind. Right now, I want to play with language so you can really get a sense of how deeply migrants wrestle with it. Some of you might get bored, so here’s an alternative: you can skip certain parts of the text if you want. Honestly, I wouldn’t blame you.

But to sum up what I want to say at this point: as an immigrant, when I think about belonging and try to make it part of my reality, another element always seems to enter the picture: hope. To me, we migrants can only truly belong to a place, a thing, or a person if hope lives in our hearts, because belonging is fragile and can vanish in an instant. So there has to be something that, when belonging slips away, can bring it back, restore it, and rebuild it — and that something is hope. The relationship between hope and belonging is, of course, a strange and complex one — and trying to find a balance between the two is a Herculean task. You’ll come to see this for yourself as we move forward.

Before I even begin to adopt the poetic tone I want when speaking about home, language first pulls me aside, whispering meanings I can’t ignore. That is, before I dive into the heart of the matter — before I explain how I try to forge a sense of belonging to the home I grew up in by clutching onto hope and gazing at my childhood home, or, more broadly, by gazing at the diaspora — I first set out to show that there in fact exists a semantic, linguistically rooted connection between the words “hope,” “belonging,” and “looking.” Perhaps in doing so, I aim to ease my anxiety about language itself. As if, once again, by tracing a thread among these three words, I’m able to translate them into one another, so I don’t risk neglecting the migrant’s eternal duty: translation.

Now, if you’re not up for following this thread, feel free to skip ahead a few paragraphs to the section marked with a ***.

For those of you who have chosen to stay with me here, in the intricates of language and translation, I should say that when the name of home is spoken, the first word that lights up in my mind is “belonging”: the sense of belonging, and how this feeling engages various qualities of the migrant’s emotions, affections, and thoughts. Belonging, even when expressed in its nominal forms — belonging and belongingness — retains the performative quality of a verb through the “-ing” suffix, signaling not only action but temporal continuity. The verb’s reliance on the preposition “to” further underscores its directional nature: belonging always implies movement toward, an inclination, an extension. It is not static but sustained — its presence must be continually enacted. The word’s synonymy with terms like “attachment,” “clinging,” and “devotion” points to its affective and relational intensity.

Hope is conceptually entangled with belonging. Like belonging, it is future-oriented and relational—it reaches toward what is not yet. The lexical field of hope includes terms such as “expectancy,” “dream,” and “prospect,” emphasizing anticipation and emotional investment. Semantically, hope implies both desire and belief in fulfillment, anchoring it in both feeling and cognition. Its conceptual structure is linked to vision: to hope is to look — to watch for what might come.

The eye, as a sensory organ, mediates between interiority and exteriority. It enables contact while preserving distance — an essential condition for reflective engagement. Vision fosters affinity and attachment, paralleling the mechanisms of belonging. The eye’s outward reach, its gesture of extension, mirrors the temporal and affective dynamics of both hope and belonging, turning sight into a form of relational movement.

As you see, through these outward movements — extension, expectation, attachment — belonging, hope, and the act of looking become intertwined, forming a profound and resonant bond with one another.

Now that things between me and language have softened a bit, I’m ready to immerse us once again in the poetic tone that opened this photo-essay.

***

It has been nearly seventeen years since I left home. And ever since, I’ve found myself clinging to a fading sense of belonging — as if holding it tightly might prevent it from slipping away entirely. With each return — those rare, widening intervals — I’ve come to believe that, for someone like me, the architecture of belonging can be reconstructed only through hope. A quiet hope: the sort that flickers in the gaze of a bystander, or sometimes a voyeur, who stares unrelentingly at a home they can no longer fully enter. I live in the extension found within the three acts of hoping, looking, and belonging. With hope in my heart, I continue to observe, striving to still belong. To belong to the home, I gaze upon it, piece by piece. Not once, not twice, but countless times — always. The home, it seems, is the very assemblage of my gaze; it is the culmination of my thoughts. No matter how often I look, it never protests. My gaze toward the home extends me, stretches me, pulls me — pulls me toward belonging. Oh, how I wish it would pull!

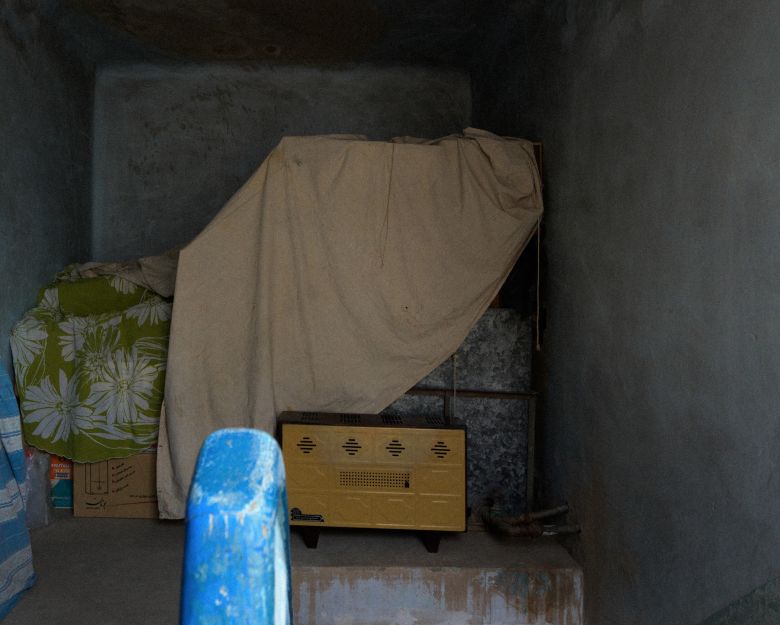

Each time I revisit home, I find myself absorbed by familiar corners, silently watching, whispering, I will be thinking of you with words I’ve forgotten. Belonging is a past perfect I alchemize into a present perfect. I gaze at the fading wear on the wooden door of the living room with words I’ve forgotten. I think of the soft shadows in Mom and Dad’s room with words I’ve forgotten. I think now, I think last year, I think at fourteen — all at once, in a continuous thread of time. With words I’ve forgotten, I gaze at the blue of the stair rail. Now, the sole of my foot brushes the crack between the tiles in the room just off the kitchen — with words I’ve forgotten. On March 26, 2019, my foot touches the crack between the kitchen tiles — with words I’ve forgotten. Now, at thirty-six, now, at twenty-eight, now, on January 28, 2016, now, at five years old, one summer afternoon, I tug at a loose thread in the moquette — just enough, with forgotten words, so Mom wouldn’t notice the growing tear. With words I’ve lost, I pull the small rug over it. With words I’ve forgotten, I hide beneath the stairs, and with words I’ve forgotten, I wonder if pressing my face to the cool pink tiles might make the summer heat a little easier to bear. With words I’ve forgotten, I read the spines of the encyclopedias on the bookshelf; I read them now, I read them three years ago, I read them at seven, climbing a stool, sounding out the letters of words I can’t yet read. With words I’ve forgotten, I press my index finger into the cracks of the bookshelf until the mark stays on my skin. With words I’ve forgotten, I crouch behind the door, peeking into books meant for grown-ups. With words I’ve forgotten, I recall the feet that once moved up and down these stairs in my memory; they do not appear.

These forgotten words are the lost language of belonging — of all the loosened threads that once bound me to the home of my childhood. These “words” are not mere vocabulary lost to time; they are not even words in the literal sense. They are metaphoric situations: embodied fragments of relation, atmosphere, and ritual — codes of presence and absence, the shifting signs through which the home once spoke to me. They held its power structure, its rhythms, its silences. They are the invisible grammar of belonging, a language etched not in alphabet but in gestures, glances, floor cracks, and forgotten rituals. To lose these words is to lose the familiar syntax of the home’s lived reality, leaving me to translate anew a place I thought I knew. That home is no longer what it once was. Perhaps it still stands where it always did, but seen through that mental frame I’ve always carried with me — dragging my wandering self from place to place — it changes each time. Circumstances have changed. Now, home has become my Other. But, still, it is within that impossibility — thinking with words that have slipped away — that I imagine belonging might ever begin to take shape again. Even if belonging, for immigrants, may never be fully realized, the yearning for it burns so fiercely that hope becomes an inevitable companion. Hope and belonging wrestle constantly — antagonists and collaborators in equal measure — as if by their struggle alone, something might be built again from what’s been left. It is in this very friction, in this irreconcilable but generative tension, that the immigrant lives; and that I live.

And I, amid contradictions, pass through again and again. The former belonging, that sweet belonging, the one you thought would never fade away, can no longer be rebuilt. The sense of belonging is like a slippery, sudsy bar of soap — just when you think you have it in your grasp, it slips through your fingers, shooting out and leaping beyond your hands. Between hope and the sense of belonging, there is a perpetual oscillation, a kind of synthesis. In fact, these two are in a constant tug-of-war. The sense of belonging, if it exists, is ultimately a construct. When you leave a place, it ceases to be yours. To dwell again in a home, a third language is required: a language that is neither the language of the home nor the language of the place you have immigrated to. To approach that home, I can no longer step toward it with the eyes of my former self. I have changed, and so has the home. Now, whenever I glance at or muse upon that house, I do so through the shadow of all the days I’ve been absent. And this, precisely, demands another kind of knowing: a third language born of absence and longing — a language that reads not only the spatial transformations of the home but also the altered choreography of human relations within it. The silent codes of intimacy, memory, and care have shifted; their meanings are no longer fixed but performative, elusive. To dwell in this reconfigured space — both bodily and affectively — requires a language attuned to the fragile textures of present experience, a language that resists the weight of inherited grammar and instead speaks in whispers of change and becoming. In this third language, without style, in a primitive manner — just as I don’t know what to do with “the blue I-beams” — I am always uncertain, fumbling in search of building a new home that will let me settle and through which I can come to know myself. For this reason, I do not rebuild the home; rather, I construct it anew, from the ground up.