Content

Notes #14

Ghubar Islamic Art Studies is a research group based in Iran that serves as a dynamic platform dedicated to the study of Islamic art history and its historiography.1 The disciplinary formation and evolution of Islamic art studies is shaped by an amalgamation of cultural, political, and intellectual currents, both within Iran and beyond, particularly in Europe. Western interest in Islamic art history surged in the nineteenth century as European colonial forces approached the Islamic world through the othering lens of Orientalism, portraying and conceptualizing Islamic culture — and consequently Islamic art and material culture — as a foreign, monolithic, exotic, and ahistorical. The early works of the Orientalists are marked by a focus on the arts of the Arab world and the characterization of Islamic art as overly ornamental and decorative.

Early scholars such as Alois Riegl and Ernst Kühnel emphasized decorative elements like arabesques, geometric motifs, and calligraphy in Islamic art, interpreting them as lacking naturalism or narrative depth when compared to European traditions.2 The portrayal of iconic sites like the Alhambra in Spain and Cairo’s mosques often focused on their visual ornamentation rather than their cultural significance. These European figures among many other, while preserving valuable historical images, framed Islamic art through a Eurocentric lens that highlighted its aesthetic “otherness.”3

Archaeological explorations of the Middle Eastern region in the late nineteenth century played a crucial role in shifting the scholarly perspective on Islamic art, distancing it somewhat from the confines of Orientalist and ornamental views. This sparked new interest in Islamic art history and the expansion of the evolving field into the art of the Persianate world, exemplified by the 1910 exhibition Meisterwerke muhammedanischer Kunst (Masterpieces of Muhammadan Art) in Munich. Although this monumental exhibition primarily framed Islamic art in terms of decontextualized aesthetic qualities, it marked a turning point by including objects from non-Arabic-speaking regions of the Muslim world. It caused a surge of interest in collecting and writing about Persian art, as seen in the works of a generation of scholars, including the American art historian and advocate for Persian art Arthur Upham Pope (1881–1969). This unprecedented diversification of the field broadened perspectives and introduced Islamic art as a significant source of artistic and scholarly inspiration.4

Although universities and museums — most notably the University of Tehran and the National Museum of Iran — were established around the 1930s as part of state-sponsored modernization initiatives, it took decades for art history to enter Iranian academia. This formative period is marked by the dominance of the ahistorical views of the so-called traditionalists about Islamic art, rooted in the ideas of thinkers such as Seyyed Hossein Nasr (b. 1933) who assumed an ahistorical, spiritual essence of Islamic art.

Around the same time, scholars in many Western (particularly North American) institutions began focusing their work on the genuine incorporation of Islamic art into the narratives of world art history. Among them were Oleg Grabar (1929–2011) and Sheila Blair (b. 1948), who approached Islamic art within its diverse and multifaceted temporal, social, and cultural contexts. Grabar explored its evolution through pre-Islamic influences and societal needs, while Blair highlighted its diversity across regions, shaped by local materials and patronage. This group of art historians were vocal critics of the traditionalist view, arguing that scholars like Nasr, by idealizing Islamic art through an ahistorical, mystical lens, undermined the historical reality of Islamic art as a dynamic response to an ever-changing culture.

Although the field of Islamic art is now evolving worldwide through the interdisciplinary perspectives of transcultural, postcolonial, and feminist studies,5 mainstream academic spaces in Iran are still dominated by traditionalist approaches. Even when new art history curricula were designed in the 2010s, this essentialist viewpoint persisted, and students were mainly encouraged to use comparative methods to “analyze the evolution of global Islamic art in order to understand and uncover its Islamic essence and aesthetic qualities.” For decades, Islamic art studies in Iran have adhered to traditional, often uncritical frameworks.

Out of a necessity to create an alternative space for Persian-speaking scholars and art enthusiasts, Ghubar emerged as a groundbreaking, grassroots initiative in the winter of 2021 in Tehran, with the aim to provide opportunities to rethink and write about Islamic art within a globally connected, scholarly network. Unlike the conventional, often uncritical approaches fueled by ideological motivations that are common in Iran, Ghubar introduces fresh, historically grounded perspectives that align with contemporary global methodologies. Ghubar bridges the divide between Iranian researchers and the broader international scholarly community. It facilitates critical explorations of Islamic art, emphasizing the diversity and richness of Iranian and Islamic artistic heritage and supporting a new generation of scholars with a voice that is both modern and authentic. By integrating critical approaches, including transculturalism and interdisciplinarity, it offers Iranian researchers and students fresh perspectives developed elsewhere while also introducing the works of Iranian scholars to a broader international audience.

Ghubar offers a range of educational resources designed to expand the horizons of Iranian scholars. By promoting new books, research, and methodologies aligned with international trends, Ghubar aims to cultivate a community of students equipped with the critical skills needed to engage with Islamic art from a multidimensional perspective. These resources include online courses, research publications, and collaborations with international scholars. Due to the restrictive nature of the official academic environment in Iran, which often sidelines historical approaches, Ghubar has focused on creating alternative spaces for discourse through online platforms such as its website, Instagram, and Telegram, which are widely popular in the country.

In addition to its online presence, Ghubar organizes impactful in-person events, such as the lecture series “The Art and Architecture of Isfahan: A New Narrative” held in Tehran on November 13, 2023, featuring leading scholars presenting their latest research on Isfahan; and the “Idea of the Just Ruler” lectures on April 23–24, 2024, which brought together international scholars and was attended by more than eighty participants.

The platform also provides a much-needed counterpoint to Eurocentric perspectives and the remnants of Orientalist approaches that have historically dominated Islamic art studies in the West. By emphasizing critical engagement, Ghubar empowers Iranian scholars to reclaim their narratives, presenting Islamic art in a way that is sensitive to local contexts and resonates globally. This underscores the belief that the cultural history of every region is deeply rooted in its land and is tied to the social dynamics and unique perceptions that arise from within the communities there. These internal perspectives carry nuances, traditions, and meanings that are often lost or misinterpreted when viewed through an outside lens. This comprehensive approach fosters a new generation of Iranian art historians informed by global trends but grounded in a nuanced understanding of Iran’s rich artistic heritage, aligning Ghubar with the contemporary movement in Islamic art historiography that advocates for diversified, inclusive, and postcolonial perspectives.

Ghubar carefully selects from a diverse and expansive array of materials to conduct analyses on the historiography of Islamic art. By engaging with these varied materials, Ghubar explores how Islamic art has been interpreted, documented, and contextualized over time.

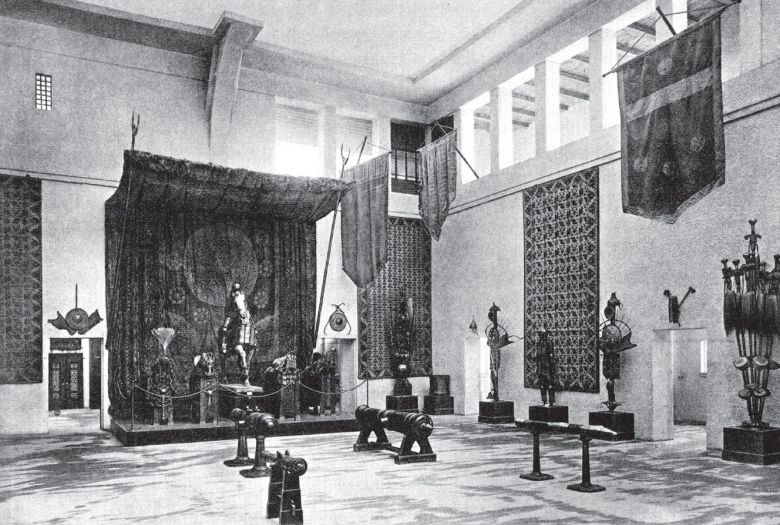

The Ghubar team explores and analyzes pivotal moments in the historiography of Islamic art. The groundbreaking and later criticized exhibition Meisterwerke muhammedanischer Kunst (Masterpieces of Muhammadan Art), which took place in Munich in 1910, showcased over 3,600 artworks from around 250 international collections, significantly expanding the scope of Islamic art by including pieces from non-Arabic-speaking regions of the Muslim world — a step toward diversifying the field.

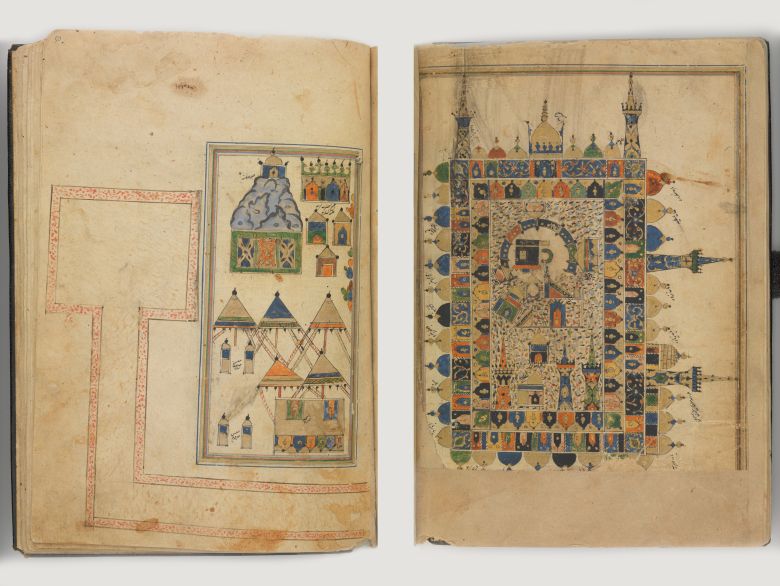

Codicology, the study of manuscripts with a focus on their historical context and cultural aspects, is a key part of Ghubar’s agenda. It helps trace the origins, production, and role of manuscripts in the transmission of knowledge and culture. The Futuh al-Haramayn consists of a poetic description of the two holy Muslim sites of Mecca and Medina. It was intended to explain the rituals of the pilgrimage (hajj) all Muslims must complete once during their lifetime.

The lecture series “A New Narrative: Art and Architecture in Safavid Isfahan” was organized November 13, 2023 by the Ghubar research group in collaboration with the Humanities Support Institute. Lectures by Negar Habibi, art historian and lecturer in the history of Iranian and Islamic art at University of Geneva, Nastaran Nejati (University of Art, Tehran), and Mojdeh Mokhlesi (University of Art, Tehran) addressed topics such as the subtle connections between painters, courtiers, and Western artworks housed in locations such as the royal treasury of Shah Soleiman’s court; the manifestation of the concept of power in the architecture of the Safavid statehouse; and a fresh perspective on the miniature painter Reza Abbasi (ca. 1570-1635) through the lens of his inscriptions and numerical annotations.

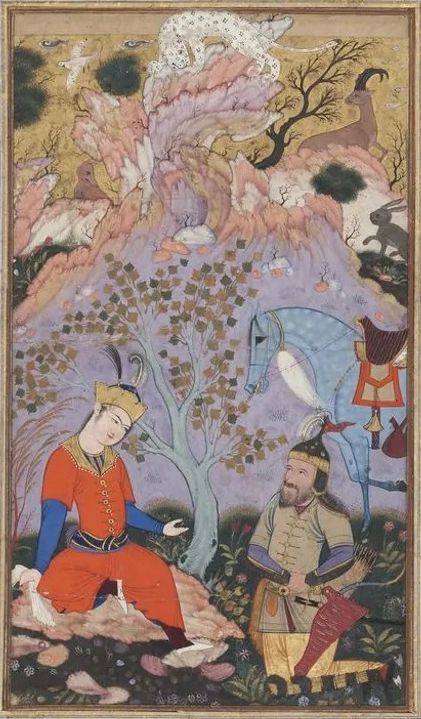

The Ghubar research group organized the lecture series “The Idea of the Just Ruler in Persianate Art and Material Culture” on April 23–24, 2024, in Iran, in a hybrid format accommodating both online and in-person participation. This event brought together eight notable Iranian and international scholars, including Negar Habibi (University of Geneva), Azadeh Latifkar (University of Art, Tehran), Elena Paskaleva (Leiden University), Amir Maziar (University of Art, Tehran), Shervin Farridnejad (University of Hamburg), Mélisande Bizoirre (Independant Scholar, Paris), Ali Boozari (University of Art, Tehran), Mira Xenia Schwerda (University of Edinburgh), and Hamid Reza Ghelichkhani (Independant scholar), who presented their research in Persian and English. The discussions built upon Volume 5 of the Manazir Journal, edited by Negar Habibi, which focused on the enduring concept of the Just Ruler in Persianate political and cultural history. This idea, emphasizing a sovereign who balanced spiritual devotion with the administration of justice and prosperity, deeply influenced Iranian kingship and its material culture, as reflected in the construction of palaces, gardens, and cities that symbolized order and beneficence.

The event also explored the broader impact of Persianate artistic and intellectual traditions across regions extending from Central Asia to Eastern Anatolia between the 14th and 19th centuries. Through various media—including illuminated manuscripts, monumental architecture, and modern photography—the series examined how rulers invoked and adapted the ideals of just kingship to assert their legitimacy and authority. By hosting this event, the Ghubar Team highlighted how the concept of the Just Ruler continues to resonate, bridging historical ideals with contemporary interpretations of governance and cultural identity.

For further details, refer to the abstract of Manazir Journal’s Volume 5: The Idea of the Just Ruler in Persianate Art and Material Culture, edited by Negar Habibi.

In her lecuture “Samarqand’s Congregational Mosque of Bibi Khanum as a Representation of Timurid Legitimacy and Rulership”, Elena Paskaleva examined how the Bibi Khanum Congregational Mosque, the largest Timurid monument in Samarqand, was commissioned by Timur in 1399 to symbolize his ambition to surpass the architectural achievements of earlier Islamic dynasties. By emulating and exceeding the grandeur of Ilkhanid capitals like Tabriz and Sultaniyya, Timur reinforced the Timurid dynasty’s political legitimacy as the just successors to Chinggis Khan.

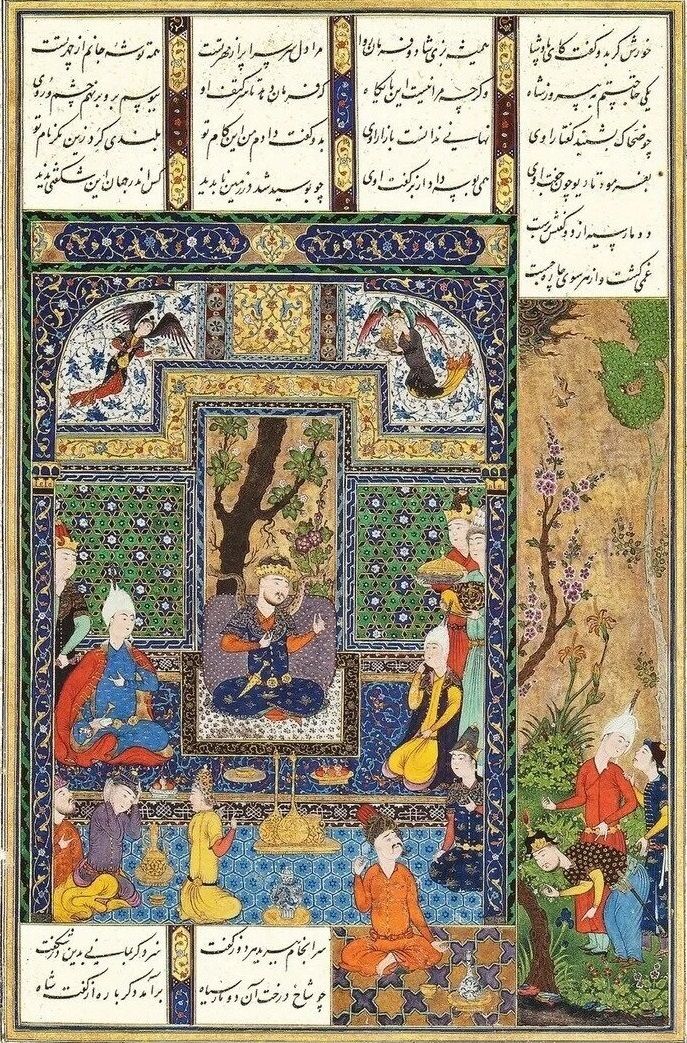

In their lecture “The Sacred King in the Shah Tahmasp Shahnama, The Tree as a Generative Idea of the Idea of Kingship”, Negar Habibi and Shervin Farridnejad explored the pre-Islamic Zoroastrian concept of “royal divine glory” (farr) as visualized in 16th-century Safavid manuscript illustrations, particularly the Shahnama-yi Shahi. They delved into illustrations of Zahhak’s story to examine how artists depicted the divinity and dignity of Iranian kings while distinguishing between profane and Shiite iconographies.

In her lecture “De la poudre aux yeux, Les stratégies artistiques de légitimation des souverains d’Iran (1722-1750)”, Mélisande Bizoirre argued how Nader Shah and his successors, rising from humble origins and ending the prestigious Safavid dynasty’s rule in Iran, faced significant challenges in legitimizing their authority. While military victories played a role, art, architecture, and material culture were more critical tools in their quest for legitimacy. Through palaces, ceremonial displays, grand structures, inscriptions, opulence, and the adoption of Safavid customs, they conveyed regal status and authority.

1 While there is no single definition of “Islamic art,” there is a consensus that the term, unlike “Christian art” or “Jewish art,” does not refer exclusively to the art of a religion. Rather, it carries broader cultural connotations, encompassing various forms of art and architecture produced in the Muslim world, both religious and nonreligious.

2 For instance, see Alois Riegl and David Castriota, Problems of Style: Foundations for a History of Ornament. Princeton (N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1992) and Ernst Kühnel, The Arabesque: Meaning and Transformation of an Ornament (Graz: Akademische Druck- und Verlagsanstalt, 1949).

3 For an in-depth critique of these early approaches, see Gülru Necipoğlu and Mohammad Al-Asad, Topkapı Scroll: Geometry and Ornament in Islamic Architecture: Topkapı Palace Library MS H. 1956 (Santa Monica, CA: Getty Center for the History of Art and the Humanities, 1995).

4 For further reading, see Andrea Lermer and Avinoam Shalem, eds., After One Hundred Years: The 1910 Exhibition “Meisterwerke muhammedanischer Kunst” Reconsidered (Brill, 2010).

5 For instance, see Ashley Miller, Decolonizing Islamic Art in Africa: New Approaches to Muslim Expressive Cultures (Intellect Books, 2024) and Finbarr Barry Flood and Beate Fricke, Tales Things Tell: Material Histories of Early Globalisms (Princeton University Press, 2023).

Niloufar Lari, Salimeh Hosseini, Negar Shariatnia, Azadeh Latifkar, Nastaran Nejati, “Ghubar’s Approach to Islamic Art Historiography,” in mohit.art NOTES #14 (December 2024/January 2025 ); published on www.mohit.art, December 3, 2024.