Content

Notes #14

In the heart of the northern hemisphere, where the western expanses of Asia unfold, lies a region of cultural convergence. This territory, a mosaic of varied landscapes, is defined by distinct geographical features: the Darband mountains and the River Jaxartes in the north, the northern reaches of the Himalayas to the east, the calm southern shores of the Sea of Oman and the Persian Gulf, and the Euphrates River and Eastern Anatolia to the west.

This expansive territory embraces a complex amalgamation of countries, including Iran, Azerbaijan, Armenia, Georgia, Dagestan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan, the sheikhdoms of southern Oman and the southern Persian Gulf, Iraq, and eastern Turkey. Each plays an important role in crafting a tapestry that is as diverse as it is interconnected. Spanning various geographical realms, it narrates a tale of unity amid linguistic and ethnic diversity. The Nowruz festival,1 a celebration that transcends borders, serves as a vibrant testament to this millennia-old culture, embodying the spirit and unity of the regions collectively designated “Nowruz Land.”

Nowruzgan is a laboratory devoted to the study of the cultures of the Persianate world. It engages comprehensively with the cultural expressions of this vast region — ranging from art and architecture to literature, language, and customs — encompassing both material and non-material cultures. It has a special concern for exploring and elucidating connections: linking texts and documents to land and geography; bridging different cultural manifestations; connecting disparate historical evidence; tracing the relationships between concepts, terms, and words; and examining the ties among the various subcultures of the Persianate world, both in historical and contemporary contexts. The geographical scope of Nowruzgan extends to the entire Persianate sphere, broadly defined as regions where Persian/Dari/Tajik, or its closely related languages, are or have been spoken. Chronologically, Nowruzgan’s inquiry is unrestricted, encompassing periods from prehistory to the present.

Alongside research, one of Nowruzgan’s primary concerns and ongoing activities is education. Nowruzgan School, for example, serves as an educational hub focused on teaching, promoting, and advancing knowledge in the fields of humanities, culture, arts studies, environment, and water management in the Persian-speaking world, offered through courses, lectures, symposia, and roundtable discussions.

One of the main barriers to the dissemination and in-depth exploration of diverse fields of knowledge — particularly in the humanities and cultural studies — is the existence of political borders. These arbitrary boundaries have fragmented real and historical-cultural communities, leading to the monopolization and exclusivity of topics and resources. This situation has resulted in the isolation of research and researchers from one another. Nowruzgan aims to eliminate these borders in humanities and cultural studies by emphasizing shared linguistic, ritualistic, and cultural connections to imbue thought and research with a deeper cultural resonance.

Nowruzgan’s overarching policy supports the free dissemination of information and knowledge. Therefore, the Nowruzgan School focuses primarily on online and virtual education. To this end, the school has developed an exclusive platform for hosting various online events. This platform supports lectures, symposia, roundtables, discussion sessions, short-term open classes, and various online and recorded virtual educational programs, also in collaboration with other organizations and initiatives. The sessions conducted on this platform are recorded and made freely available in the Nowruzgan School section of “Chaharrah,” Nowruzgan’s internet television network, accessible at www.chaharrah.tv.

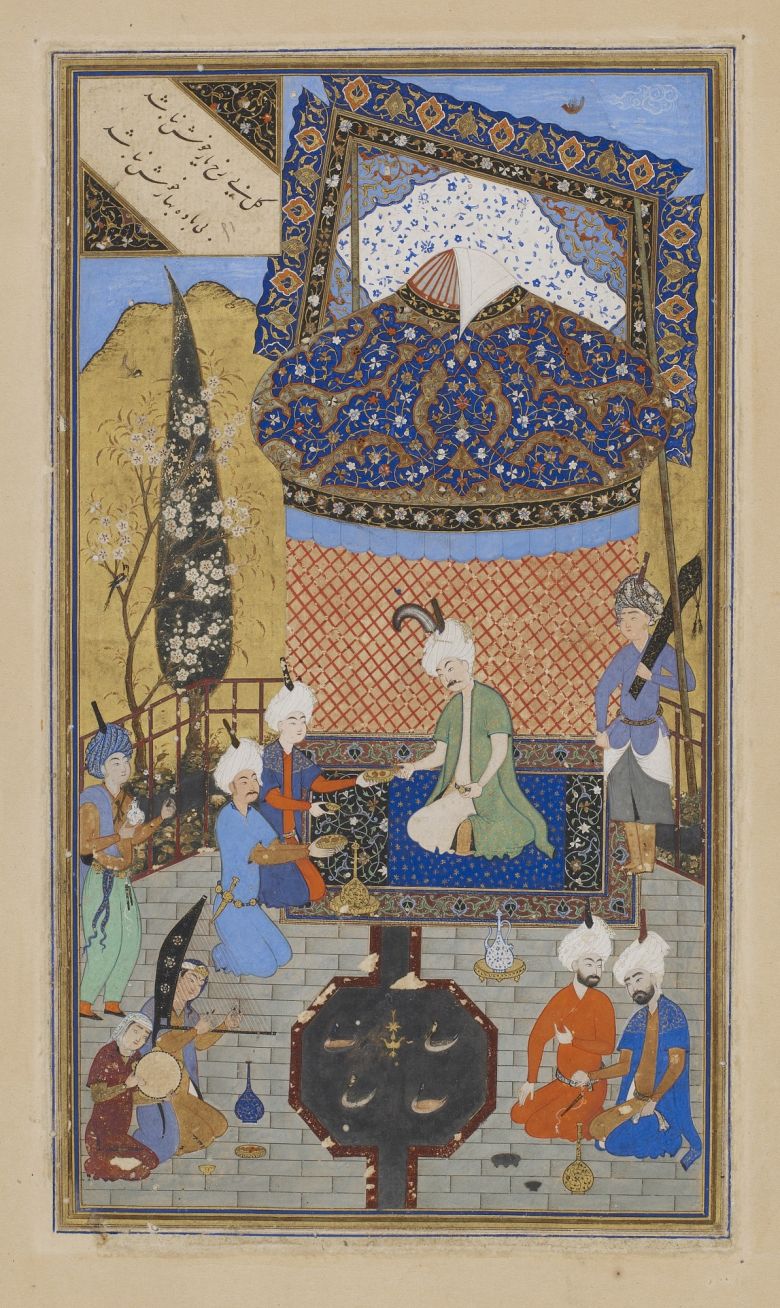

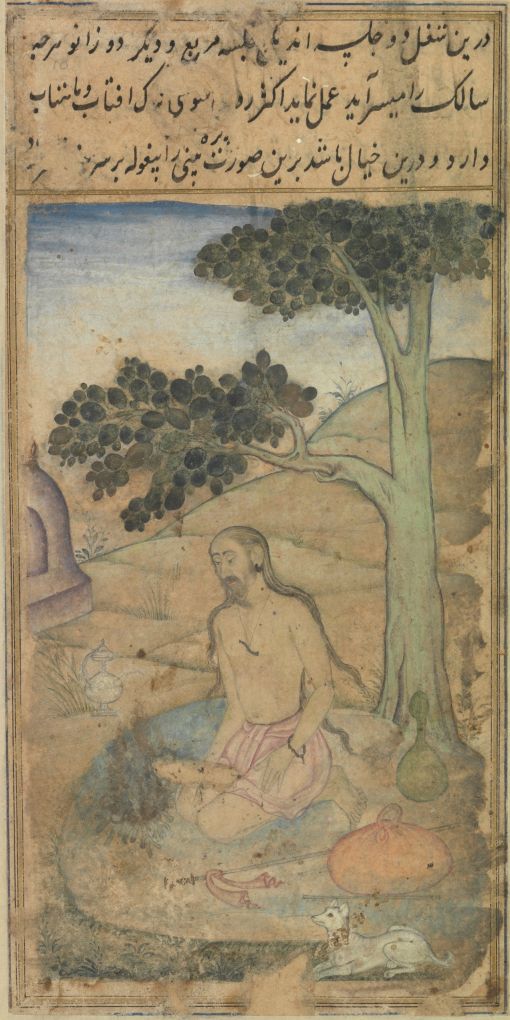

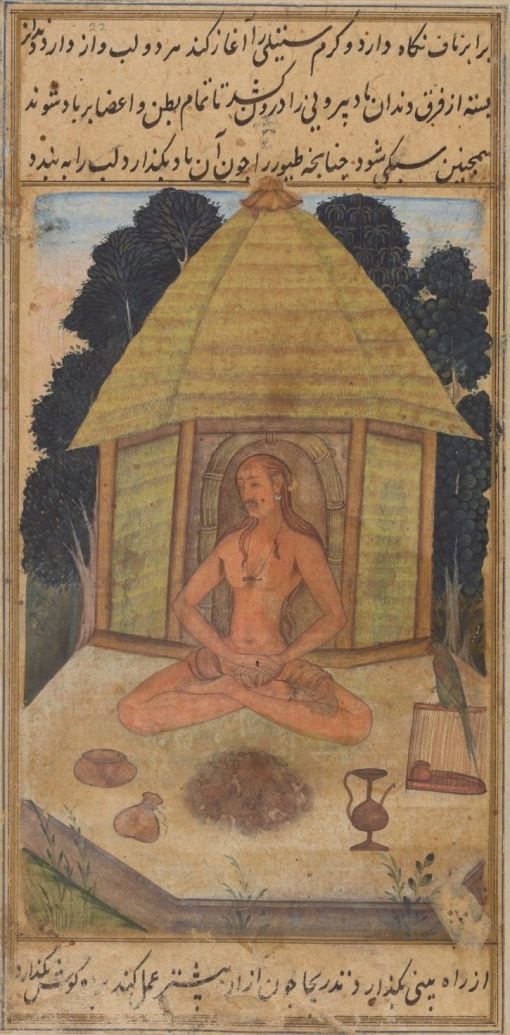

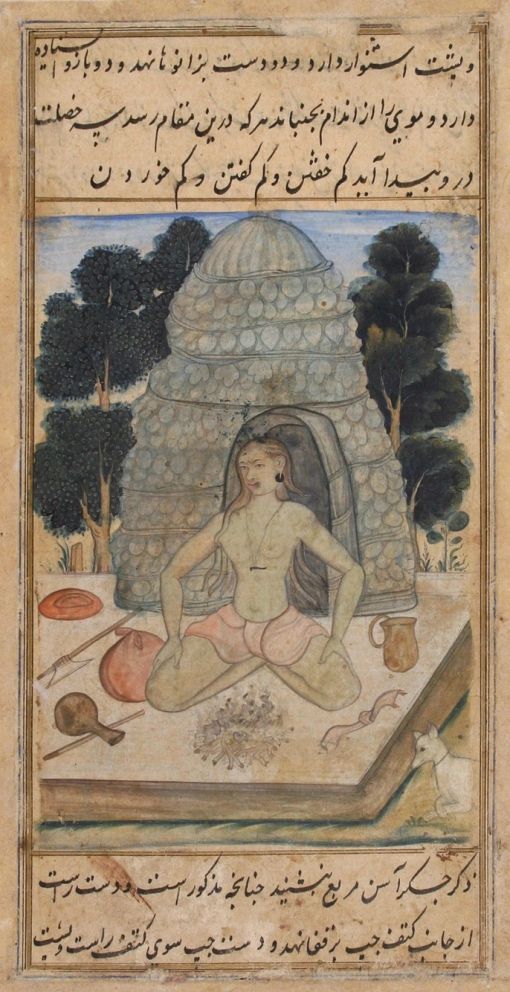

The concept of “Nowruz Land” represents a vast geographical region where diverse landscapes and a shared cultural identity converge, uniting its people through common traditions, languages, and the celebration of Nowruz. Nowruzgan explores the art of this Persianate world by examining its diverse cultural expressions, connecting historical and contemporary manifestations, and linking art, language, and geography within this richly interconnected region.

The goal of Nowruzgan School is to make high-quality educational content accessible to all enthusiasts, including those with limited access to the internet (through registered courses). Its long-term vision is to establish a comprehensive repository of educational courses focused on the culture and arts of the Persianate world.

In his exploration of the Qajar era’s musical landscape, Ahmad Sadri delves into the pivotal question of artists’ social roles during Iran’s Constitutional Era and their impact on the evolution of Iranian musical forms.

Launched in October 2021 as part of Nowruzgan, the project Ketabkhaneh: Nowruz Land Cultural Archive preserves and publishes archives spanning historical and contemporary periods, including photographs, maps, manuscripts, historical publications and modern visual and textual documents, to reflect the region’s evolving cultures. There are currently around 8,000 documents in two archives, which can be accessed at ketabkhaneh.org, aiming to continue to grow and provide a gateway to the diverse historical and cultural narratives of the region.

Adel Farhangi, an architect, researcher, and photographer, has contributed a vast photo archive of Iranian architectural sites to Nowruzgan’s digital archive. Renowned for his dedication to preserving and restoring historical buildings, Farhangi has been actively involved in national restoration projects for many years. His extensive archive is accessible via ketabkhaneh.org.

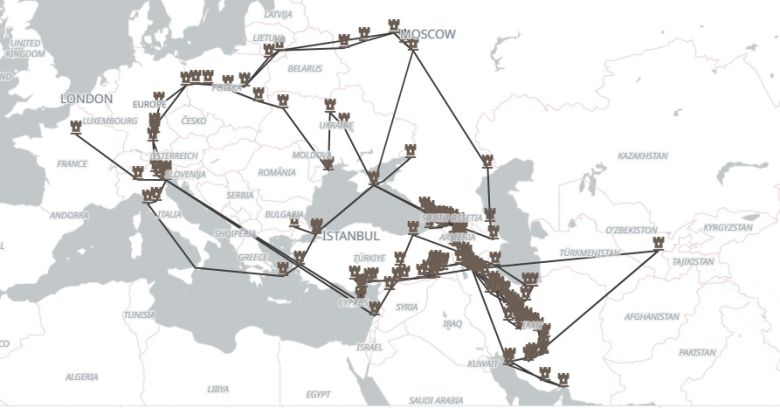

Safarnameh is a project by Nowruzgan, launched in February 2022, that compiles approximately 1,500 entries from multiple sources. Travelogues provide deep insights into history, spanning the humanities, natural sciences, and everyday life – often detailing aspects missing from other contemporary records. The project aims to map and connect this wealth of information, contextualizing each piece of data. A visual feature superimposes the historical routes of travelers on a modern map of the world, linking past journeys to contemporary locations. Accessible at nowruzgan.com.

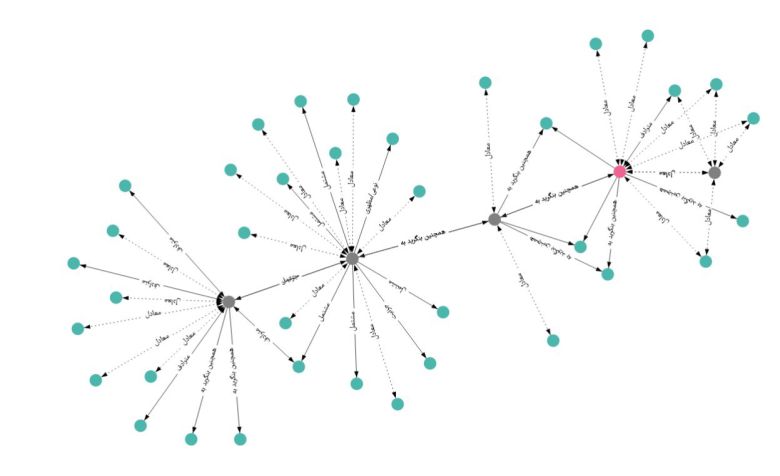

Vazhgar, a project developed by Nowruzgan, is a multilingual online dictionary focused on architecture, art, and visual culture. Available in Persian, English, Arabic, Italian, French, German, and Spanish, it serves as a comprehensive terminological resource for fields like architecture, urban history, art history, conservation, archaeology, and cultural studies. Each entry includes the word’s etymology (for most languages), translations in multiple languages with sources, a definition in Persian, an example sentence in Persian, and a semantic diagram illustrating the term’s relationships. Additionally, Persian terms in Vazhgar are connected to other Nowruzgan projects and Persian corpora, allowing for in-depth semantic analysis.

arabesque

Etymology:

1786, “Moorish or Arabic ornamental design,” from French arabesque (16c.), from Italian arabesco, from Arabo “Arab” (see Arab), with reference to Moorish architecture. In reference to an ornamented theme or passage in piano music it is attested by 1853, originally the title given in 1839 by Robert Schumann to one of his piano pieces (“Arabeske in C major”). As a ballet pose, first attested 1830.

The name arabesque applied to the flowing ornament of Moorish invention is exactly suited to express those graceful lines which are their counterpart in the art of dancing. [“A Manual of the Theory and Practice of Classical Theatrical Dancing,” 1922].

Meaning and context:

A word derived from “Arab” in European languages, in the general sense of “Arab-like” or specifically “Arabic pattern,” which was used in the West to generally describe all kinds of motifs and images borrowed from Sasanian, Byzantine, and Islamic art; motifs and images whose history dates back to much more distant times and whose diversity and dispersion, as recent research has shown, were not limited to the three centers mentioned above, but rather extended from northwestern Europe to central and southwestern Asia. In any case, the word arabesque in Western languages includes all kinds of plant images – vines, palms, artichokes – with intertwined stems and leaves and sometimes flowers, and circular, parallel and symmetrical lines that repeatedly intersect or run one after the other; and also straight geometric shapes and angular knots. Finally, all of this is mixed with images of birds, animals and humans. In Persian, however, the elements and components of these images are distinguished from each other and have found separate names that do not all appear in European languages, such as: Islamic scroll, elephant trunk, snake, dragon’s mouth, khatai and Islamic khatai, changgowra, butehjaqeh, and others.

1 Nowruz (also spelled Norooz or Nawruz) is the Persian New Year, celebrated at the exact moment of the vernal equinox, marking the first day of spring in the northern hemisphere. It typically falls on or around March 20 or 21.

Mohammad Gholam’ali Fallah, “A Laboratory for the Study of the Persianate World,” in mohit.art NOTES #14 (December 2024/January 2025); published on www.mohit.art, December 3, 2024.